‘AN INCOMPREHENSIBLE MIRACLE’

Central African clerical intellectualism versus African historic religion: A close reading of Valentin Mudimbe’s Tales of Faith (full version)

Part 4. Historic African religion

Wim van Binsbergen

|

‘AN INCOMPREHENSIBLE MIRACLE’ Central African clerical intellectualism versus African historic religion: A close reading of Valentin Mudimbe’s Tales of Faith (full version) Part 4. Historic African religion Wim van Binsbergen |

|

Proceed to:

Part 0. Introduction and links to

other parts

Part 1. Mudimbe's method

Part 2. Clerical

intellectualism in Central Africa

Part 3a. Mudimbe's homelessness: No African home,

Afrocentrism, death

Part 3b. Mudimbe's homelessness: plurality of African

cultures; death; métissité

Part 5. Conclusion: Mudimbe's and van

Binsbergen's itineraries compared

Remarkably, I have not yet spotted any passage in Mudimbe’s oeuvre (but I may easily have missed it considering its size and bilingual nature) where the concept of parricide is equally applied to the unmistakable lack of demonstrable retention of any historic Central African religion on the part of these clerics and (like Mudimbe himself) post-clerics. They tended to be second or third generation Christians, and hence one might surmise that others had done the killing of local historic religion for them: their own parents, and the missionaries who had somehow managed to substitute themselves as father figures in the place of the paternal kin of these African clerical intellectuals. The message, so implicit as to be entirely taken for granted, of Mudimbe’s kaleidoscopic and multi-genre narrative of the itinerary of these African clerical intellectuals in his book Tales of faith, is that by the middle of the twentieth century none of them was in direct personal contact any more, as a practitioner, with Central African historic religion. Kagame’s search as a student at the major seminary, after La philosophie bantu-rwandaise de l’Être,[1] was a retrieval, a reconstruction on the basis of deliberate research. Mudimbe had to base his own highly recommendable close readings of Congolese myth of genesis and other historic religious texts on an experience testifying to his cultural homelessness:

‘My experience would define itself somewhere between the practice of philosophy with its possible intercultural applications[2] and the sociocultural and intersubjective space which made me possible: my Luba-Lulua mother, my Songye father, the Swahili cultural context of my primary education in Katanga (Shaba), the Sanga milieu of my secondary education from 1952 to 1959 in Kakanda, near Jadotville (Likasi), and, later on, at the Catholic seminary of Mwera, near what was then Elisabethville, and my brief sojourn in a Benedictine monastery in Rwanda.’[3]

Beyond what is implied and hidden in such local languages as one learns to speak as a child and a teenager, one can hope to inherit but very little of historic African religion in such an itinerary from the age of five or six on. It is therefore unlikely that, instead of the previous killing of this paternal culture by others, a different mythical scheme should be invoked here: African historic religion, Africa in general as a myth and a concept, does not consciously appear here as the mother however prominent that image is in the construction of that continent by writers as diverse as Basil Davidson and the Afrocentrist ben-Jochanan.[4] There appears to be no deliberate maternal imagery of Africa in Mudimbe’s work, no attempt to direct a filial mystique of love and identification upon the idea of that continent. Only by gross imposition might one interpret Mudimbe’s consistent, repeated, and relentless deconstruction of the idea of Africa in his two best known books (The invention of Africa, 1988; and The Idea of Africa, 1994)[5] as an attempt at matricide. Meanwhile his consistent refusal to celebrate Africa as the self-evident focus of Black identity and even — in terms of strong Afrocentrism — as the source of all human civilisation might be interpreted as fratricide by the many African American, and African, Afrocentrists holding such views.[6] I am inclined to read Mudimbe’s relation to historic African religion, and to Africa in general, in terms of yet a different myth: one which derives from the domain of African male puberty rites, and which amounts to the fact that the son dies vis-à-vis the mother, and the mother and her world vis-à-vis the son, at the moment that the son sets out to be initiated in the sacred forest access to which is forbidden to women. His clerical education and subsequent clerical (albeit briefly) and Western intellectual career have constituted for Mudimbe an initiation by virtue of which historic African religion has died on him. It is as the familiar case of the priestly son from a humble rural family in the Roman Catholic, Southern regions of the Netherlands or in Belgium: he visits the house of his mother, and by virtue of his now incomparably elevated status — considered to have left an indelible mark on his soul at ordination — has become an exalted and condescending stranger there, rendered taboo by the almost untenable sacredness which his direct link with Rome and heaven bestow upon him.

‘In itself, the Colonial Library is not so much about preserving past or present narratives, customs and knowledge as constituting a body or bodies having in their own right a particular quality inscribed in a given history, but about bringing together these things and collapsing them in a ‘primitive background’ that a new universe (the colonial) and a new cosmology (conversion) can translate and transform into an advanced modernity. (...) it seems clear that both the Western savoirs des simples as well as the African invented primitive backgrounds could be understood as refused knowledges — that is, as the tragic necessity of an ill-known desire whose origin comes from elsewhere.’[7]

That is magnificently formulated, but it is also precisely what Mudimbe does to African historic religion: reduce it to the status of ‘refused knowledge’.

Spending many pages to arrive at an original definition of religion which should be capable of capturing a finely tuned and critically purified ‘primitive’ religion characterised by the ‘midnight zero qualities of ipse-ity’,[8] Mudimbe never comes round to applying such a definition to Central Africa in order to identify and discuss forms of African historic religion there, but only describes the conversionist and unavoidably distorting appropriations of these forms in the hands of anthropologists, missionaries, and (in a process of creative retrodiction, by which they liberate and assert their difference) by African clerical and post-clerical intellectuals.

Admittedly, the fact that Mudimbe concentrates on varieties of Christianity and does scarcely touch on African historic religion, is to some extent a consequence of a theoretical position which includes Christianity and historic African religion alike:

‘The reconversion — which is actually a rupture — from a psychological to a sociological model and then to Lévy-Bruhl’s anthropological paradigm, exerts an influence upon the way we read the reality of African religions today. The traditional readings are not rendered as part of a cultural order sui generis but, indeed, as signs and proofs of something else, namely, epistemological categories unfolding from an intellectual configuration completely alien to the cultural spaces they claim to reflect.’[9]

African historic religion does however enter the argument of Tales of faith to the extent to which it was appropriated, by certain missionary authors, into Christianity, as a preparatio Evangelii, a stepping-stone towards the Gospel.[10] Such liberation of the oppressed as the learned Cameroonian pastor Ela envisages through his missionary work among his fellow Cameroonians, takes local religious practices seriously and leads to a ‘sometimes iconoclastic ambition’[11] directed as the empty fetishes of missionary Christianity — but what goes unnoticed is the far greater iconoclasm that all but eclipsed African historic religion from visibility in Central Africa. The oppressed poor scarcely manage to summon Mudimbe’s passion: distantly or even callously, he calls Ela’s commitment to their cause ‘fascinating’![12]

When Mudimbe speaks of ‘in incredible miracle’ and identifies as an agnostic, he evokes the epistemological impossiblity of religious belief as a rational position. St Augustine’s credo quia absurdum, in Latin, would be a typical phrase for the post-clerical classicist Mudimbe, to embellish his French or English prose. Yet at least two points can be made in defence of African historic religion, so that it does not have to be crushed under the impact of allegedly universal epistemologies from the North Atlantic. The first point I shall explain be reference to common anthropological ethnocentrism in the study of African religion; the second point is made by Mudimbe himself which relying on de Certeau.

My first point is that Mudimbe’s insistence on the incredible nature of both Christianity and African historic religion reiterates a position which is basically ethnocentric and hegemonic. Regrettably, that position coincides with that habitually taken in the anthropological study of African religion.

In cultural anthropology statements of certain types are eligible to be assessed as true or false:

• the ethnographer’s statement to the effect that her ethnographic description of concrete emic details is valid

• the ethnographer’s statement to the effect that her theoretical, etic analysis is valid

• the individual informants’ statements that they render fact, representations and rules validly

There is however a fourth type of statement which cultural anthropologist absolutely exclude from the question concerning truth:

• the participants’ statement that their collective representations are a valid description of reality (both in its sensory and in its meta-sensory aspect, visible and invisible etc.)

Following the later Wittgenstein Winch has show us that the truth of the latter type of statement cannot be established in general and universally, but depends on the language-specific, meaning-defining form of life which is at hand. Whether in a certain society witches do or do not exist, cannot be answered with tine universal statement that witches do exist , or do not exist, but can only be answered by reference to the specific life forms at hand in that society — and of such life forms there are always more than one at the same time and place.[13] Now, cultural relativism as a central profession point of departure of classic anthropology may perhaps mean, theoretically, that the exclusion of this fourth category depends on respect for whatever is true in the other life form or cultural orientation; but in practice it nearly always comes down to following. However much the ethnographer has invested in the acquisition of linguistic and cultural knowledge so that local collective representations can be unsealed for her, and however much she gradually internalises these collective representations as a private person — in her professional formal utterances (in the forms of academic writing-up) she does not allow the collective representations she has studied, the benefit of the doubt, nor the respect she pretends to be due to the collectively other.

The tacit point of departure of the cultural anthropological professional practice (and in this respect it does not distance itself from North Atlantic society as a whole) is: Collective representations of other societies under study cannot be true, unless they coincide one hundred percent with the collective representations of the researcher’s own society of origin. Of course, both the researcher’s society of origin and the cultural orientation under study construct a truth-creating life world — which is a situation suggestive of a relativist approach. But according to the conventions of ethnography such a life world may be one-sidedly broken down if it is the other’s life world, and left intact when it is the researcher’s own. Just try to realise what this means for the confrontation, throughout the modern world, in institutional, political and media settings, between such major and powerful North Atlantic institutional complexes as democracy, medicine, education, Christianity, and pre-existing local alternatives in the respective fields. The anthropologist may pay lip service to the latter from a humanitarian and aesthetic point of view but — they for he own sanity and professional survival she has to abide by the adage that they cannot be true.

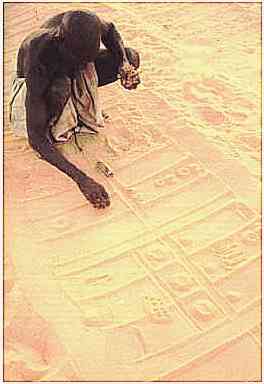

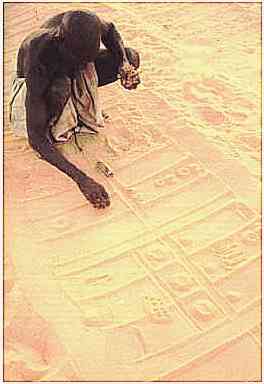

Born in the Netherlands (1947), I was trained at the university of my home town as an anthropologist specialising in religion. From my first fieldwork (1968), when I investigated saint worship and the ecstatic cult in rural North Africa, I have struggled with this problem — which I am inclined to consider as the central problem of interculturality. With gusto I sacrificed to the dead saints in their graves, danced along with the ecstatic dancers, experiences the beginning of mystical ecstasy myself, built an entire network of fictive kinsmen around. yet in my ethnography I reduced the very same people to numerical values in a quantitative analysis, and I knew o no better way to describe their religious representations than as the denial or North Atlantic or cosmopolitan natural science.[14] It was only twenty years later when, in the form of a novel (Een Buik Open — Opening a Belly — 1988) I found the words to testify to my love for and indulgence in the North African life forms which I had had to keep at a distance as an ethnographer; and my two-volume, English-language book manuscript on this research is still lying idly on a shelf. In the course of many years and several African fieldwork locations, always operating in the religious and the therapeutic domain, I gradually began to realise that I loathed the cynical professional attitude of anthropology, and that I had increasingly difficulty sustaining that attitude. Who was I that I could afford to make believe, to pretend, wherever the undivided serious commitment of my research participants was involved? Several among them have played a decisive role in my life, as examples, teachers, spiritual masters, lovers. In Guinea-Bissau, in 1983, I did not remain the observer of the oracular priests but I became their patient — like nearly all the born members of the local society were. In the town of Francistown, Botswana, from 1988, under circumstances which I have discussed at length elsewhere[15] — the usual for of fieldwork became so insupportable to me that I had to throw overboard all professional considerations. I became not only the patient of local diviner-priests (sangomas), but at the end of a long therapy course ended up as one of them, and thus as a believer in the local collective representations. At the time I primarily justified this as a political deed, fro me as a white man in an area which had been disrupted by white monopoly capitalism. Now more than then I realise that it was also and primarily an epistemological position taking — a revolt against the professional hypocrisy in which the hegemonic perspective of anthropology reveals itself. It was a position taking which in fact expelled me from cultural anthropology (although I did go by my own choice) and which created the conditions for the step which I finally made when occupying my present chair in intercultural philosophy.

This step means a liberation, not only from an empirical habitus which, along with existential distress, has also yielded me plenty of intellectual delight, adventure, and honours; but also liberation from such far-reaching spiritual dependence from my mentors and fellow cult members are originally characterised by sangoma-hood. Becoming a sangoma was a concrete, practical deed in answer to the contradictions of a practice of intercultural knowledge production which I had engaged in for decades, with increasing experience and success. Becoming an intercultural philosopher means a further step: one that amounts to integrating that deed in a systematic, reflective and intersubjective framework, in order to augment the anecdoctal, autobiographical ‘just so’ account with theoretical analysis, and to explore the social relevance of an individual experience. For what is at stake here is not merely an autobiographical anecdote. If I struggled with intercultural knowledge production, then my problem coincides with that of the modern world as a whole, where intercultural knowledge production constitutes one of the two or three greatest challenges. If it is possible for me to be at the same time a Botswana sangoma, a Dutch professor, husband and father, and an adoptive member of a Zambian royal family, while at the same time burdened by sacrificial obligations, cultural affinities and fictive kin relationships from North and West Africa, then this does not just say something, about me (a me that is tormented, post-modern, boundless, one who has lost his original home but found new physical and spiritual homes in Africa). Provided we take the appropriate distance and apply the appropriate analytical tools, it also says something about whatever ‘culture’ is and what it is not. It implies that culture is not bounded, not tied to a place, not unique but multiple, not impossible to combine, blend and transgress, not tied to a body, an ethnic group, a birth right. And it suggests that ultimately we are much better of as nomads between a plurality of cultures, than as self-imposed prisoners of a smug Eurocentrism.

So far for the argument from intercultural epistemology. The second point is much shorter. According to de Certeau (quoted in great approval by Mudimbe) religion is not only thwarted epistemology but also action by which an incredible belief is rendered credible:

‘The ambiguity of theological projects cannot but lead us back to an essential question: how can we comprehend the credibility of Christianity in the Third World? The late Michel de Certeau notes in The practice of everyday life (1984) that ‘‘the credibility of a discourse is what first makes believers act in accord with it. It produces practitioners. To make people believe is to make them act...etc.’’[16] ’[17]

Mudimbe uses this convincing line of thought with relation to missionary Christianity, which is unmistakably incredible for the agnostic that he repeatedly professes to be at this point in his life, and which he claims to have been at least since his 1968 days at Paris-Nanterre.[18] But why does Mudimbe allow this explanation to apply exclusively to Christianity in Africa, and not to African historic religion which is rendered credible in praxis in essentially the same way?

Meanwhile an alternative interpretation presents itself of Mudimbe’s presumed bone cancer, its being an illusion based on misdiagnosis, the explosion of creativity in all his genres of text production (poetry, novel, essay in the philosophy of science), and the subsequent disappearance of the symptoms. Described thus, we have an event rendered in the global language of medical rationality (which however misfired, in this case) and academic and literary book production. I would read the case very differently as an African diviner-priest with thirty years of experience in a cultural setting, the Nkoya people of Western Central Zambia, with strong cultural, migratory and linguistic links with the Luba people from Congo (with whom Mudimbe identifies on his mother’s side). In the cosmology of Central Africa, bones constitute of the ancestors’ coagulated sperm, which may be symbolised as white beads, or as the diviner’s bones on which diagnosis is based. Having converted lock, stock and barrel to an alien world-view, to clerical intellectualism of a global signature and North Atlantic orientation, Mudimbe’s ancestral heritage could be said to be dying — culturally in the sense that beyond the Luba and possibly Songye language he allowed hardly anything of the ancestral culture to remain part of his life, and physically in that his very bones were giving signs of literally decaying. However, that conversion was not an illusion but a fact, and it allowed him to tap — through the act of textual creation — such vital spiritual and physical resources at transformation and reconstruction of self, as were residing in another, at least equally powerful world-view, the one to which he had converted. And there the true miracle happened: the bone cancer which at one stage was not an illusion based on misdiagnosis, but a fact, was arrested by the creative transformation which Mudimbe unleashed in these five months, was had been alienation from an ancestral heritage until then had become an authentic source of life, and he survived to become the most successful, famous, profound and heroic representative of the new category of cultural converts which make up a sizeable proportion of today’s African intellectuals, a veritable métis.

If African historic religion is no longer the dominant cohesive social force in the urban and intellectual context of Kinshasa, Lubumbashi and other Congolese cities, this does not mean that such religion has entirely disappeared from the contemporary Congolese social life in the rural areas; recent ethnographic research by accomplished ethnographers like Devisch and de Boeck has demonstrated its continued vitality and viability.[19]

If African historic religion has succeeded to survive to some extent in the countryside of Central Africa, why is it far less conspicuous in the big cities? Like in Belgium, Roman Catholicism was something of a state religion in Belgian Congo, Rwanda and Burundi. This does not mean that there is a 100% overlap between the religious and the statal domain; for as Mudimbe acknowledges that the Central African colonies, like Belgium, had a certain plurality of European ideological expressions (Protestantism, Freemasonry, and one may add socialism) rival to Roman Catholicism, and some of them with rather disproportionately great power in national politics. However, the effect of the practical coinciding of state and world religion is a particular form of micropolitics, which has a direct bearing on the eclipse of religious alternatives to Roman Catholicism from public and even private life. There is a constant reinforcing between statal and religious sanctioning in the policing of citizen’s everyday life. The state, which in its twentieth century form is primarily a democratically legitimated oligarchy, assumes reality partly through the citizen’s submission to and veneration of the representations of the church; and the intangible sanctions of the church somehow receive a vicarious backing from the display of physical force (the prison, the police, the army) and the powerful bureaucratic procedures proper to the state. The Enlightenment rationality of the modern state nicely matches the verbose doctrinal rationalisations of Roman Catholic theology. The result of all this is that in the consciousness and practices of the citizens all heterodoxy tends to be shunned as criminal and as an act of national treason, by virtue of strongly internalised modes of assessment, self-control, and domestication. In everyday Belgian life especially outside the big cities, even Protestantism may be seen in this heterodox light, and so are certainly the expressions of ‘paganism’, be they European, African, or from a different extraction. (For that very same reason they also invite common fascination as expressions of defiance of a paternalistic, unaccountable, and increasingly inefficient state, as e.g. the Dutroux affair, the Nijvel gang, and even the middle- and upper-class appeal of Freemasonry would suggest). Heterodoxy instils the ordinary law-abiding citizen with a sense of horror and especially shame, comparable to the shame adults feel in cases of imperfect public concealment of their own bodily functions (signs of incontinence, of menstruation leaking through, etc.). In a system of evaluation along such axes as child versus adult, animal versus human, stupid versus intelligent, exclusion versus inclusion, punishment versus reward, heterodoxy thus installs itself on the negative end. Mudimbe is as good a guide as any critic of colonialism to identify these social pressures towards compliance with world-religion orthodoxy, but it is important to realise that these pressures are not limited to the colonial situation. They can still be seen to work in post-colonial African societies: among the citizens as a mode of acquiescence; while among the political elite the semi-secret semi-public display of heterodox horrors (for instance in the occasional display of violence, sorcery, and human sacrifice) reinforces such acquiescence, since these horrors are profoundly threatening to the citizens.[20] Therefore, in the public culture of Central Africa from at least the middle of the twentieth century if not earlier, much like in the public culture of Botswana, considerable sections of the population (especially the urbanites and middle classes) are effectively shielded off from African historic religion by an effective screen of internalised shame. In Zambia in the early 1970s I detected (as a youngerand less sensitive observer) nothing similar, but over the past thirty years I have seen the gradual installation of a precisely such a screen. Today this altered state of affairs occasionally makes me appear a social fool in that country, when unthinkingly I publicly mediate a historic African religious identity as someone who has obviously not permanently resided in the country recently, whose main Zambian identity was formed in of the rural areas of central western Zambia in the early 1970s when African historic religion was still a dominant idiom there, who subsequently became a diviner-priest in Botswana according to a religious idiom which meanwhile has gained considerable public currency in Zambia as well, and therefore as someone who does not always realise that it is no longer socially acceptable to mediate African historic religion in the public space of the town and the open road.

One may wonder why Mudimbe should stop, like he does, at the evocation of the few heroes and saints of the cultural mutant order of clerical intellectualism (Kagame, Kizerbo, Mulago, Mveng), and not trace the installation of that mutant order throughout Central African society in the second half of the twentieth century. With the general spread of formal education (however low its level), and the prominence of clerical intellectuals in the educational system, the main conditions were set for the percolation of (admittedly: attenuated, compromised, versions of) this mutant order far outside the seminaries, convents and universities where it was originally engendered, to become, perhaps, a standard cultural orientation among tens, possibly hundreds of thousand of people of the urban middle class in Central Africa. Did this happen? If it did, how did this influence the political and religious itinerary of the societies of Congo, Rwanda and Burundi in the second half of the twentieth century? If it did, how did it help to explain Mobutuism, its politics of authenticity (which, much like clerical intellectualism, amounted to a virtualisation and thus effectively an annihilation of historical African cultural and religion), the specific form of proliferation of church organisations which took place in Congo, and the general emergence of a contemporary social order in which Christianity and literacy have become the norm, and African historic religion has been eclipsed or at best has gone underground, mainly to emerge in highly selective and virtualised form in certain practices of African Independent churches. Is perhaps the violence (more specifically the death) which forms the refrain of Mudimbe’s spiritual itinerary, and which I am inclined to interpret as the murder on African historic religion, akin to the extreme and extremely massive violence which has swept Congo, Burundi and Rwanda throughout the second half of the twentieth century? Anthropologists like Devisch and de Lame have struggled with the interpretation of the latter form of violence in Central Africa,[21] and their sociological interpretations, while adding a social scientific dimension to the psychoanalytical and philosophical hermeneutics of Mudimbe, certainly do ring somewhat naive in the light of Mudimbe’s essayistic philosophising, although the latter does lack sociological imagination and manifests the literature scholar’s disinclination to think in terms of large-scale social categories and their institutions.

This means that we might yet take seriously Mudimbe’s claim that Tales of faith is about any post-colonial individual,[22] and not just about himself and a handful of fellow clerical and post-clerical intellectuals from Central Africa. Despite his exceptional erudition, cosmopolitan orientation, and success, Mudimbe’s predicament is to a considerable extent that of the contemporary Central African middle classes in general. A glimpse of what lies at today’s far end of the itinerary that started with Kagame c.s., may be gathered from the following impression, which I owe entirely to the ongoing Ph.D. research of Julie Duran-Ndaya:

‘In July, 2000, Kinshasa was the scene of a major church conference of the Combat Spirituel (Spiritual Combat) movement. The conference involved close to 20,000 people, many of whom have travelled to Kinshasa from western Europe and other places of the Congolese diaspora. Obviously we are dealing here with a highly significant social phenomenon at a massive scale. The movement caters for upper middle class and professional people, especially women. Women also play leading roles in the movement’s organisation. The movement’s doctrine and ritual combine an original re-reading of the Bible with techniques of self-discovery and self-realisation under the direction of female leaders. The spiritual battle which members have to engage is, is a struggle for self-realisation in the face of any kind of negations or repressions of personal identity, especially such as are often the fate of ambitious middle-class women in diasporic situations. In order to achieve this desired self-realisation, it is imperative that all existing ties with the past, as embodied in the traditional cultural norms of historic Central African society, and as represented by the ancestors, are literally trampled underfoot. Thus a major part of regular church ritual is to go through the motions of vomiting upon evocations of the ancestors, and of violently and repeatedly stamping on their representations. The catharsis which this is to bring about is supposed to prepare one for the modern, hostile world. Some members experience very great difficulty in thus having to violently exorcise figures and symbols of authority and identity which even in the diffuse, virtualised kinship structure of urban Congolese society today have been held in considerable respect. But while this predicament suggests at least some resilience of historic African religion (otherwise there would be no hesitation at tramspling the past and the ancetors), it is practically impossible for diasporic Congolese to tap, for further spiritual guidance, the resources of historic African religion in the form of divination, therapy and protective medicine: not one reliable and qualified Congolese specialist in historic African religion (nganga) is to be found in, for instance, The Netherlands or Belgium.’[23]

The make-up of this topical situation is reminiscent of that of the clerical intellectual mutation half a century ago: the literate and Christian format appropriated as self-evident yet subjected to personal selective transformation, the rejection of an ancestral past and of African traditional religion, the total inability to derive any spiritual resources from the latter, and the effect of being propelled into a mutant cosmopolitan cultural and spiritual solution which is African by the adherent original geography and biology, but not in substance.

Proceed to:

Part 0. Introduction and links to

other parts

Part 1. Mudimbe's method

Part 2. Clerical

intellectualism in Central Africa

Part 3a. Mudimbe's homelessness: No African home,

Afrocentrism, death

Part 3b. Mudimbe's homelessness: plurality of African

cultures; death; métissité

Part 5. Conclusion: Mudimbe's and van

Binsbergen's itineraries compared

[1] Kagame, A., 1955 [ 1956 ] , La philosophie bantu-rwandaise de l’Être, Bruxelles: Académie royale des Sciences coloniales.

[2] Elsewhere in the same book Mudimbe is to declare his ‘indebtedness to Willy Bal. Thirty years ago, he taught me how to read a text with a philologist’s eye, and later on, at Louvain, he patiently introduced me to the art of reading as a demanding undertaking.’ Mudimbe, Parables and fables, p. xxii. Cf. Bal, W., 1963, Le royaume du Congo aux XVe et XVIe siècles: Documents d’histoire, Léopoldville: Institut National d’Etudes Politiques.

[3] Mudimbe, Parables and fables, pp. 124-125; part of the same quotation was used in a footnote above when Mudimbe’s claim to ethnographic authority was presented.

[4] Davidson, B., [ year ] , Mother Africa, [ place: publisher ] ; ben-Jochanan, Y.A.A., 1988, Africa, Mother of Western Civilization, Baltimore : Alkebu-lan Books/Black Classic Press, first published 1971.

[5] Mudimbe, V.Y., 1988, The invention of Africa: Gnosis, philosophy, and the order of knowledge, Bloomington & Indianapolis: Indiana University Press/London: Currey; Mudimbe, V.Y., 1994, The Idea of Africa, Bloomington & London: Indiana University Press.

[6] Berlinerblau, Heresy, o.c.; Fauvelle-Aymar, F.-X., Chrétien, J.-P., & Perrot, C.-H., 2000, eds., Afrocentrismes: L’histoire des Africains entre Égypte et Amérique, Paris: Karthala; Howe, Stephen, 1999, Afrocentrism: Mythical pasts and imagined homes, London/New York: Verso, first published 1998. My review article around the first book is forthcoming in Journal of African History, I have a contribution on the Black Athena debate in the second book, and defended Afrocentrism against the third book in: ‘Le point de vue de Wim van Binsbergen’, o.c.

[7] Tales, p. 176.

[8] Tales, p. 25.

[9] Tales, p. 16; the same point is taken up again in detail p. 159f. What this really says is that European text on African religion will always be alien and alienating.

[10] Tales, pp. 76f.

[11] Tales, p. 80.

[12] Tales, p. 82.

[13] Winch, P., 1970, The Idea of a Social Science and Its Relation to Philosophy, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, first published 1958, p. 100f; Sogolo, G.S., 1993, Foundations of African philosophy, Ibadan: Ibadan University Press; Jarvie, I.C., 1972, Concepts and society, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

[14] van Binsbergen, W.M.J., 1985, ‘The historical interpretation of myth in the context of popular Islam’ in: van Binsbergen, W.M.J., & Schoffeleers, J.M., 1985, Theoretical explorations in African religion, London/Boston: Kegan Paul, pp. 189-224; van Binsbergen, W.M.J., 1980, ‘Popular and formal Islam, and supralocal relations: The highlands of northwestern Tunisia, 1800-1970’, Middle Eastern Studies (London), 16, 1: 71-91; van Binsbergen, W.M.J., 1985, ‘The cult of saints in North-Western Tunisia: an analysis of contemporary pilgrimage structures’, in: E. A. Gellner, ed., Islamic dilemmas: reformers, nationalists and industrialization. The Southern shore of the Mediterranean, Berlin, New York, Amsterdam: Mouton, pp. 199-239.

[15] van Binsbergen, W.M.J., 1991, ‘Becoming a sangoma: Religious anthropological field-work in Francistown, Botswana’, Journal of Religion in Africa, 21, 4: 309-344, also available at http://come.to/african_religion; van Binsbergen, W.M.J., 1998, ‘Sangoma in Nederland: Over integriteit in interculturele bemiddeling’, in: Elias, M., & Reis, R., eds., Getuigen ondanks zichzelf: Voor Jan-Matthijs Schoffeleers bij zijn zeventigste verjaardag, Maastricht: Shaker, pp. 1-29; English version: Sangoma in the Netherlands: On integrity in intercultural mediation, at: http://come.to/african_religion .

[16] De Certeau, M., 1984, The Practice of Everyday Life. Berkeley: University of California Press, p. 148.

[17] Tales, pp. 82f.

[18] ‘At Nanterre (...) I did not hide the fact that I was then a practicing Catholic, although, philosophically, agnostic.’ Mudimbe, Parables and fables, p. ix. He can hardly have been an agnostic when he stayed at the Catholic seminary of Mwere near Lubuimbasi in the early 1960s, or when he entered a Rwandan Benedictine convent as a novice, but from the latter he soon resigned (Tales, p. 137; Mudimbe, Parables and fables, p. 125: ‘my brief sojourn’.

[19] de Boeck, F., 1991a, ‘From knots to web: Fertility, life-transmission, health and well-being among the Aluund of southwest Zaire’, academisch proefschrift, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven; De Boeck F. and R. Devisch, 1994 Ndembu, Luunda and Yaka divination compared: From representation and social engineering to embodiment and world-making. Journal of religion in Africa 24:98-133; Devisch, R., 1984, Se recréer femme: Manipulation sémantique d’une situation d’infécondité chez les Yaka, Berlin: Reimer; Devisch, R., 1986, ‘Marge, marginalisation et liminalité: Le sorcier et le devin dans la culture Yaka au Zaïre’, Anthropologie et Sociétés, 10, 2: 117-37; Devisch, R., , 1991 Mediumistic divination among the Northern Yaka of Zaire: etiology and ways of knowing. In P. Peek (ed.), African divination systems: ways of knowing. Bloomington: Indiana university press 104-123; Devisch, R., & Brodeur, C., 1999, The law of the lifegivers: The domestication of desire, Amsterdam etc.: Harwood.

[20] Toulabor, C., 2000, ‘Sacrifices humains et politique: quelques exemples contemporains en Afrique,’, in: Konings, P., van Binsbergen, W.M.J., & Hesseling, G., eds., Trajectoirs de libération en Afrique contemporaine, pp. 211-226.

[21] Devisch, R., , 1996 ‘Pillaging Jesus’: healing churches and the villagisation of Kinshasa. Africa 66:555-586; Devisch, R., , 1995 Frenzy, violence, and ethical renewal in Kinshasa. Public culture 7:593-629; de Lame, D., 1996, Une colline entre mille: Le calme avant la tempête: Transformations et blocages du Rwanda rural, Ph.D. thesis, Free University, Amsterdam; published by Tervuren: Musée Royale de l’Afrique Centrale.

[22] Tales, p. 198.

[23] This passage based on Duran-Ndaya, J., 1999, Rapport de recherche provisionnel, Leiden: African Studies Centre, internal report. I am grateful for the many discussions I had with Mrs Duran-Ndaya on her fascinating ongoing Ph.D. research.

Proceed to:

Part 0. Introduction and links to

other parts

Part 1. Mudimbe's method

Part 2. Clerical

intellectualism in Central Africa

Part 3a. Mudimbe's homelessness: No African home,

Afrocentrism, death

Part 3b. Mudimbe's homelessness: plurality of African

cultures; death; métissité

Part 5. Conclusion: Mudimbe's and van

Binsbergen's itineraries compared

| page last modified: 05-02-01 20:12:50 |  |

|