CREATING A PLACE TO FEEL AT HOME

The Christian church and social control in A township in Lusaka, Zambia, in the early 1970s

Wim van Binsbergen

|

CREATING A PLACE TO FEEL AT HOME The Christian church and social control in A township in Lusaka, Zambia, in the early 1970s Wim van Binsbergen |

|

1. Introduction[i]

After a spate of studies concentrating on urbanisation and the formation of modern African towns, the study of African urbanism gained impetus in the 1970s: researchers sought to explore the patterns of urban social, political and religious organisation, life-styles and class formation as manifestations of a way of life that was increasingly following a dynamic of its own and for whose sociological treatment it was no longer meaningful to take the rural areas as main reference and point of departure. In Zambia, this development had already been foreshadowed by the famous Copperbelt studies of the Rhodes-Livingstone Institute, most field-work for which went back to the first half of the 1950s. Brilliant and influential as these early studies have been,[ii] they somewhat underrated the continued relevance of rural inputs for an understanding of contemporary urban African society; besides, they had two major blind spots

(a) the study of the domestic domain of urban kinship and family life (however, cf. Epstein 1981), and

(b) the study of that dominant form of voluntary associations in South Central African towns: Christian churches.

Thus while in other parts of Africa, in the wake of Sundkler’s pioneer study (1948, 1961), the study of Christianity and particularly of independent churches became a major topic in Africanist research including urban studies, in Zambia the sociological study of modern religious organisations and their impact upon the vastly expanding urban society had to wait till the end of the 1960s (with Stefaniszyn 1962 as an early, minor exception). David Wiley’s doctoral research (1971) was to be the first of a series of interesting explorations[iii] in which however sociological concerns still tended to be blended with research priorities derived from such fields as symbolic anthropology, church history, pastoral theology, etc.

Initially my own research in urban Zambia focused on the classification of churches, their formal organisational structures and inter-church interactions, as an exercise in the sociology of organisations more than as an exploration of the emerging urban society as a whole. In later years I was increasingly drawn into an analysis of the urban life, the history and contemporary rural-urban relations of an ethnic minority (the Nkoya) whose pursuit of autochthonous, neo-traditional forms of religion rather outweighed their participation in Christian churches. However, somewhere between these two phases I occupied myself for two years (1972-73) with part-time field-work on the interaction between precisely the two relatively unexplored topics mentioned above: the contribution of formal (Christian) religious organisation and of rural-derived patterns of kin intervention and support, to the emergent patterns of social control that informed family and marital life in Lusaka.[iv]

The paper touches upon a form of interreligious dialogue which goes on continuously in contemporary Africa: that between historic forms of African religiosity and world-view, on the one hand, and on the other hand world religions such as Christianity and Islam, introduced from outside the African continent but since solidly rooted there, and ramifying into a great variety of localising, African forms. More importantly, my argument seeks to illuminate one of the social contexts in which such dialogue, and other forms of intra-religious dialogue, will be particularly put to the test: the African urban environment, which has gained dominance in the course of the twentieth century and which will be crucial in determining the patterns of African life and religiosity in the twenty-first century. In Africa and elsewhere, towns are the laboratories where, out of social, cultural and religious forms converging there on a world-wide basis, new answers are constantly formulated and tested out for the moral and symbolic predicaments of people uprooted from once closely-knit and meaningful communities (cf. Shorter 1991; ter Haar 1991). The present paper suggests that in this process of re-orientation and re-anchorage, organised religion may yet have a crucial role to play.

The present paper pretends no more than to indicate certain descriptive and analytical themes as might be clarified by such a project. For this purpose, I shall follow a line of argument that has proved useful and illuminating in the context of Zambian urban studies.[v] I shall start out with a detailed presentation of relatively unprocessed material focusing on just one urban protagonist. Such data retain something of the real life of urban Zambia, and allow us to become familiar with at least one of its inhabitants, while at the same time structural relations and contradictions can be seen at work which, despite their unique bearing on this particular case and individual, yet can be shown — in the subsequent discussion and conclusion — to be fairly representative for the Zambian urban structure as a whole.

Significant changes have occurred in that urban setting since the date of the field-work in the early 1970s. The United National Independence Party, then the ruling party and in control of much of the social process especially in the squatter areas where formal state structures were lacking, has retreated to a minority position. The hardening of class lines and the decline of the Zambian economy over much of the 1970s and 1980s has had a tightening effect on urban reception structures of migrants and on urban relations in general; awareness of AIDS has translated these attitudes to the sexual sphere, where far greater reticence can now be observed. Yet with these correctives, the interrelations between church and urban social control as explored in the present paper would appear to be far from obsolete.

2. Continuity and transformation in the sociology of urban Zambia

In this exploration, our leading question will be: what is the stuff that Zambian urban society is made of? In this part of the African continent, towns (as structurally and functionally complex and heterogeneous large-scale concentrations of human habitation) only came into being during the colonial period. Towards the end of that period the state’s initial urban influx control (cf. Heisler 1974) waned, and it ceased to exist entirely when Zambia attained Independence in 1964. How did the several million of Zambian urbanites (for many of whom their urban existence remained sandwiched between a rural youth and an equally rural retirement phase) cope with the problem of creating and maintaining a more or less viable pattern of urban life? For the purpose of our present discussion I should like to take the obvious economic determinants of urban life (in terms of labour migration, rural-urban flows of cash and labour power, and the organisation of the urban, national and world economy) for granted, and concentrate on the more strictly sociological dimensions of urban life: patterns of social organisation that give rise to broad social categories, whose more or less enduring interrelations — both formal and informal, and against the background of values and collective representations of various origins and in a general state of flux, accommodation and change — pattern the specific interactions between individual townsmen (heads of households as well as their co-resident dependants). In this context, where most urbanites can still be considered to be relatively recent migrants from rural areas, one would expect to see at least the following main factors of urban social structure at work:

(a) Urban transformations of rural patterns of social relations in the domestic, kinship and ethnic sphere.

(b) Urban transformations of rural-based forms of formal, ‘modern’ organisations, such as represented by e.g. churches, political parties and other voluntary associations in which contemporary rural people used to participate before migrating to town.

(c) Specifically urban-based formal, ‘modern’ voluntary organisations — which may or may not be conterminous with their rural counterparts. If so, these organisations may represent a welcome continuity between rural and urban life — e.g. urban migrants finding an urban reception structure in an urban congregation of a church they had already joined when still ‘back home’. However, when such continuity is absent, urban migrants may become specifically involved in new or different urban-based formal organisations as a hallmark of their becoming urbanites, allowing them to define themselves, in terms of life-style, political and economic goals and incentives, values and perceptions, in their new, urban social space and to enter into effective urban social relationships whose referents are no longer largely derived from a rural origin.

(d) Emanating from the political and administrative centre of the post-colonial state there are formal organisations such as the municipal administration, the police and the judiciary (in the specific form of urban courts) in which the new urbanites may only peripherally and occasionally participate, as clients, but which yet to a considerable extent set the confines for the emerging patterns of urban relationships the inhabitants of the new and expanding townships engage in.

One would expect that out of the interplay between these and similar factors, new and specifically urban patterns of social relations have emerged in town, which on the one hand cater for the more intimate, ‘informal’ spheres of domestic life, neighbourly relations and the structuring of relatively small-scale structural niches (wards, compounds, sections, suburbs), and on the other hand link these micro phenomena of the urban scene to the broad organisational and political patterns of modern Zambian society at large.

Here the fundamental theoretical and descriptive puzzle revolves on the relative importance of continuity and transformation. Already since Mitchell’s masterly study of The Kalela Dance on the Zambian Copperbelt (1956) we have known that rural cultural and social-organisational elements are never introduced stock, lock and barrel into the urban scene. Particularly patterns of ethnic perception and inter-ethnic interaction in the urban environment do no emulate rural models but take on totally new forms, largely determined by the one-stranded and selective, individual-centred nature of urban social (network) contacts within an overall framework of capitalist relations of production and consumption. Likewise (precisely because of the constraints of urban housing and differential individual insertion in the urban economy and status system) kinship and family life in town can only to a limited extent be expected to follow the pattern of village life in which the urban migrants were, nonetheless, raised and to which they will often return upon retirement. On the ideological level, rural notions of power and causation, supernatural intervention, evil and healing could be expected to lose much of their applicability when the people who carry these collective representations across the urban boundaries: into a sphere of social life where the effects of formal bureaucratic power and authority, and the scientific principles of causation underlying modern technology and health care, loom rather larger than they tend to do in even contemporary African villages.

The emphasis on urban transformation, and the very term urbanism, would already seem to imply that modern African, including Zambian, urban life has taken on characteristics sui generis, which no really significant reference any more to rural social-structural and ideological inputs.

Yet urbanites’ continued interaction with their rural kin, and their much-documented capability of resuming their rural existence, suggest a very considerable continuity between town and country, — as if the transformation of rural forms in the course of their urban existence is far from irreversible, and retains detectable traces of the rural input. Or, again, as if between town and country in South Central Africa a considerable common ground — a deep structure? — of social forms and ideology has evolved, elements and potentialities of which may be selectively and situationally stressed according to whether one finds oneself in town or in the village, without denying the considerable underlying unity and continuity.

The determinants of the dialectics I am hinting at here, have rather eluded scholarly analysis. So far we have only just begun to spell out the rules of selection and transformation that appear to govern the interplay between the urban migrants’ rural input, formal voluntary organisations, and the state, as the three major sociological determinants of urban social relations (in addition, again, to economic factors). Admittedly, scholarship has addressed the differential recourse to either rural or urban mystical explanations of misfortune (Parkin 1975: 24-7 and references cited there; again the pioneering work was done by Mitchell, 1965), and what applies there might be construed to apply to other aspects of the urban/rural dynamics as well. Parkin casts the initial findings on this point in the form of the following hypothesis:

‘The more alienated a migrant group is from the political and economic control of the city in which it works (...), the more likely it is, when using mystical explanations of misfortunes, to ascribe them to rural rather than urban causative agents. This must assume that the group retains some rural interests and that at least some of its members circulate between town and country. The corollary would be that the politically dominant host group ‘discovers’ a larger proportion of urban causes or simply makes little distinction between them and rural ones. (...) All this rests on the assumption that townsmen conceptualise behaviour and values as being different between town and country.’ (Parkin 1975: 27).

Indeed,

the relative amount of transformation, and of continuity, that

individual actors display in their own structuring of their urban

relationships, is likely to be related to the security or

insecurity of their foothold in the urban power structure and

economy, their urban or rural status aspirations, their closeness

or distance vis-à-vis to the urban and national political

centre, and their relations with others (migrants, urbanites and

villagers) from the same home area but in different phases of

urban adaptation than themselves. But even so one might be

surprised at the extent of rural continuity one finds even among

the relatively wealthy, politically successful town dwellers,

— even if they have underpinned their commitment to modern

life by an ideological conversion to a world religion such as

Christianity. The approach as summarised by Parkin is based on

far too rigid a distinction between urban and rural, not only as

analytical tools but also as cognitive projections into the

participants’ minds. It fails to appreciate the situational

nature of this distinction, the capacity for urban and rural

traits to remain dormant or latent in some situations but to

spring forth in others, all involving the same actors. It

underplays ideological, symbolic and cosmological implications

which cannot be totally reduced to epiphenomena of political and

economic factors at work in town; nor does it appreciate the

importance of such formal organisations (e.g. churches) through

which these ideological dimension tend to be structured and

expressed. It fails to appreciate that sorcery is an idiom not

only of power and success but also of morally and hence of social

control. A minor point finally: with reference to Lusaka, the

concept of a dominant host group does not apply, for since the

creation of European farms in this area in the first decade of

this century the local ethnic groups (Sala, Lenje, Soli) have

been eclipsed by migrants from other more distant groups, to such

an extent that (after a short episode when Bemba was used) the

Eastern-Province Chewa language, simplified into

‘Nyanja’, has become the town’s

lingua franca.

In other words, there is plenty of reason for further exploration into this fascinating topic.

3. A glimpse of Lusaka life

In order to introduce these various themes in the urban sociology of modern Zambia, I have selected, from among my Lusaka field data, a long monologue, by ‘Mrs. Evelyn Phiri’.[vi] This complex statement has not been picked for the attractiveness of Mrs. Phiri’s character, her exemplary nature as a Christian, or the consistency with which she tells her tale. Yet her personality, the irresistibly contradictory way in which she presents her case, along with her frankness and irascibility, may turn out to have a beauty of their own, recognisable for us across cultural and linguistic divides.

Methodologically, the approach cannot be called anything but exploratory: a close-reading of the words of only one — albeit loquacious — informant. On the surface, this long monologue would appear to throw light upon the urban life of only one, particularly well-to-do, lady with political and social aspirations way beyond those of ordinary Lusaka townsmen and townswomen. Mrs. Phiri should be seen as combining extreme ends of a whole bundle of ranges and continua. And this applies to many aspects of her situation, such as: income; housing situation (living in a spacious and solid house owned by her and her husband, in a brand-new suburb where social relations are still in the first stages of crystallising; personal political power; status incongruence as compared to her husband (cf. Glazer Schuster 1979); age; perhaps even her massive capability to hide the real facts of her life behind idealised statements of rules and principles. This lack of representativeness should not deter us at the present stage of our exploration. In certain other respects Mrs. Phiri’s situation is fairly representative. At the time of the research, shortly after the creation of the one-party state, many Lusaka townships went through the final throes of accommodation between UNIP and pre-existing rival political parties, but Kapemperere had been UNIP-dominated from the beginning; moreover it largely housed urban migrants from Eastern Province. As a UNIP leader from the east Mrs. Phiri is very well at home here. Similarly, her position as a member of a well-established church body (the Roman Catholic church) is far from exceptional.[vii]

In this context it is even largely immaterial whether Mrs. Phiri’s account of her religious and political leadership and of her struggles with her husband, son, affines, neighbours and political rivals presents us with the whole truth and nothing but the truth; of course it does not — as other data at my disposal clearly indicate. What is important is that, even in her partially a-typical social position, she invokes collective representations and structural features of contemporary Zambian life which both participant observation and quantitative survey data show to have a very wide applicability, and which even her attempts to impress her audience do not seem to have distorted beyond recognition.

4. Mrs. Evelyn Phiri’s monologue

(1) ‘I can tell you plenty about church life in this township, since I am the leader of Catholic Action here.[viii] This is a very new township, you can see that the people are still moving in, so our Action here has not yet started to function properly; we are waiting for a meeting which is to be held next week.

(2) ‘As far as Action is concerned, our main work is to visit and help people. Throughout Kapemperere there are leaders of Action: each section[ix] has its own leader. We have a regular weekly schedule for our activities: on Tuesdays we visit the people, and on Wednesdays we meet as a committee in order to submit reports and findings.

(3) ‘Among the people we visit as Action are Christians who have left the Roman Catholic Church for various reasons, and those who want to join the church.

(4) ‘At times, when we are invited to do so, we combine our activities with the Action groups of other churches: A.M.E.., Anglican and Reformed.[x] The leaders of the Action groups of these other churches live nearby in Kapemperere: Mrs. Ndhlovu for the Anglicans, and Mrs. Bread for the Reformed Church.

(5) ‘When a woman does not have a man to support her, Action gives her food and clothes. When a woman is ill she is assisted to keep her home clean, e.g. women come sweeping and drawing water for her. This applies to all people, regardless of whether they are Christians or not. When a man is in trouble, his wife will come and ask my husband to help him. I will cook food for her.

(6) ‘When a Christian backslides, Action tends to visit him or her continuously until he returns to the ways of the church. Some women are not allowed to go to church because their husbands are not Christians or belong to other denominations. In that case a meeting is held with the husband to persuade him to release [sic] his wife to go to church. This is done by the leaders of Action, even by male members of the church. Both Action and [the] Legion [of Mary] comprise men and women.

(7) ‘Another important activity is that we help people without relatives in town, to arrange funerals. At the time of a funeral, all church people of the township gather together: Reformed, Anglicans and Catholics. If the deceased is a woman, the women must bathe and dress her before she is put into the coffin. In case of a man it is men who do this. If the deceased has left behind any small children, a week is spent at the deceased’s house trying to console them. Prayers are said there and we prepare food for the children. In the past, children left behind by a good Christian used to be helped by Action, e.g. in the way of finding them school places,[xi] and taking care of them in every way. These days this is not done any more.

(8) ‘When a Christian in town wants to go back to his or her home in the rural areas, the church does assist e.g. by giving money. For example, my sister Theresia, who has been an Action member since 1947, was repatriated to Minga, by the church.[xii] She was given K28 when famine struck that area.[xiii] All this was done by the Catholic parish in the name of the church.

(9) ‘Marriage is also a very important field of activity for us. When a young man wants to marry, he approaches the members of Action and tells them which girl he fancies. The members will tell the priest, whom we call Bambo.[xiv] Action notifies the girl’s parents of such marriage arrangements as are proposed by the relatives of the boy.[xv] Subsequently, male members of Action are told to watch the young man so that he does not involve himself in unlawful acts with the girl. If the two young people are ever found out together, Bambo is told and the Christian marriage as planned is cancelled: for the girl might turn out to be pregnant. At the marriage ceremony, the church contributes money and helps the two parties meet expenses. If the girl is already pregnant, the church marriage is cancelled, but of course the two can still marry as outsiders to the church, in the traditional fashion. If this happens, the parents on both sides are excluded from receiving Holy Communion for a year or so.

(10) ‘Both Legion and Action groups spent a lot of time advising and passing judgement on behalf of the church. There is a lot going on in the Church which, if it were revealed to the majority of the church members, would cause great scandal. The Legion and Action try to hush up such matters for the sake of the people concerned and also for the church. For example there are adultery cases that never reach the courts or ordinary members of the church within Kapemperere.

(11) ‘Suppose a man is a Catholic, and he finds his wife in bed with another man who is also a Catholic. Do you think the victim will immediately run off to the Urban Court to buy a summons?[xvi] No, that is not the way of the church. The wronged husband is supposed to call Bambo and the leaders of Legion and Action here in Kapemperere. These people will discuss the case in private, and request the offender not to do it again. The owner of the house [sic] is asked not to bear a grudge against the other man. The matter should end there and friendship should continue as before. That is how we go about these matters in the church.

(12) ‘Something like that happened to myself once. At one time when I was in the family way, Mr. Phiri, my husband, sent me to his home village in order to give birth there. After the delivery I wrote to Mr. Phiri asking him to send baby napkins. But the only thing he ever sent me was a letter telling me that I could go to my own village when I would be feeling well again — adding that he did not love me any more. I was shocked to receive such a letter. But since I have always been a good Christian I decided to go back to my husband despite his abrupt decision to dissolve our marriage. When returning to Lusaka I found that Mr. Phiri was living with another woman. I called in Bambo and leaders of Legion and Action. After much trouble my husband was finally convinced that he was living a life of sin. He got rid of the woman he was keeping and took me back as his wife. Since then we have always lived peacefully as good Christians.

(13) ‘Besides marriage, we also take care of sorcerers. When a member is found out by other church members to possess evil powers of sorcery, he is approached by the leaders of the Legion and Action, and by the priest. We talk and talk and talk, until he clearly sees that Christianity and practising sorcery do not go together. It is really very difficult for this person, for he tends to believe that if he stops committing sorcery, he will die.[xvii] We ask him to pray often. His medicine is taken away from him and burnt.

(14) ‘You can really believe me: such things are happening time and again. Do not believe those people who say that sorcery does not exist. I have seen it with my own eyes, in Malawi, where my father came from. There was a man who had the power to catch sorcerers.[xviii] He would blow his horn in the four directions of the globe and all sorcerers would come running, bringing to this man all that they used for their evil work: roots, horns, parts of the human body, whatever. The repenting sorcerer would then be given a small cut on the forehead,[xix] and if he would ever practise witchcraft again he would surely die.

(15) ‘I myself have evil spirits (mashabe).[xx] If a person who practises witchcraft comes near me I will know it immediately. My hair stands on end, then, and my whole body behaves in an extraordinary way. If a witch would ever come to my house at night I would at once wake up and confront him outside. When one of my relatives at home is sick or dies I always know without being told, and as a rule I will have told others about it two or three days before word about the death reaches here from home.

(16) ‘No, these evil spirits I have, have no effect on my religious life. Mine do not need any dancing to the sound of drums like many others do. The latter are forbidden by the church. Some people who have evil spirits would instantly be knocked to the ground if they tried to make the sign of a cross. But mine are different.

(17) ‘Sometimes however they give me an enormous physical strength that is very frightening to other people. Let me give you an example.

(18) ‘I have a son who was born in 1947 and who is now working as a shunter on the railways here in Lusaka. He got married to the daughter of one of our neighbours. I arranged their marriage in a Christian way, despite the fact that the parents of the girl are not religious at all.

(19) ‘At one stage my son had to go for three months of training in Kabwe.[xxi]He left his wife in my care. I took the responsibility of feeding and clothing this young woman since my son did not send any money from Kabwe; during this time his wife gave birth, too.

(20) ‘I did all the housework. I cleaned the house and cooked food and washed the plates. My daughter-in-law woke up in the morning, made her bed, ate breakfast and went to her mother nearby. I would call her for lunch and supper. She never bothered to wash up after meals. I did not mind at all because I thought: ‘‘This is just a young girl who is still immature to do housework.’’

(21) ‘When there was only one week left before my son was to return from Kabwe, things were really starting to go bad. One day I sent my daughter Rosemary to go and call her sister-in-law for lunch. My daughter-in-law told Rosemary to go and tell her Mama to stuff her lunch up her private parts instead of bothering her while she was at the house of her own mother. Rosemary came back crying and told me everything. I still did not care. Later on my daughter-in-law came and started shouting at me. She went back to her mother’s house and later all her relatives came to me. Mrs. Tembo, my son’s mother-in-law, wanted to fight with me but I refused, because I was going on a trip to Chipata[xxii] where my brother was taken ill; and besides I felt no need to fight over nothing. However, Mrs. Tembo hit me twice in the face before I lost my temper. I grabbed her and started working on her. I hit her with my head in her stomach, and she fell to the ground. I grabbed her throat and tore her clothes. Six people from Mrs. Tembo’s house (including her old mother, the one who has only one eye) came to her rescue but I beat them all. I used anything that I could lay my hands on, to beat them with. I badly beat my daughter-in-law and hit the grandmother in the face. Mrs. Tembo’s party started breaking all my windows. The police eventually stopped the fight, because the Youth[xxiii] could not do so.

(22) ‘I had not a scratch on me but the others were bleeding from cuts. Mrs. Tembo had a big cut on her forehead.[xxiv]

(23) ‘The matter was later taken up with the Kapemperere branch chairman and section leaders. Mrs. Tembo’s party was found to be wrong and asked to pay for the damage done to my house. I however refused any compensation because I am a Christian and because Mrs. Tembo’s daughter is married to my son.

(24) ‘The church leaders did not bother with this case at all. They were all convinced that I was not to blame for the conflict, but had merely been defending myself.

(25) ‘However, Mrs. Tembo’s party came together and decided they should summon me to court for the injuries I had inflicted upon them. When the summons came I showed it to the branch chairman who called Mrs. Tembo and told her she had done wrong to summon me to court since it was clearly she who was in the wrong and not me!

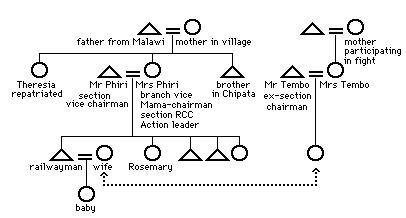

Figure 1. The case of Mrs.

Phiri, Kapemperere township.

(26) ‘At the court I was acquitted, and Mrs. Tembo was very much blamed for the irresponsible way she had handled the situation. We both had to pay K3 to the court.

(27) ‘From then on the hatred between us has persisted, at least from Mrs. Tembo’s side. Our husbands do talk to each other but we women, we do not. In the past I used to buy sugar, meat and mealie-meal for Mrs. Tembo.[xxv] Not that she ever did anything in return... But now every form of friendship is cut.

(28) ‘When my son returned from Kabwe I told him everything that had happened. He went to his wife’s parents and there he was made to eat food mixed with medicine. This medicine was given to him so that he should only love his wife and her relatives, and would not care any more for his own relatives. From that day my son would have nothing to do with us, his parents, nor with his younger brothers and sisters, but he continuously assists his wife’s relatives.

(29) ‘I am not worried about this because I do have money and can afford to educate my children without the help of their elder brother. I buy second-hand clothes from town, from expatriates who sell everything as they leave the country. These clothes I sell again here in the township. In this way I make a lot of money, believe me! Every month’s end I am left with K200 or more. I give some of this money to Mr. Phiri so that he can bank it. Some I put into the bank myself, and the remainder I use to buy more second-hand clothes. You have seen my small shop next to the house, where I sell groceries. Now I want to open a larger grocery within Kapemperere.

(30) ‘The other reason why I am not worried about my son’s behaviour is that my mother does have the medicine to win him back. When the old lady comes to visit here from home she will bring the medicine with her. This medicine she shall give to her grandson, pretending that it is for good luck: that it will make him get promoted or be loved by anyone at his place of work. She will just put it in his tea or his porridge.[xxvi] After my son will have taken this medicine, he will soon realise that he has been neglecting his parents because of his wife. In this way he will start assisting his parents and forget about his wife’s relatives and even perhaps finally divorce his wife. Then she will have what has been coming to her anyway!

(31) ‘Such an ungrateful hussy! As if I am not always helping many people, wherever they come from. There are always people coming to my home, seeking help or asking for something. All right, many people who come here just want to buy from my small grocery, and from them I ask money, of course. But there are still many others for whom I do many things just free of charge.

(32) ‘For instance, there was this woman who came all the way from Kasama[xxvii]in order to see some specialists at University Teaching Hospital. She was very ill. She was staying with her sister[xxviii] who lives next door to me. The husband of the woman from Kasama never came to see her. Until the day she died. Her sister could not bathe and clothe her before she was put into the coffin, saying that she had never before performed such tasks and that she would not start that day.[xxix] She was terribly scared to handle a dead body. Well, it was me who did all this for her. The dead woman’s husband arrived that day and he was very thankful to me. He wanted to give me money and medicine to cleanse me from [the supernatural pollution contracted when] handling the dead body. But because I am a religious woman I refused all these offers.

(33) ‘Or take the case of this woman whose husband deserted her. These two people came from Livingstone[xxx] and were on their way to Chipata, when the man disappeared leaving his wife stranded at Kamwala Bus station.[xxxi] The wife inquired from people where she could find Legion people and she was directed to Kapemperere. In Kapemperere people took her to my house, for I am the leader of Action. I looked after this woman well, giving her food and K6 to return to Livingstone. Only last week I received a letter from this woman thanking her for the service I had done.

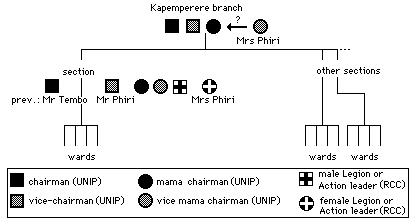

Figure 2. Political and

religious offices in Kapemperere township.

(34) ‘You know what? People cannot fail to recognise it in the end, if you are really a good Christian and care for your neighbours and even strangers. That is why I could become the woman’s Vice-Mama-Chairman, here in Kapemperere. And I just heard from informed sources that a group of women has decided to elect me as full chairman in the next elections. The present chairman wishes to resign for personal reasons. My husband, Mr. Phiri, is also an important man in politics around here. He is Vice-chairman of our section in Kapemperere. He is also Vice-Chairman of businessmen in Kapemperere.

(35) ‘Mr. Tembo used to be chairman of that section but was voted down because he had no respect for his people and was not helpful. Only recently he and his wife were involved in a subversive act. They prepared a torch to go and burn down somebody’s house. They were reported to the police and their case is now with the magistrate awaiting judgement.

(36) ‘Really, I do feel so sorry for Mr. Tembo because he is out of work and has no means of providing properly for his family. Mr. Phiri keeps urging Mr. Tembo to find work quickly for the sake of the children. It is not good to let your son-in-law carry the whole burden of supporting his in-laws, even to the extent of neglecting his duties to his own parents and younger brothers and sisters!’

5. Discussion[xxxii]

Mrs. Phiri’s monologue highlights, in a complex manner, our above discussion of elements of continuity and transformation in the urban social structure.

The first part concentrates on the established Christian churches in the township, and particularly their lay organisations. The church appears under a number of different but related headings: as a local formal organisation, as a structure of material and ideological/spiritual assistance, and finally as a structure of social control.

5.1. A local formal organisation

First the church (and within the church particularly the lay organisation whose social process appeared to be firmly in the control of local Zambians of the township (8)) is presented as a social field whose territorially-based organisation and formal status hierarchy offer new opportunities for leadership, prestige and power, within the context of a bureaucratic logic that also pervades other sectors of the modern Zambian society.(2)

As the township is being formed and its administrative territorial layout defined, formal religious organisations appear, as if to saturate the new social space thus created.(1) The local, urban organisation of the church derives from and strictly follows a non-religious administrative organisation: that of the dominant political party.(2) Kapemperere, a suburb at the eastern fringe of Lusaka, in its totality formed a branch, divided up into a number of different sections, each section consisting of a number of wards; this organisational structure was primarily created by the United National Independence Party (UNIP), but was soon carried over into many other aspects of life, including church organisation. The correspondence between the church and the overall formal organisational pattern of the centre of contemporary Zambian society is invoked, in the account, in terms of a bureaucratic logic (2), e.g. the patterning of time according to a universal calendar, which dictates a fixed and repetitive routine of activities; and the formal, stilted language in which these activities are described and endowed with the respectability that ultimately derives from bureaucratic, legal authority in the sense of Max Weber (1969).

Yet, as we shall see below, organisational boundaries are not jealously maintained, and a considerable convergence between churches, and between churches and other voluntary organisations is hinted at in Mrs. Phiri’s account.

The opportunities this offers for the generation of status and power within the township will become clear in the course of our discussion.

5.2. A structure of material and ideological/spiritual assistance

Next the church is described as a structure of material and ideological/spiritual assistance.(2)

Here the church’s universalism is emphasised: its activities are not confined to members, but extend to former and potential members.[xxxiii](3) Towards the end of Mrs. Phiri’s account, the universality of the church idiom is further expressed by geographical references that stretch across the vast Zambian territory.(32, 33)

Thus the church constitutes an urban-based organisation that seeks to maintain its membership, and to expand it by appropriate services to non-members.(3)

These assistance functions of the church are realised in close co-operation with the lay organisations of certain other local churches within the suburb.[xxxiv] These churches may have a similar organisational structure, ideology and history (they are established mission churches under North Atlantic or South African dominance); yet it is remarkable that this ecumenical co-operation is achieved across major organisational and historical lines: the Protestant churches belong to the Christian Council of Zambia, of which the Roman Catholic Church is not a member.(4) With regard to the local urban community denominational distinctions tend to become rather blurred.

The church as a relief organisation (5, 7) offers crisis support (in cases of illness, death, funerals, destitution etc.) which in other (particularly: rural) Zambian situations is provided by kin, clans, neighbours; and which in urban Zambia, as elsewhere in the modern world, may also be offered by a variety of voluntary organisations, including political parties,[xxxv] or by the state. In this respect the church’s lay organisation may be said to offer, in town, a functional alternative for ‘traditional’ rural forms of social organisation — with this proviso that also in heavily Christianised rural areas of origin the same church-based alternatives can be seen to operate: church women’s groups are not a typically urban phenomenon in Zambia. In other words, along with a transformation of rural ‘traditional’ forms we see here a continuity of rural ‘modern’ forms as represented by voluntary organisations. However, even this continuity undergoes some transformation in town, due to the greater ethnic and regional heterogeneity of the urban scene as compared to the rural areas, the greater flux of migrants and travellers in town, and the fact that in the rural areas church-based women’s group are more likely to coincide, in part, with local residential and kin groupings.

The church does operate as a support and reception structure for urban migrants (7, 33), also to the extend of assisting them in returning to their village homes when continued urban residence has become undesirable.

In offering these forms of support, the church’s tendency to universalism, further corroborated by inter-denominational co-operation, may reveal an aspiration to encompass as much as possible of the entire social life of the township, also in its non-religious aspects. The format in which this support is offered (by a collectivity of local lay women) makes it all the easier to merge with the township’s overall social process. The practical assistance is combined with Christian elements such as prayer (7), yet remains close to the ordinary, secular services kinsmen and neighbours would offer in such situations.

But however close these services by the church’s lay organisations may come to the traditional rural kin pattern, the emphatic Christian idiom within which they are presented constitutes an essential transformation here. Such an idiom provides a framework of one-sided exchange that radically defeats the kin-based assumptions of reciprocity and equality. The lay agents bestow services without accepting the appropriate traditional payments, and without belonging to the social categories (funerary kinsmen, fixed pairs of clans that stand in a joking relation vis-à-vis one another) that in the traditional rural context are under the obligation to offer such great services free of charge. Thus the lay agents accumulate obligations among non-kin inhabitants of the township — a social capital which (as Mrs. Phiri very well realises) can subsequently be converted into religious and/or political power within the suburb.(32, 34)

Also Mrs. Phiri’s excessively high income as an entrepreneur,[xxxvi]we might suggests that, in her case at least, the Christian idiom, the organisational and leadership structure it offers at the local level, and the opportunities to engage in unequal relationships, have provided her with the major mechanism through which to convert economic capital into social power and political capital within the emerging urban community of Kapemperere. Her picturing of church work and of the urban community has a strongly elitist, hierarchical flavour (cf. the passage on concealing scandals, or the condescension towards poorer people that attends her self-image as a Christian women). This reflects her formidable aspirations for status and power both at the domestic and at the community level, and makes her into an exponent of the emerging class structure of Zambian urban society.

The instrumental potential of the Christian idiom appears to virtually eclipse any specifically Christian religiosity. Against the background of the autochthonous world-view featuring sorcery, possession spirits and medicines, Mrs. Phiri’s brand of Christianity concentrates on rules of conduct, and on formal organisation. This may befit, perhaps, an ambitious member of an established mission church, but is by no means a constant feature of Christianity in Lusaka.

Meanwhile it is remarkable that Mrs. Phiri’s account already allows us to discern a historical pattern in the rural/urban continuity of crisis intervention by voluntary organisations as a functional alternative to kin support. She claims that in the past the church would extend its funerary care to include a quasi-kin responsibility for the surviving children (sc. in the rural areas), but that this has gone in disuse now.(7) This then is a point where the quasi-kin aspirations of the church reach a limit, which leaves room for other (kin-based, humanitarian or state) agencies for crisis support.

Remarkably, a parallel structure of male and female leadership, and in general a strict gender-specific pattern of organisation is observed, (5, 7) which does not stem from the logic of the church as a formal organisation but appears to reflect one of the constants of both urban and rural life in South Central Africa: a fairly rigid division of labour and of social organisation between the sexes. Here we encounter an element of continuity, a rural input that is applied in town without first being totally transformed. A similar gender parallel returns in the political careers of Mrs. Phiri and her husband.[xxxvii] (34)

5.3. A structure of social control

Finally, the church’s lay organisations in the township is presented as a structure of social control (9, 10).

Here Mrs. Phiri’s discussion of ‘backsliding’ (6) is particularly relevant. In the Zambian Christian idiom, ‘backsliding’ is an expression for an adherent’s failure to live up to the strict moral code imposed by the church: monogamy, responsible family life, moderate drinking habits, avoidance of criminal offences, etc. In fighting ‘backsliding’, the church is not merely protecting its membership quota but also exerting a more general form of social control, which is all the more important in the expanding urban environment, — a new suburb where neighbourly relations, voluntary associations and bureaucratic agencies such as the police have not yet been fully established.

In this context it is relevant that, in accordance with a South Central African underlying pattern that applies both in urban and rural areas, individual’s sexual behaviour is to a considerable extent subjected to public scrutiny and sanctioning. Not only rape but also adultery and pre-marital sex constitute offences actionable in formal state courts of law and before such customary, more informal judicial bodies as may provide functional alternatives to such courts: family moots, the adjudications of village headman and UNIP urban ward leaders. In contemporary Zambia, both in rural areas and in towns, such informal judicial micro-processes can be seen to operate all the time, and domestic and sexual matters are among their main topics. It is therefore highly significant that the township church lay organisations assert themselves as a judicial functional alternative in precisely these matters, in a situation where (given the tender age of the township) family moots and ward leaders are still imperfectly operative, while the urban court is both distant and generally considered to lead to too drastic a breach of neighbourly and kin relations to offer real redress. The universalism of the church, its extension to non-members for material support and for a proselytism generally cast in moral terms, coupled to the fact that many marriages and other sexual unions are religiously mixed,[xxxviii] guarantee the church a very real share of the ongoing informal judicial process in the emerging township.

In addition to the fact that here communal concerns are taken on by a specifically organised minority of church leaders without a general mandate from the community, a significant transformation here concerns the church’s emphasis on secrecy.(10) The latter element does not form a traditional rural pattern,[xxxix]but seems to relate to the fact that the church people’s authority is imperfectly legitimated: it does not spring from traditional authority, nor from the post-colonial state and its formal judicial institutions, and it is exercised in a heterogeneous urban environment where many people do not formally subscribe to that authority even although, in an informal and diffuse manner, Christianity has managed to become some sort of a Great Tradition hovering above the many particularistic and autochthonous religious forms as found today (cf. van Binsbergen 1981). The secrecy also protects the internal cohesion of the church membership, which could be negatively affected if use would be made of external, non-religious agencies of social control (urban court, but also family moots) — and at the township level these are discouraged by the church, as Mrs. Phiri’s statements suggest.(11)

As her account of her own marital conflicts already indicates, the church-based structure of social control may not prevent temporary disruption of marital relationships, extramarital sex, concubinage etc.; but it does offer a structure of redress which at times may be effective; in this particular case, with regard to a type of marital conflict which is very commonplace in urban Zambia (12), the effectiveness may be related to the considerable status benefits the church had to offer both spouses when complying with the church’s intervention.

When aspiring to social control in domestic and sexual matters the church’s lay organisation in the township again partially emulates the rural model of kinship. Hence the church agents can offer pre-marital training, can act as go-betweens between bride-givers and bride-takers (9), and partially organise and finance the wedding. Likewise, when the church laity confronts a non-member husband in order to allow the wife to attend church services, this smacks rather of a kin group scooping down on a stubborn son-in-law in order to assert a daughter’s personal rights in the face of marital pressure.

However, there are clearly two transformations involved here (both again rather of the modern/traditional than of the urban/rural type): the rules of conjugal behaviour are cast in a Christian idiom (and thus considerably deviate from rural custom (9)), and the woman’s protagonists are only fictitious (or quasi-) kin. Although imitating essential elements of traditional kinship and marital structures, the church offers not a continuation but an alternative.

We ought to appreciate at this point that the church takes on this quasi-kinship role not exclusively for lack of kinsmen in town. Lusaka, and among the Lusaka townships Kapemperere particularly, houses very many people from a Catholic background and from Eastern Zambia, many recent urban migrants can in fact make use of kin-based reception structures when looking for housing and employment, and it would often be quite easy to bring together the necessary people for an informal family moot. Therefore, an important factor in the reliance on church-offered alternatives seems to be that the townsmen involved are somehow past the stage where they would have sought, and accepted, direct rural intervention: since much of their urban life constitutes a transformation of rural forms, they would seem to insist also on transformed patterns of social control and domestic conflict regulation. The church then deliberately takes on neo-traditional forms and patterns of social relations in order to articulate itself as an alternative quasi-kin structure emulating but at the same time replacing (and competing with) the original kin model.[xl]

Part of this process is that a new model of conjugal propriety is proffered: the Christian marriage, which gives the church agents a clear-cut model to enforce and a recognisable focus for the social control they seek to wield.

Aspiring to exercise social control over the believers’ bodies, actions and thoughts, the church lay organisations virtually claim as much influence over the pre-marital phase as the institutions of puberty training used to do in the pre-Christian setting of Eastern Zambia and Malawi. Stipulating very severe disciplining[xli] even for the parents of the betrothed in case of pre-marital sex, it is clear that the church people encroach on and if possible usurp the parents’ responsibility over the would-be spouses. All this of course must be seen in the light of the Catholic church’s then[xlii] still absolute rejection of traditional puberty training and the elements of initiation and pre-marital sex it may entail.(9)

5.4. Traditional idioms of power

The lay organisation’s desire to wield social control over the domestic, marital and sexual domain combines with an implicit moral obligation to protect the community from sorcery. In the traditional rural model the latter has been a typical concern of village headmen and higher-level chiefs. While the church action against sorcery is presented in an idiom which suggests that sorcery is unchristian, this does not mean that sorcery no longer exists as a frame of reference and as a theory of causation. On the contrary, sorcery beliefs remain a touchstone of community leaders’ political and moral effectiveness, even in town: Mrs Phiri suggests (in line with an abundance of converging evidence that falls outside our present scope) that the church people could not exert social control if they would shrink from the responsibility to battle against sorcerers — the greatest evil perceived traditionally in the societies of South Central Africa; so here again continuity and transformation at the same time.(13)

The respondent is clearly aware of the fact that the sorcery dimension stems from a source of inspiration outside church Christianity.(14) And she proceeds to invoke yet another idiom of power, causation and control, that of spirit possession (15), which, despite its potential for biblical reinterpretation, is clearly presented as in the domain of traditional rural continuity. There is a strong suggestion that these traditional idioms represent, on the part of the respondent, an additional claim to power, meant to support and augment such power as she derives, in the township, from her church and party work.(15, 17) However, she feels obliged to redefine, transform, the collective representations of the mashabe spirits so as to bring them in line with her Christianity — they have to be made into a type that does not give offence in terms of church regulations and prohibitions!

5.5. An inter-generational and affinal drama within the township

The second half of Mrs. Phiri’s account largely describes an intricate social drama in which the various strands indicated above come together and interact upon each other. We see her invoke a number of different idioms of power, and portray a number of agents of social control, between which she cleverly (yet far from successfully) switches in an attempt to articulate her aspirations of power and success, both in the domestic sphere and within the wider social field of the new township.

The conflict has at least two levels: the domestic sphere, and that of the evolving political and class structure of Kapemperere township.

First the domestic level. When the son is introduced it becomes clear that religious and political achieved status in his parent’s generation of urban immigrants has sought consolidation in the form of a relatively well-trained modern vocation in their children’s generation.(18) In the mother’s (Mrs. Phiri’s) perception, these investments are to pay off: (a) in the form of the son’s assistance to the parents’ household expenditure, and (b) through Mrs. Phiri’s matronly control over her son’s newly created family, and particularly over her daughter-in-law’s domestic labour power.(19) Tensions and conflicts generated by the sheer confrontation between the family of orientation and that of procreation are part and parcel of Zambian rural (in this case: Nsenga, matrilineal) society; there is certainly an element of rural-urban continuity of traditional kinship structures here. However, these tensions tend to urban transformation in so far as they are allowed to become exceptionally virulent and insoluble — particularly because the framework of affinal relationships on which the son’s newly formed nuclear family was to define itself, proved utterly brittle and ineffective. The binding relationship between the affines prior to marriage was not kinship but residential propinquity (they were neighbours in Kapemperere). This rather loose single-strandedness precluded such dissipation of the built-in conflicts as might otherwise — especially in most rural settings — have taken place at an early stage through the familiar mechanisms of conflicting loyalties and crosscutting ties. Escalation, and intervention of the available formal conflict regulating agencies (police, urban court) thus became necessary. And even so the conflict was not really redressed but lingered on beneath the surface, as sorcery accusations and contemplated sorcery actions.

In the parents’ situation as Christian leaders, and given the aspirations and the actual role of Christianity in Kapemperere township, an obvious way to strengthen the son’s affinal framework and thus to resolve the built-in conflicting tendencies, would have been to contract a marriage that was not only Christian in form and appearance but that also involved committed Christian affines. In such a way brittle ties of propinquity could have been reinforced by the more comprehensive ones of co-religiosity, and the quasi-kinship Christianity so obviously seeks to generate in Kapemperere. However, the ambitions of Mrs. Phiri and her husband went beyond a balancing of inter-generational conflict, even beyond domestic power. They extended to the ward and section level, and despite an instrumental Christianity were politically rather than religiously orientated. Therefore they favoured a marriage with the daughter of the politically successful Mr. Tembo, who was not a Christian. Thus possibilities for the gentle dissipation of such conflicts as are inevitably generated in any Nsenga marriage were cut off: as local agents of social control and of conflict regulation, neither the church (to which only the Phiris belonged (18)), nor the party (within which the Phiris and the Tembos appeared to be deadly rivals, with Mrs. Phiri taking the upper hand in the end) remained available for them. Therefore the conflict rapidly escalated; it assumed forms which are utterly indecorous particularly in view of the political and religious status of the protagonists in the Kapemperere community, and in the end turned out to be insoluble.

Victims to a strange hubris, the Phiris deprived themselves, as church leaders, from the very services their organisation so generously extended to the other inhabitants of Kapemperere. The fact that the son’s prospective in-laws were not Christians was not even allowed to form an obstacle to his Christian wedding.(18) Also the subsequent affinal struggle for domestic and family power was hardly patterned or mitigated by Christian considerations.(21, 24) When the affinal conflict came to a head, the township’s church organisation is not even considered as an agent of conflict regulation. Instead various other agents are stressed:

(a) The party, which initially (when the party Youth wing tries to intervene) remained ineffective, but which later asserted itself as an agent of social control in the township. It is only at this point that Christianity is invoked, merely as an excuse to opt out of the conflict resolution the local party leadership was advocating.(23)

(b) The local police, effective in separating the fighting protagonists.

(c) The urban court (25), which takes precedence in settling the case even if its formal adjudicating power is not wholeheartedly supported by the township party leadership (26).

Unable, thus, to emerge triumphant through the operation of formal, modern agents of social control, and evidently having lost the kin battle in which she found herself confronting not only her daughter-in-law and the latter’s parents but also her own son, Mrs. Phiri reverts back to the ancient idiom of power: a sorcery interpretation of the conflict, and a continuation of the struggle along sorcery lines.(28, 30). The unconvincing use of an idiom of generalised Christian charity can barely conceal her spite at not being able to attain the domestic power she aspired to.(31)

And in this eminently successful urban woman, the loss of her

son’s loyalty in combination with her resorting to the idiom

of sorcery ever so faintly evokes one of the most powerful

collective representations of South Central African society

— an image of great rural-urban continuity that, in its

sinister implication of the insolubility of inter-generational

conflict, seems hardly in need of transformation: the

parent who through sorcery sacrifices his or her child in

exchange for magical success in the entrepreneurial, medical or

political field.

6. Conclusion

My analysis of the material as presented has sought to illuminate aspects of the contemporary urban situation of Zambia, suggesting that social relationships found there, and the social process to which they give rise over time, are shaped by the subtle, kaleidoscopic and creative dialectics between traditional, rural-based continuity and modern urban-based transformation. The formal organisations, such as churches, by which modern urbanites structure their urban life assume functions and aspirations which can only be understood against the background of pre-existing rural traditional patterns, yet cater for needs of crisis support, social control, conflict regulation and the expression of group identity, leadership and an emerging class structure as are specific for the urban environment. This provides a framework within which to identify, trace and understand urban social processes such as they manifest themselves at the micro level of urban social dramas, but only on the basis of a consideration of both rural continuity and urban transformation. The pattern of relationships that thus opens up for analysis turns out to be as unmistakably urban, modern and transformative, as it remains faithful to the patterns of South Central African cultural orientation so adequately established by the anthropology of earlier decades.

References cited

Barnes, J.

1951

Marriage in a changing society,

Manchester: Manchester University press, Rhodes-Livingstone Paper

20.

Dillon-Malone, C.M.

1978

The Korsten Basketmakers,

Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Epstein, A.L.

1958

Politics in an urban African community,

Manchester: Manchester University Press.

1969

‘The network and urban social organisation’, in:

Mitchell 1969: 77-116.

1981

Urbanisation and kinship: The domestic domain

on the Copperbelt of Zambia 1950-1956,

London etc.: Academic Press.

Glazer Schuster, I.M.

1979

New women of Lusaka,

Palo Alto (Cal.): Mayfield.

Harries-Jones, P.

1981

Freedom and Labour,

Oxford: Blackwell.

Heisler, H.

1974

Urbanisation and the government of migration:

The inter-relation of urban and rural life in Zambia,

New York: St Martin’s Press.

Johnson, W.R.

1974

‘The history of the A.M.E. Church in Zambia’, The

Journal of the Interdenominational Theological Center,

2, 1: 55-68.

1977

Worship and freedom: A Black American church

in Zambia, New York: Africana Publishing

Company.

1979

‘The Africanization of a mission church: The African

Methodist Episcopal Church in Zambia’, in: G. Bond, W.

Johnson, & S.S. Walker (eds.), African

Christianity: Patterns of religious continuity,

New York: Academic Press, pp. 89-107.

Jules-Rosette, B.

1975

African Apostles,

Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

1977

‘Grass-roots ecumenism’, African

Social Research, 22: 185-216.

1979

‘Prophecy and leadership in the Maranke church: A case study

in continuity and change’, in: G. Bond, W. Johnson, &

S.S. Walker (eds.), African Christianity:

Patterns of religious continuity, New York:

Academic Press, pp. 109-36.

1981

Symbols of change: Urban transition in a

Zambian community, Norwood (N.J.): Ablex.

Keller, B.

1978

‘Marriage and medicine: Women’s search for love and

luck’, African Social Research,

26: 489-505.

Long, N.

1968

Social change and the individual,

Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Mitchell, J.C.

1956

The Kalela dance,

Manchester: Manchester University Press, Rhodes-Livingstone Paper

27.

1965

‘The meaning of misfortune for urban Africans’, in M.

Fortes & G. Dieterlen (eds.), African

systems of thought, Oxford University Press

for International African Institute, pp. 192-203.

1969

(ed.) Social networks in urban situations,

Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Parkin, D.

1975

‘Town and country in Central and Eastern Africa:

Introduction’, in: D. Parkin (ed.), Town

and country in Central and Eastern Africa,

London: Oxford University Press for International African

Institute, pp. 3-44.

Powdermaker, H.

1961

Coppertown: Changing Africa,

New York: Harper & Row.

Rasing, T.

1994

‘Passing on the rites of passage: Girls’ initiation

rites in the context of an urban Roman Catholic community on the

Zambian Copperbelt’, M.A. thesis, department of Cultural

Anthropology/ Sociology of Development, Free University,

Amsterdam; revised version in press with African Studies Centre,

Leiden.

Shorter, A.

1991

The church in the African city,

New York: Orbis.

Stefaniszyn, B.

1962

‘Inter-tribal relations in the Catholic church in Northern

Rhodesia’, in: Dubb, A.A. (ed.),The

multitribal society, Lusaka:

Rhodes-Livingstone Institute, Rhodes-Livingstone Institute

Conference Proceedings, pp. 105-10.

Sundkler, B.

1961

Bantu prophets in South Africa,

London: Oxford University Press, 2nd edition (1st edit. 1948).

ter Haar, G.

1991

Spirit of Africa: The healing ministry of

archbishop Milingo of Zambia, London:

Hearst.

van Binsbergen, W.M.J.

1979

‘The infancy of Edward Shelonga’, in: S. van der Geest

& K.W. van der Veen (eds.), In search of

health, Amsterdam: Anthropological

Sociological Centre, University of Amsterdam, pp. 19-90.

1981

Religious change in Zambia,

London/Boston: Kegan Paul International.

1985

‘From tribe to ethnicity in Western Zambia’, in: W.M.J.

van Binsbergen, & P.L. Geschiere (eds.), Old

modes of production and capitalist encroachment,

London/Boston: Kegan Paul International, pp. 181-234.

1991a

‘De chaos getemd? Samenwonen en zingeving in modern

Afrika’, in: H.J.M. Claessen (ed.), De

chaos getemd?, Leiden:

Faculty of Social Sciences, Leiden University, pp. 31-47.

1991b

‘Becoming a sangoma:

Religious anthropological field-work in Francistown,

Botswana’, Journal of Religion in Africa,

21, 4: 309-344.

1993a

‘Making sense of urban space in Francistown, Botswana’,

in: P.J.M. Nas, ed., Urban symbolism,

Leiden: Brill, Studies in Human Societies, volume 8, pp. 184-228.

1993b

‘African Independent churches and the state in

Botswana’, in M. Bax & A. de Koster, eds., Power

and prayer: Essays on Religion and politics,

Amsterdam: VU [ Free University ] University Press, pp. 24-56.

van Velsen, J.

1964

The politics of kinship,

Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Verstraelen-Gilhuis, G.

1982

From Dutch mission church to Reformed Church

in Zambia: The scope for African leadership and initiative in the

history of a Zambian mission church,

Franeker: Wever.

Weber, M.

1969

The theory of social and economic

organization, Glencoe: Free Press.

Wiley, D.S.

1971

‘Social stratification and religion in urban Zambia: An

exploratory study of an African suburb’, Ph.D. diss.,

Princeton Theological Seminary, Princeton.

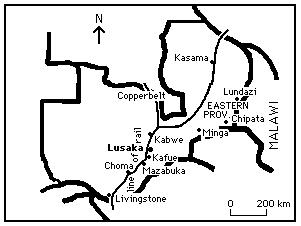

Figure 3. Topographical

references.

[i] An earlier version of this paper was read at the wuoo (Netherlands Association of Urban Studies in Developing Countries) Conference on African Towns, Leiden, February 26-28, 1985. The data on which this paper is based were collected, by the author and his competent and resourceful assistants Messrs. P.A. Mutesi and D.K. Shiyowe, in the course of field-work in Lusaka, Zambia, in the period February 1972 to July 1973. The project (initially entitled A sociological study of religion in Lusaka) was started off by a K625 grant from the Research and Higher Degrees Committee of the University of Zambia, which covered transport expenses and payment of one research assistant from February through April, 1972. A further subsidy of us$500 from cromia (The Churches’ Research on Marriage in Africa) made it possible to extend the project, from March through May 1973, by means of a survey of urban marital structures, social control, and the role of churches therein. Quantitative analysis was undertaken by the author at the Technical Centre of the Faculty of Social Sciences of the municipal University of Amsterdam, by means of computer time voted by the department of Cultural Anthropology of that University — where I was a wotro (Netherlands Foundation for Tropical Research) research fellow in the years 1974-75. Further work on this material was made possible in the course of my appointment at the African Studies Centre, which also enabled me to repeatedly revisit Lusaka in the years 1988-1995. For the data collection and analysis phase, I wish to register my indebtedness to: R. Hatendi, H. Hinfelaar, A. Shorter, L. Steen, H. van Schalkwijk, J. Veitch, J. van Velsen, and C. Woodhall; the Registrar of Societies (Lusaka); the unip (United National Independent Party) Regional Office (Lusaka); The District Secretary’s Office (Lusaka); Mindolo Ecumenical Foundation (Kitwe); numerous members and leaders of Lusaka churches and church organizations; and an even greater number of Lusaka residents approached as respondents during our surveys and depth interviews. Further I am grateful to R. Bergh, W. Heinemeyer, D. Jaeger and L. van de Berg for helpful comments on an earlier draft.

[ii] E.g. Epstein 1958; Mitchell 1956, 1969; and, outside Rhodes-Livingstone circles, Powdermaker 1961; for a more general background, cf. van Binsbergen, ‘African towns: The sociological dimension’, this volume, supra.

[iii] Cf. Dillon-Mallone 1978; Johnson 1974, 1977, 1979; Jules-Rosette 1975, 1977, 1979, 1981; and, less specifically on Lusaka, Verstraelen-Gilhuis 1982.

[iv] More recently I had the opportunity of pursuing these topics in extensive anthropological field-work in a different Southern African urban context, that of Botswana’s rapidly growing Francistown; cf. van Binsbergen 1991a, 1991b, 1993a, 1993b.

[v] Cf. Epstein 1969; Mitchell 1969; I have earlier used this approach in a context of the ethnography of urban and rural health care in Zambia: van Binsbergen 1979.

[vi] Author’s research archive, ‘usoco Red Notebook I’, interview no. 21, Mrs. Evelyn Phiri, born in Eastern Province c. 1925, ethnic affiliation Chewa or Nsenga; interviewed 13.4.1972, in her house in Kapemperere, no other informants present, language Nyanja. Mrs. Phiri’s name is a pseudonym. All personal names used in this paper are likewise pseudonyms, and so is the name of Kapemperere township; the other Lusaka townships mentioned have however retained there real names. Paragraphs have been numbered between parentheses in order to facilitate cross-references.

[vii] Churches in Lusaka range from (a) established mission churches with a world-wide coverage (e.g. Roman Catholic Church, Reformed Church, Anglican Church, Scottish Presbyterian Church — a further classification would be needed with regard to degree of fundamentalism, pentecostalism, attitude vis-à-vis secular life and the African cultural heritage etc.), via (b) an intermediate range of churches whose foci of control, finance and spread were to be found outside Zambia but which, in terms of politics and class, have less of an establishment position in Zambian society (e.g. Watch Tower, New Apostolic Church, Apostolic Faith Church), to, finally, (c) a large group of numerically small independent church bodies, often the result of splits (either in Zambia or elsewhere in South Central Africa) from churches belonging to the other two types, or from splits within this third category itself. The discussion of Mrs. Phiri’s case should not be taken to imply that the same pattern of social control and negotiation of rural-based traditional continuity would apply equally to the second and third categories: with all qualifications their variety and heterogeneity call for, those churches would seem to observe much firmer boundaries between their membership and the large community of non-adherents, to be more some aloof vis-à-vis the state and the party, and to be more explicit, selective and intolerant vis-à-vis traditional elements. However, the established churches (category a) dominate on the Lusaka Christian scene; e.g., a random sample of 165 townsmen subjected to depth interviews turned out to contain 102 Christians (62%), of whom more than half already (54, i.e. 53%) were Roman Catholics; Author’s research archive: ‘Urbanization, church and social control: A survey of Lusaka, Zambia, 1973: Summary of quantitative results — Part 1. USOCO results book II’, p. 53. A footnote below gives a further breakdown of these results.

[viii] Neither Catholic Action nor the Legion of Mary (see below) are features peculiar to Roman Catholicism in Lusaka or Zambia: they are local branches of lay organizations which are to be found virtually wherever Roman Catholicism has taken root.

[ix] Kapemperere, a suburb at the eastern fringe of Lusaka, in its totality formed a branch, divided up into a number of different sections, each section consisting of a number of wards; this organizational structure was primarily created by the United National Independence Party (unip), but was soon carried over into many other aspects of life, including church organization.

[x] a.m.e.: African Methodist Episcopal Church, a long-established North American Christian denomination imported into southern Africa by the end of the nineteenth century, and among the few Christian churches which unambiguously supported the Zambian struggle for independence; cf. Johnson 1974, 1977, 1979. In the three churches mentioned, the lay organizations equivalent to Catholic Action are, of course, called by different names — contrary to what the respondent suggests.

[xi] Especially in urban areas, in Zambia the available number of places at primary and secondary schools tends to fall short of the actual demand, so people have to be very resourceful if they want to get their children placed.

[xii] Minga is a Roman Catholic Mission in Eastern Province, Zambia, c. 300 km. east of Lusaka.

[xiii] K: Kwacha, the Zambian currency; at the time of the research, K1 equalled about us$1.32.

[xiv] A Catholic priest’s professional title in Nyanja; the basic meaning of bambo is: Sir.

[xv] Elaborate negotiations between bride-takers and bride-givers, with a prominent role assigned to a third party acting as go-betweens, are a well-known feature of marital systems in eastern Zambia and Malawi; cf. Barnes 1951; van Velsen 1964.

[xvi] Courts, both urban and rural ones, are very frequently resorted to in Zambia, also for cases involving a breach of respect, bodily integrity, accusations of being a sorcerer, etc. For a small amount (K0.50) the plaintiff files the case, after which the defendant is summoned to the court; for this reason initiating a court case is called, in Zambian English, buying a summons.

[xvii] Implicit reference is made to the belief, widespread in Southern Central Africa, that being a sorcerer means that one has a personal, and indissoluble, contract with an invisible sorcery familiar; the sorcerer provides the familiar spirit with the means to harm and kill other human beings, in exchange for secret benefits reaped by the sorcerer. If the sorcerer attempts to break the terms of the contract, he or she, too, is supposed to fall victim to the familiar.

[xviii] On witch-finding, a widespread institution in South Central Africa, cf. van Binsbergen 1981: ch. 4, and references cited there. The analytical anthropological distinction between sorcerer and witch was not made in the Nyanja discourse.

[xix] Witch-finding in twentieth-century Malawi as a rule combines Christian or Biblical elements with autochthonous ones, and it may not be too far-fetched to interpret this small frontal tattoo partly as emulating Cain’s sign (Genesis 4: 15).

[xx] The informant here refers to cults of affliction, a dominant religious idiom in twentieth-century South Central Africa; cf. van Binsbergen 1981: ch. 4-7, and references cited there.

[xxi] Kabwe is a town along the Zambian ‘line of rail’, c. 150 km north of Lusaka.

[xxii] Chipata is the capital of Zambia’s Eastern Province.

[xxiii] The youth wing of unip; here reference is made to its self-appointed role of enforcing law and order in the townships.