RECONCILIATION

A major African social technology of shared and recognised humanity (ubuntu)

Wim van Binsbergen

|

RECONCILIATION A major African social technology of shared and recognised humanity (ubuntu) Wim van Binsbergen |

|

INTRODUCTION1

From the Jewish-Christian orientation of North Atlantic culture, a specific, and valuable interpretation has been given to the concept of reconciliation. Yet reconciliation is very far from primarily or exclusively a Christian concept. The society of Israel in the late second and in the first millennium of the North Atlantic era reflected, in its social organisation, in many respect the societies of other Semitic-speaking peoples and of the Ancient Near East in general. The patterns of conflict settlement which have been sanctified in the Jewish-Christian tradition have more or less secular parallels in the Near East and North Africa. I would go even further and claim that reconciliation is an essential aspect of all human relationships, both in primary human relations based on face to face interaction, and in groups relationships of a political, religious and ethnic nature, which encompass a large number of people. Like in the theological conception of reconciliation, in many societies' religion the theme of interpersonal reconciliation is complemented by that of the reconciliation between man and god by mean of ritual, prayer and sacrifice -- the familiar pattern also in Christianity.

In this paper I intend to present a preliminary anthropological reflection on reconciliation. For this purpose, the data have to be gleaned from various sections of cultural anthropology, for a cultural anthropology of reconciliation a such does not yet exist. I have primarily derived my inspiration from my own researches in the course of a considerable number of years in various parts of Africa south of the Sahara and in north Africa, in the field of group processes in small-scale social contexts, and on the role of ritual, therapy and litigation in those contexts.

The self-evident attention of social scientists, especially of anthropologists, for processes of social accommodation, conflict regulation, reconciliation, in mall-scale social context means that many of us have been researching reconciliation, along with the related topics, from a comparative angle without deeming it necessary to establish a formal anthropology of reconciliation. Some forty years ago such pioneers as Max Gluckman and Louis Coser had to realise that the obsession with regulation, integration, consensus and institutionalisation, under the then dominant paradigm of structural functionalism, had prevented the young social sciences from developing a sub-discipline which yet would have come so close to everyday experience: the study of social conflict. The preoccupation with processes of reconciliation as an implicit anthropological field of study has become possible by a fundamental shift which occurred in anthropology in the middle of the twentieth century, especially on the initiative of Max Gluckman. Because of that shift, the study of institutions ('society as a fixed scenario which is faithfully acted out by the actors, who in themselves are mutually replaceable') gave way to the extended case method: society as the resultant of the historicity of micro-political process. Meanwhile extended case research has developed into a very subtle and widely used anthropological tool. Following the increasing presence of violence in small-scale and large-scale social and political situations anywhere in the world including North Atlantic society,, we have seen during the last on and a half decade the emergence of a social science of violence. It is time for an anthropology of reconciliation. This not only reflects the increasing violence inflicted by national states, ethnic groups, citizens, men and women, elders and youth, upon themselves and each other; but also the context of massive socio-political movements forced to think in broader and more forward-looking term than just violence alone: the formation of the European Union half a century after the most comprehensive and most disruptive war which Europe has ever known; the incorporation of the massive influx, again unprecedented in history, of intercontinental immigrants, with their own somatic, cultural and religious specificity; and the contemporary experience of being swamped in information of large and terrible conflict elsewhere in the world, and on north Atlantic interventions, even initiatives, in those conflicts.

Given my specific expertise I opt to choose as the perspective of my argument not the macro-reconciliation of large social groups in the context of civil war, ethnic war and genocide, which Africa has seen so abundantly in the course of the last few decades of the twentieth century; in stead I shall explore the micro presses which take place at the level of the village society, or of a group of neighbour within an urban quarter.

In order to avoid misunderstanding -- given the fact that much of the discussion on reconciliation appears to be inspired from a theological corner -- it is good to remind ourselves that in cultural anthropology, as an empirical field of study, we tend to make a number of reservations and tend to limit ourselves to a rather narrow selection from human reality. Both fieldwork van the final ordering and interpretation of ethnographic data require a considerable amount of creativity, empathy and intercultural intersubjectivity on the part of the anthropologist. Yet strictly speaking we have no other source of knowledge than the overt behaviour of people. Also the pronouncements individuals make concerning the normative and symbolic systems of their society and culture, are in the first instance mere verbal behaviour. As anthropologists we are intimately used to the contradictions such as exist within individuals, groups, and within entire societies; and we realise that all forms of overt behaviour, and all identities and norms which individuals and groups mediate through overt behaviour, have a situational nature. Therefore as anthropologists we are not greatly assisted by such terms as 'sincerity', 'intention', and the like. For such terms suggest that we (like the God of the theologians, whose perspective the theologians themselves appear to adopt) are capable of looking directly into the heart of people. For anthropologists, such concepts have only meaning as collective and publicly mediated cultural ideals, by reference to which the behaviour of individual actors is being assessed and around which multi--layers compromises and performances are wrapped of the kinds typical of any human social behaviour. This is not to say that for anthropologists any social and cultural utterance is entirely devoid of purity; we are able to gauge, to a certain extent, people’s struggle with purity and sincerity as defined within their culture, but their sincerity in itself is not a useful anthropological datum. Therefore for us a anthropologists it is much more difficult to define, of all thing, 'true reconciliation', than it is for theologians.

AN ATTEMPT TO DEFINE RECONCILIATION

In the first place it should be clear that a necessary condition for reconciliation is the following: the express recognition by the parties concerned, that there is an specific, explicitly expressed conflict. This is less self-evident than it appears. Many conflicts and oppositions in society are partially implicit and partially concealed from the actors' consciousness. Many overt conflicts no not in fact revolve on the stakes which are apparently being mediated, but about underlying stakes which remain partially unexpressed and which are unclear to at least a part of the combating actors. Reconciliation is only possible if the conflict is clearly and publicly discussed by those involved, and such discussion creates a clarity which may well have a beneficial influence on future relations, also because previously unexpressed contradictions have found an overt formulation which allows them to be taken into account much more readily in the social process.

Moreover, reconciliation is a creative social act of rearrangement and reinterpretation. This must be understood in the following sense: if available legal rules would have been self evidently and simply applicable to the case, the conflict would not have occurred and there would have been no question of reconciliation. Probably reconciliation is always the recognition that firm rules are not sufficient. Dropping those rules therefore is an acknowledgement of shared humanity (ubuntu!) and therefore creates the central condition for community, for society. This means that reconciliation is perpendicular to the normative, the institutionalised: it is the additional cohesion which make community and society possible. In this way reconciliation even constitutes society. Hence also the fact that a confession of guilt need certainly not always be a condition for reconciliation, or a necessary part of, reconciliation.

Reconciliation therefore is not o much the alternative to conflict, but the transformation of conflict, and one which makes it possible both to clearly define the stakes of the conflict and to relativise these stakes in the light of a larger good, pointing towards the future and towards a wider community than just the parties involved in the conflict.

Reconciliation is emphatically not the application of formal normative rules from a society’s cultural orientation, it is not the result of a fixed procedure or a fixed scenario, but it consists in the creation of a framework within which those rules can acquire an added value of inclusivity, flexibility, transcendence.

In this process it transpires whatever people feel to be the most fundamental basis of their social life. This can be many different things, for instance:

- the recognition of a shared humanity; then reconciliation implicitly implies that a particular conception of the human person is being mediated (ubuntu!)

- the recognition of the need to terminate the conflict in the interest of a future generations

- recognition of a shared identity and responsibility vis-a-vis the supernatural.

These themes do not in the least rule out an element of elf-interest in bringing about, and accepting, reconciliation. Probably on this point the anthropological discourse on reconciliation takes a distance from the theological discourse, which centres on integrity and authenticity.

The shared humanity which is found back, and expressed, in reconciliation, also makes possible again other forms of contact, which in their turn foreshadow future possibilities of reconciliation. If the reproduction of society to a large extent takes place by means of reconciliation between groups, then it stands to reason that other reproductive elements may serve as an expression of such reconciliation as is being reached. Much reconciliation is accompanied by the consumption of food and drink, for these are conditions for the maintenance and the reproduction of the human body. Collective consumption in this manner is an expression of the same shared humanity which is being implied in reconciliation.

On both sides of the Mediterranean massive annual festivals of saints display such commensality to a great extent. In practice they constitute a calendrical event of reconciliation in the midst of a year full of violence or the threat of violence between various villages, clans etc.,, which however during the annual festival have sanctuary to visit as pilgrims, i.e. in an explicitly ritual context.

Also here we see an element of biological reproduction as an extension of the shared humanity as emphasised in reconciliation. Such annual festivals are, among other things, informal marriage markets. And in general, in a large number of contexts the world over reconciliation is symbolised by engaging in marital relations. As the Mae Enga of New Guinea put it (a society of the segmentary type such as we shall discuss below): ‘We marry the people we fight’. Also a specifically sexual expression of reconciliation is possible, as is borne out e.g. in the numerous accounts and myths featuring royal marriages between the victors and the vanquished.

Moreover reconciliation revolves on the explicit verbalisation of the termination of a conflict. Such verbalisation is often public, and often it depends on the intercession of a third party in the role of mediator. Reconciliation is usually a public event, and important forms of social control derive from the public confession of a state of reconciliation.

However frequent though, neither the public nature of reconciliation nor the intercession of mediator is a universal given.

Not always mediators. AN oath, such as accompanies many contexts of reconciliation in North Western Africa, may appeal to invisible supernatural agents, in such a way that formally n intercession of mediating humans is necessary.

In North Africa the collective oath is a central mechanism of reconciliation. One takes an oath by reference to a supernatural power (God, or the grave of a local saint). This invokes a super-human sanction in case the sworn statement which is capable o terminating the conflict, might turn out to be false, or not to be observed (if it is a promise). Meanwhile such oaths are usually made before outsiders invested with religious powers: marabouts, who are no party to the conflict and who -- through a peaceful way of life, and their abstention from weapons and violence -- have situated themselves outside the dynamics of secular lives. By contrast, ordinary life in that part of the world has tended to consist in a continuous struggle over ecologically scarce good (land, water, cattle, trading routes), and over person (women, children, subjects, slaves). Incidentally these peaceful marabouts, who through their association with saints’ graves which are fixed in the landscape have a special link with the land, is closely related, both systematically and -- probably -- historically, to the earth priests and oracular priests of West Africa, to the leopard skin chiefs of East Africa, t the oracular priests and heralds of Ancient Greece, Italy and the Germanic cultures; the theme of the herald’ staff and of the Hermes-like mediator is widespread throughout the Old World.

Not always public. However, different types of borderline situations can be conceived as far a the public and mediating aspects of reconciliation, The conflict may occur in such an intimate sphere that the admission of outside mediators involves great embarrassment if not shame -- this often applies to the conflicts between kinsmen, which one tends to see through in one’s own circle as long a this is still possible. The background of the Zambian case material which I would have discussed below if time had allow this, is that it is indecent to summon a close kinsmen to court -- and this of course applies in many societies, including our own. Much reconciling and therapeutic ritual is in fact private.

There are several types of reconciliation There is the reconciliation which although publicly confessed allows the conflict to simmer on, and as a result at least one of the parties involved still seeks a genuine termination of conflict through the effective annihilation of the adversary. Then again there is the reconciliation which does constitute a total transformation of social relations in a way which may closely approach the Christian theological definition of reconciliation. The latter type of reconciliation cannot merely be described in terms of law and power politics. It involves nothing less than man’s fundamental capability of creating a society out of symbols, and of dynamically guarding and adapting these symbols. The shared humanity which underlies any successful reconciliation does not only resolve the specific conflict which was at hand, but also inspires the people involved to embrace the social in many if not all other contexts in which they may find themselves. It produces a purification (catharsis). However, the extent and the duration of such catharsis depend large on the social structure obtaining in that time and place.

In reconciliation, not only society in general constitutes itself, but also the component conflicting group constitute themselves in the process. We should not think of social groups as firm persistent givens, which may happen or not happen to be engaged in a particular conflict. Many groups have no previous existence before the form themselves in the very context of conflict, through mobilisation and through the identification in terms of the stakes of the conflict, and the role this defines both during the conflict and in the reconciliation process. Part of this process is that the conflict is being explicitly verbalised, as mentioned above; it is then that also the conflicting groups need to have a name, a label, an identity. In Central African villages even the following situation obtains: any individual has a considerable number of possible group memberships at the same time (of a number of villages, a number of clans), and it is only in concrete situations of conflict and reconciliation, hen the social process intensifies, that one commits oneself, temporarily, to one specific group membership, allowing this to define who one is, which side one is on, and what one hope to get out of the conflict.

the role of the mediating outsider

In order to be able to play the role of mediator special characteristics may be needed. Usually the mediators are not themselves party to the conflict. If they are party in one respect, one is likely to find that in another respect they are in between both parties, for instance as political leader of a group comprising both conflicting parties, or as kinsman of one party but as affines (kinsmen through marriage) of the other party; we shall come back to this. High status brings to the mediator authority and also protection, and this he may need for as long as the conflict has not terminated intercession may not be without risk, certainly not if the conflict in question involves physical violence. Also a religious status (as prophet, saint, scriptural specialist, priest, may also confer authority and supernatural protection: the marabout, the griot (West African bard), the priest, the herald, who implicitly or explicitly are under the protection of extra-social forces and thence are in a position to effect reconciliation in the lives of others. Also class differences may be expressed in the role of mediator: in many societies a high social position means, in the first place, the responsibility, the duty, but also the right, to bring about reconciliation in others; hence the politician or the boss is often the chairman and initiator o informal palavers, a so is the African village headman.

the social costs and benefits of reconciliation

The great benefit of reconciliation consists in the fact that society is newly constituted, not only on the concrete basis of the regained unity of parties before at daggers drawn, but also on a much more general and abstract level: the reconstitution of any social community in term of shared humanity -- the confession of such shared humanity (ubuntu) is the essence of reconciliation. It creates the conditions to arrange the concrete practical detail of the conflict, once terminated, on a basis of trust. But against this social benefit, what is the price of reconciliation? To resign from a conflict that one has once started, may not be totally advantageous. The formal normative structure of the local society may stress peacefulness or it may stress prowess, and depending on that context the termination of conflict may be either honourable or shameful, it may be interpreted as a sign of strength or of weakness. To the extent to which conflict and the reconciliation which may follow conflict, have a public nature outside the narrow circle of the parties immediately involved, to that extent any reconciliation will have a social price, positive or negative, or a mixture of both in a plurality of aspects. But reconciliation will have a price also in the case of a conflict which is not public but which is fought out in the inner rooms of a kin group, or other face to face relationships. On the one hand both parties are being glorified by the ritual, abstract, sharing of humanity which is being testified in reconciliation. But on the other hand the manifest readiness to accept reconciliation, may undermine the credibility of either party in each other’s eyes and in the eyes of outsiders; this will particularly be the case in a context here confrontation and conflict are the everyday norm -- like in a segmentary society, or in the world of organised crime, in the context of economic competition in general, or in a bad marriage. Below we shall meet another possible price of reconciliation: pent up powerlessness, in a situation where the socially weaker party, in the interest of socially testified harmony, is left no choice but to resign in a public reconciliation (e.g. in the context of formal adjudication), even though the underlying problem is very far from finished in personal experience.

the symbolic technology of reconciliation

We have seen that it is not enough, in order to reach reconciliation, to bring to the fore the overtly available cultural contents of the situation, such as it is manifest and self-evident to all actors involved. The very existence of the conflict points in the direction of a contradiction in the social process: positions exists side by side which are each admissible in terms of the culture and of the system of social control, yet these positions are mutually irreconcilable. For the party occupying a particular position, that position is eminently valid; but the same applies to the other party. Clearly social systems do not work in the same way as the axiomatic systems of symbolic logic and of mathematics: it is common for social systems (as it is for biological systems) to arrive at the same point from different starting points, along different routes, and to invest that point with the conflicting tendencies between the various point of departure. Contradiction is an inevitable and necessary condition of social life; and utopias in which such contradictions have been reduced to a minimum, or have been annihilated altogether, will be unliveable states of terror. Given such contradictions, it is not enough to summon to the fore what is already understood to be self-evident in the local society; instead, one has to appeal, relatively and selectively, to implicit possibilities which lie hidden in the culture and society. If one does not immediately succeed in making an effective (i.e. conflict terminating, actually reconciling) selection from this shared pool of cultural material, then the mediator has to publicly reformulate, to publicly transform, the conflict, as well as the underlying social and cultural material, in such a way. in the course of his attempts at reconciliation, that it yet becomes possible, in the end, to come closer to one another and to confess publicly to this rapprochement.

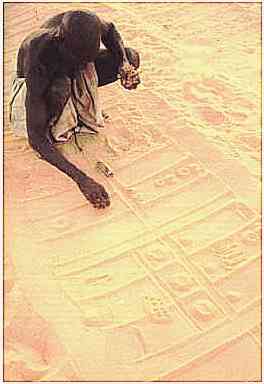

Here we hit on one of the paradoxes of reconciliation. Although reconciliation (at any rate, in the African societies which have inspired my argument) is perpendicular to institutionalised frameworks and procedures in the society, yet reconciliation is unthinkable without all parties concerned recognising a shared basis of communality, something on which they agree. This basis need not be a totally explicit given from the very beginning of conflict and reconciliation on. It is precisely ritual which enables us to produce, in preparation of reconciliation, points of view and bases for communality which so far had not been perceived consciously by the parties involves in the conflict. It is especially the task of the outsider who monitors and presides over the process of reconciliation, to identify, visualise, and exploit for the ultimate good, such hitherto unsuspected, hidden potential bases for communality. Especially African healers/diviners, whose task it is to bring out interpersonal conflicts and guide them towards reconciliation, tend to be masters in what we could all praxeological bricolage. By means of ‘do-it-yourself’ (French: bricolage), they construct a temporary, improvised language of communality, which was not felt to be present before the session started but which is the result of the verbal and non-verbal exchanges during the session, under the guidance of the therapist. And the latter is capable of bringing this about by means of the free use and the free re-interpretation of selected symbolic material which strictly speaking is available within the local cultural orientation but not exactly in that specific form in which it is summoned up in the divinatory and therapeutic session.

reconciliation and time

The time dimension of reconciliation appears to be of the greatest importance.

Reconciliation has the character of a process but also of a moment. The ritual of reconciliation is of a condensed nature, both in space and in time. If the conflict involves large sets of people (e.g. ethnic groups, nations, creeds) typically only a selection of the members of the groups involved directly participate in the reconciliation process. Reconciliation makes it possible to arrive at a specific transformation of the conflictive matter, which may then lead, in a much more diffuse way, to the reorientation of the everyday life of all group members concerned. Recnciliation therefore does not only mean the transformation of conflictive matter, but also indicating the possibilities for the transfer between reconciliatory ritual to everyday life to take place.

But not only need we make a distinction between reconciliation as a process (the terminal phase of a conflict which has already run a considerable course through time), and reconciliation as the concrete moment when the viewpoint informing both conflict and reconciliation are particularly clearly expressed and the parties in conflict and reconciliation concretely constitute themselves. It is more important that reconciliation is in itself a thinking about time: the normal time, when conflict is taken for granted, is interrupted, and it makes place for an ideal time, one of reconstruction, purity, clarity, sociability, in which the conflict is no longer capable of occurring, and that moment looks forward to the future, in which the transformation implied by reconciliation, will -- ideally -- have caused the then normal time to have inclined towards ideal time. Even when reconciliation does not last and new conflict will continue to present itself in future, yet this reordering of time is the central idea of such transformation as is implied in recnciliation. In reconciliation eternity simmers through, in a way which -- without Christian inspiration -- occurs in African, Asian, Latin American and Oceanic societies jut as well as in North Atlantic ones under the inspiration of the Christian theory of reconciliation; yet that theology may be recognised as an impressive, classic expression of what is now gradually expressed as the emerging anthropology of reconciliation.

Another temporal dimension of reconciliation has to do with its possibly cyclic nature. In many African societies reconciliatory events are not so much unique, one for all, but repetitive and circular. This is what Calmettes points out in the context of the cyclical nature of witchcraft eradication movements in the village of Northern Zambia: these invariably occurred in a cycle of crises one every 10-15 years. In my view this cycle was produced by a combination of ecological and demographic factors causing periodic unbearable strain on the local community’s natural and leadership resources. Reconciliation is then one of the predictable phases in the social process of the small-sale local community, in a continuous pendulum swing movement back and forth between the following positions:

-- after which the cycle is repeated unless reconciliation proves impossible and the community (village, kin group, congregation, political party) falls apart.

IN segmentary, acephalous societies (see below) this repetitive nature is not even distributed across time. There reconciliation and conflict occur simultaneously depending on the constantly shifting, kaleidoscopic, segmentary perspective within which an actor in such societies has situated himself vis-a-vis all other actors.

In those African societies which have an elaborate political system organised around a chief or king, the cyclic nature of reconciliation goes through a development along with the person of the king himself. As long as the king is alive and well, a condition prevails according to which the political system, the human society in general, he land, the crops, game, the rain, the cosmos in its totality, know the greatest regularity and fertility. However at the king’s death -- already when it is still imminent -- an interregnum begins during which both the political, the social and the cosmic order is supposed to be fundamentally disturbed, so that illness and drought, infertility, conflict, violence, incest and sorcery may reign supreme. This state can only be brought to an end by the accession of a successor, who brings about the reconciliation, both politically, socially and cosmically, through which chaos is turned once more into order.

Conflict, revenge, feud, sorcery are the opposites of reconciliation and it is to these alternatives that I shall return towards the end of my argument.

RECONCILIATION AND SOCIO-POLITICAL ORGANISATRION: SEGMENTARITY AND FEUD

One of the principal contexts in which the problematic of reconciliation has come to the fore in anthropology is that of the feud and if the structure of acephalous societies -- those in which feud is a characteristic per excellence. Evans-Pritchard -- in his description of the East African Nuer, an acephalous society, defines the feud as follows:

‘lengthy mutual hostility between local communities within a tribe’, Evans-Pritchard 1940: 150.2

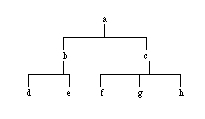

In Evans-Pritchard’s analysis, the entire (or rather, the entire male) social structure presents itself as a consistently executive tree diagram (dendrogram), whose humblest, smallest twigs are formed by the individual members, united at the nodes into groups of brothers, the latter in their turn united at higher-order nodes into groups of cousins, groups of cousins in their turn into even larger groups, into still larger groups, into yet larger groups... until finally, at least in theory, the dendrogram encompasses the entire society. The branches of the dendrogram make both for integration (for all twins under the same node constitute a united group), and for opposition at the same time: for the nodes at the same level, although united in their turn by a higher-order node at the next level, are still in opposition vis-a-vis one another, and in fact this also applies to all groups and individuals tied to each other by the node immediately above them. For this type of structure anthropology has coined the term of ‘segmentary system’. According to Evans-Pritchard, Nuer society (and as such it was alleged to be representative of many other societies both in Africa and outside) hangs together by the subtle play between segmentary opposition and integration, both of which always present themselves in complementarity depending on the perspective which the actor takes. n theory we an tell exactly where this structure meets its boundary: there were segmentary integration at the highest level is still possible because of the possibility of reconciliation after violence.

Diagram 1. A simple segmentary system of segmentation

‘d’ and ‘e’ are is segmentary opposition vis-a-vis one another, but they are in segmentary integration as parts of ‘b’ by opposition to ‘f’, ‘g’, ‘h’ respectively ‘c’; etc.

If it turns out that such reconciliation is not possible and that only violence an answer previous violence, then obviously the segmentary distance has become too large, and one has left the horizon of one’s own society.

In Nuer society conflicts are the order of the day, and they are usually accompanied by physical violence. In the case of violent conflict within the village, one takes precautions so as to prevent a mortal outcome (choice of weapons), but between different villages manslaughter does occur.

There is a moral obligation to settle conflicts through mediation, thus effecting reconciliation instead of retaliation. On the other hand one of the pillars of the lineage organisation is the obligation to revenge the murder of an agnate (a patrilineal kinsmen). This is a typical social contradiction, which cannot be resolved by normative or judicial means, but only through a process of reconciliation which transcends such institutional means. The function of the leopard skin headman and his mediation makes it possible to alleviate these contradictory tendencies and to bring about reconciliation in the place of feud. These headmen (Nuer society is alleged to know no other hypes of headmen) have no effective material or military power, no great authority, but they do have A special link with the Earth, by virtue of which they may curse people. After killing a person the perpetrator flees to the headman and as long he is in the latter’s sanctuary, he cannot be killed. The victim’s kinsmen lie in ambush in case the murderer ventures outside his sanctuary. Meanwhile the headman ritually cleanses the killer (on is reminded of the Oresteia and dozens of other similar passages in Ancient Greek tragedy). At the same time he sets in motion a process of reconciliation: exhortations to forgiveness, and negotiations about the number of heads of cattle which the murderer’s kinsmen are to pay. If this is settled after a few weeks, the murderer an return home and although a general unease lingers on, no counter-murder will be committed.

Evans-Pritchard stresses that the larger the social distance (i.e. the segmentary distance, as measured along the elements of the dendrogram) between the social groups involved, the smaller the chance that the conflict may be settled in this way. Feud characterises the relationships between distant groups, whereas between closely neighbouring villages which (by virtue of their proximity) share all sorts of ecological interests, for that very reason the conflict cannot be allowed to persist in its original violent form, and reconciliation is imperative.

alternative interpretations of the reconciliation process among the Nuer

On this point the Manchester School, founded by Gluckman, has explicitly engaged in polemics with Evans-Pritchard’s analysis of the political system of the Nuer. Gluckman is of the opinion that we have only learned to understand the dynamics of the reconciliatory process from Elizabeth Colson’s study on ‘Social control of revenge in the society of the Zambian Plateau Tonga’. According to Gluckman and Colson the key to and understanding of feud and its reconciliation would lie in conflicting loyalty on the part of third parties, who would have equally strong ties with both warring parties especially through affinal relationships. As a result of clan exogamy (the obligation and the practice of marrying outside one’s own clan) the entire local community, both among the Nuer and among the Zambian Tonga, is a network, throughout, of affinal relationships. An outburst of conflict, especially in the case of manslaughter, brings a number of individuals to a point where their affines and their consanguineal relatives seeks to mobilise them simultaneously to two amps at the same time. Clearly it is in their advantage to solve their personal role conflict by seeking to terminate the conflict as a whole; they can do so by setting in motion the institution mechanism towards reconciliation (through compensatory payments), and by exerting their influence on both parties, persuading them to cease hostilities.

An important step in the understanding of reconciliation in the context of segmentary societies in South Sudan was et more recently by Simon Simonse in his book Kings of disaster, which I had the privilege to assess as external examiner at the Free University, Amsterdam, a few weeks before my professorial appointment there in 1990. For Simonse mediators of the type of the Nuer leopard skin headman are not merely catalysts, whose contribution t the social process is only indirect and inactive. With the support of a wealth of case material derived from Nilotic societies than the Nuer, he shows how the dynamics of the relationship between ‘mediator’ and ‘followers’ can take all sorts of forms. In many contexts the mediator himself become as key figure, charged with the task of giving symbolic form to the social in his capacity of rain maker; but on the other hand, if he fails in that task, he will become the literal victim, the literal scape goat, of that same society, which is tied to him by a love-hate relationship. The schemes proposed by Frazer and Girard would thus appear to have, albeit in greatly revised and updated form, an applicability which makes us see beyond the mere neutral role of reconciliation processes, and which make us realise also the less sociable and ethical side of the conciliatory role of earth priest, marabout, saint, herald, bard, as well as (in the more centralised political system) the king, in the African context.

RECONCILIATION AND THE LAW

In more centralised African political systems the social order is not only the product of an insecure balance between opposition and integration, nor only of the conflicting loyalty of kinsmen in the course of an informal social process, but also the result of that eminently African institution, litigation, which often is under the direct patronage of the chief or king.

In purely local litigation, at the village level, it may happen that for the sake of the shared interests of male kinsmen and affines, more profound personal and group conflicts are being dissimulated, and that the socially weaker party in the conflict (women, children, ex-slaves, and in general people of low social status) are forced to yield to these interests. In African village society this constitutes a situation of incomplete reconciliation, which calls for a continuation of the conflict with other, extra judicial means (sorcery, poisoning, slander, suicide). This kind of local litigation does not stand on its own, it is embedded in the total societal process of the local community; this may lead to a situation where, just like in Gluckman’s and Colson’s reinterpretation of Evans-Pritchard, conflicting loyalties also litigation work towards reconciliation, in the context of a small-scale society whose members are tied to each other by multiplex relationships. In other words, an independent court of law is not a probably phenomenon in such a context.

However, if the judges have a grater distance to the local community, if they are linked to a royal court or to a central modern state to which the local village society is subjected, and if the judges identify more with the political order and the legal ideas and ideals of the court and the state than with the ongoing social and political process at the village level, then the insistence on reconciliation at all costs may be rather more limited.

In itself the termination of conflict through adjudication may imply reconciliation. A context for such reconciliation is already provided by the fact that the pasties have agreed to put their case before the court (the shared pint of departure hence reconciliation may be achieved), and that a verdict is being pronounced which (under threat of being convicted for contempt of court, which is normally heavily sanctioned) normally implies that the conflict must henceforth be considered to be terminated. In such a case the underlying, shared judicial system furnishes implicitly the framework within which reconciliation may be achieved. Such a formal reconciliation, which amounts to nothing but the decision not to continue the conflict now that is has been formally adjudicated, may however often be too formal and too distant to convince as a form of genuine reconciliation. In the context of South Central Africa it is a common phenomenon to see that after such a formal legal verdict, after which the conflict is no longer actionable in court, the conflict is yet carried on, notably with extra-judicial means. If this happens, it must be clear that the judicial termination of conflict did not produce reconciliation in the meaningful sense of the word. This forces us to look further for such a definition of the concept of reconciliation that we might be able to express why in these cases we are not dealing with reconciliation proper, contrary to some other cases which also involve the intercession of the courts. Of course, when we seek to answer this question, we have to take into account what we said in the introduction about the limitations of anthropology a an empirical science which, contrary to what is reported about God and the ancestors, cannot look into our very hearts.

RECONCILIATION, RITUAL, AND THERAPY

In all this it is important to realise that African village societies -- not only those of pastoral semi-nomads like the Nuer, but also those of sedentary cultivators -- in general tend to be fairly unstable and little permanent social units.

For instance, among the Zambian Nkoya a village is nothing but a core of kinsmen which merely because of the members temporary and somewhat accidental co-residence happens to stand out among the wider kin group, which overlaps with other such groups anyway. Also because of their limited number of members, their low fertility, their high child mortality, and the prolonged stay of some of their members in urban areas, these localised kinship cores are involved in an incessant, often sinister competition over members. Someone’s position in Nkoya society is determined by the village which he or she dwells is at a particular moment in time -- but this is only a temporary choice for one of the several villages, and one of the several kin ores, to which a person may reckon oneself to belong. There are nearly always alternative choices, and often these are effected in the course o tie. The village is a spatial, but in the first place a kinship political given, one is ‘member’ of the village much more than ‘inhabitant. And very frequently one discontinues this membership, trading it for an alternative, by moving house to a different village. On the spur of personal conflicts, illness and death, fear of sorcery, and the ambition to gain a headman title for oneself, virtually any person in this society goes, in the first half one his or her life, through a kind of musical chairs, from village to village, in the course of which process ever different villages, kin cores, and senior kinsmen figure as protectors and sponsors. (The pattern is not very different for women and men, albeit that women may also chose nn-kinsmen as patrons by marrying them, while over the past hundred years or so they are no longer eligible to compete for royal and headmanship titles). In this process also the villages themselves, as concrete localised sets of dwellings, are far from stable: most village as physical conglomerates of dwellings in a specific place have only a life span of ten to twenty years.

In practice therefore Nkoya villages are temporary conglomerates of relative strangers, who usually have not grown up together, and who are unlikely to die as co-resident neighbours of one another. In their mutual relationships they are constantly conscious of the optional aspect o their state of co-residence, and they constantly look around for opportunities to improve their personal security mainly through intra-rural moving; here security is defined both in terms of supernatural protection (against illness, death and misfortune) as mediated by the elders -- provided these are not exposed to be witches themselves -- , freedom for sorcery-generating, interminable conflict, and freedom from hunger and exposure because of ecological plenty.

In order to counteract the chaos which constantly threatens the close relationships between members of this-- fairly common -- type of African village societies, artifices are need which deny or dissimulate the opportunist nature of his villages as merely temporary meetings places of relative strangers, -- artifices which turn these villages into something of a much more permanent and inescapable nature, so that their members will be domesticated into consensus and unity. The answer to this lies in collective rituals, in which the localised kin core, augmented with members who temporarily stay in town, celebrate their unite and actually bring it about in the first place, through music, dance, sacrifice and prayer. Many African village societies boast an extremely rich repertoire of ritual, and the attending forms of music, dance and verbal expression. These range from the solitary prayer at the village shrine of the hunter setting forth in the evening or the early morning, via reconciliatory rituals in the restricted circle of closest kinsmen around the village shrine after a conflict, to massive life rises rituals marking a girl’s attainment of maturity, a person’s culmination of life in the form of funerary celebrations, and finally the crucial ritual of name inheritance a year or o after the demise of a senior kinsman or kinswoman.

Ritual creates the possibility of reconciliation even if, or precisely if, the law cannot be involved because subjecting to external adjudication is seen as a breach, from the public social space, into the intimacy of the secluded social space of solidarity and of face to face relationships, such as exist in the family, the village, the small group of solidary neighbour in an urban ward, a circle of friends or co-religionists. In the African context therapy and ritual an scarcely be told apart: to every ritual a therapeutic effect is attributed, and although there are pragmatic therapies whose religious component is merely implied and does not become overt, yet outside the sphere of cosmopolitan medicine there are few African therapeutic situations which do not have a predominantly religious component. Reconciliation, vis-a-vis the supernatural (with the ancestor; with a spirit -ancestral or otherwise -- which manifests its presents through possession; with the High God; with the Holy Spirit, Christ, God in African Independent Christian churches) i a central datum in African ritual and therapy. Usually it implies an idiom in whose context also, and particularly, the reconciliation between living participants in the ritual can be achieved. We note a triangular relationship: the supernatural conceptually if not in reality mediates between human A in conflict with human B, and this opens up possibilities in the context of ritual, religious reconciliation, which differentiate this type from judicial and socio-political reconciliation: the indirect mediation between two humans via the supernatural third party, makes it possible that virtually the entire reconciliation process is overtly clad in purely religious and symbolic terms, so that the precise contradictions and conflicts causing the conflict in the first place, here for once may remain unarticulated, implied, even dissimulated. In stead of the active bricolage, the inspired selection of cultural material and of specific features of the situation at hand they concoct a reconciliatory message of sudden insight, in these ritual setting the standard available cosmology derived from the religious world-vie tends t be the source of common redressive understanding; the dramatic re-recognition of each others shared humanity may remain at the ritualised, pious, even bigoted level. Whether these features render ritual reconciliation the most effective and lasting form of reconciliation in the long run, is a different question.

Ritual rather produces the possibility, under certain conditions including the strict demarcation of a no-longer-general space and time, of preceding to reconciliation as a temporal but repetitive phase in a context which is otherwise marked by conflict and violence, e.g. annual fair, saints’ festivals, pilgrimages in the world of Islam and Christianity a well as elsewhere -- a we have already discussed above.

It is precisely the symbolic technology of ritual which offers the conceptual pssibility of yet resolving unsolvable contradictions, conjuring them, and opening up a repertoire of cultural elements which are available for bricolage and which allow the skilful mediator to bring out, often by sleight of hand, such unexpected communality and shared humanity (ubuntu, once again) which may strike the conflicting parties as revelatory, and exhort them to terminate their differences. This symbolic technology achieves this by forcing a breach into the spatio-temporal rationality in which rules and facts are supposed to be sacrosanct, immutable, and therefore conflicting positions, once logically based, cannot be shifted. Such technology yet allows, against all odds, the termination the reconciliation of conflicts which through their solid anchorage in accepted, though contradictory, social values of the participants involved, should be considered to be without such an outcome. The plasticity of symbolic elements in the sphere of the supernatural (after all, who an claim to have sensory perception of their true being?) leads on to the appeal to a superhuman agent. This enables a reconciliation precisely when one realises only too clearly that such reconciliation would have been ruled out on purely human ground, at the strictly concrete and rational level of the people involved. In many parts of Africa, ritual, especially under the experienced guidance of a diviner-priest in whatever traditional or present-day disguises (I have adopted one today, if your understand my argument fully) offers the possibility of externalising and sublimating the conflict between humans, transforming it into a conflict between humans and the supernatural -- and the latter kind of conflict we know how to handle, through sacrifices and other rites -- still reconciliation, though no longer directly between people, but over the top of their heads. Therapy and ritual are the means per excellence towards reconciliation in an extra-social, extra-human framework: reconciliation not with humans (who may be dead, unapproachable, inconsolable, hurt beyond repair -- the twentieth century has regrettably offered striking examples: the Holocaust, the apartheid state, the Rwanda genocide of 1994) but via symbols, in which the supernatural represents itself so that a judicial or politicised solution, which would no longer work, is rendered unnecessary. In this respect such reconciliation as is worked in the ritual-therapeutic context, is of a fundamentally different nature than that worked in the judicial and socio-political domain.

SORCERY AND SOCIAL CONFLICT AT A MACRO SCALE: TWO LIMITS TO THE AFRICAN SYMBOLIC TECHNOLOGY OF RECONCILIATION

Now, let us not lull ourselves to sleep, as if everything is African societies past and present, in the fields of law, therapy and ritual, was only geared to bringing about and maintaining beautiful, pure and perfect social relationships. This is a romantic, nostalgic image, bred both by the actual atrocities of aspects of the contemporary African experience, as well as by the realisation that also North Atlantic, increasingly global, society, despite its economic, political, military and symbolic hegemony, has totally failed to provide us with a meaningful and humanly profound future -- so why not cherish African alternatives? Of course, that is what we must do, but only on the basis of certain knowledge, not on the basis of mere wishful projections of our own, African or North Atlantic or global, personal predicaments. The best, and most convincing, form of Afrocentrism is the one based not on semi-intellectual myth, but on the methodologically underpinned, painstaking empirical reconstruction of Africa’s glorious past.

African societies did develop extraordinarily effective means, in the judicial, therapeutic and ritual domain, through which to prepare reconciliation and to bring it about. But on the other hand, these societies did need these very means, precisely because the social chaos, the distress and the annihilation which also in African societies, is constantly present as a threatening undercurrent. More so than in other societies? That is a question outside the scope of my present argument.

The sinister side of the short-lived euphoria of harmony in the village during or immediately after reconciliation, is the constant suspicion of possible sorcery, especially n the part of close kinsmen and neighbours. Without conflict no reconciliation, and the alternative to reconciliation is conflict which does not lead to reconciliation but which instead mobilises to the full extent man’s destructive capabilities and fantasies. Parallel to the group process (with its tendency to a cycle of reconciliation, conflict, fission) there is -- as we have indicated for the context of African kingship, a cosmology, a thought system defining the world of and around man, in such terms as:

In addition o the image -- so welcome in a superficially nostalgic view -- of Africa (of course, an African aggregated to an artificial, undifferentiated whole beyond recognition) as specialist domain for the technology of reconciliation at the micro level, there is the equally widely broadcast image of Africa as the homeland of witchcraft, of mankind’s sinister daydreams aimed at the desire for extravagant POWs, riches and knowledge, and of the cynical manipulation of humans and their so very vulnerable bodies in order to reach these goals. The African leader who on the outside is supposed to be the master of palaver and reconciliation, according to a complementary but equally vocal local social discourse may be the greatest witch around. The reconciliation which to outsiders makes the African village appear in all innocent peacefulness, is a reconciliation in conflicts over life and death.

Sorcery, at least in large parts of Africa, constitutes an instructive limiting concept for the study of reconciliation. Sorcery appears to be, in a nutshell, those forms of anti-social transgression which are not eligible for reconciliation; hence people’s resorting to private execution, violence, lynching, as alternatives to reconciliation -- and when such distressful and tragic means of conflict resolution are chosen, the actors legitimate their hose by reference to their adversary’s real or alleged acts of sorcery. Nonetheless, even in the sphere of sorcery all sorts of mechanisms are possible as conducive to reconciliation and reintegration: the ordeal, purification, submission to punishment, or neutralising of the accusation. Nonetheless, the fundamental thought behind African sorcery might be described, among other possible formulations, as the collective recognition of the fact that humans may be absolutely egoistic, absolutely anti-social. The witch (who incidentally may mainly exist is the form of his suspected victims’ anxieties and rumour) does not share in the social and symbolic world of humans, and therefore cannot truly e reconfirmed as participant in that world, through reconciliation. However, the African judicial, therapeutic and ritual practice is, most fortunately and instructively, not one of iron consistency: it acknowledges many procedures through which the person suspected of sorcery may seek to prove beyond reasonable doubt that he or she is not a witch, and hence that he or she, on second thoughts, does deserve -- albeit after reconciliation -- admission once more to the world of humans (ubuntu). Against the catharsis of reconciliation the catharsis of the witch and of diabolisation is juxtaposed, in the form of the confirmation of their inhumanity by the most inhuman mutilation and killing.

While thus the opposite to reconciliation -- e.g. sorcery -- is built into the very model of the African village society, there is as I said another limiting concept to the African technology of reconciliation: The fact that such reconciliation manifestly can seldom be seen to be effectively applied to the meso and macro level, i.e. at more comprehensive levels than the small-scale communities of village and urban wards. Apparently, in the study of reconciliation we must make a distinction according to levels of cope and relevance. The African technology of reconciliation at the micro level has so far not shown itself to be capable of containing the most destructive conflicts at he meso- and macro level, such as tend to occur in the modern, Postcolonial state. Ethnic violence, genocide, civil war, banditism, the total falling apart of the state in at least a dozen contemporary African national territories, are sufficient indications of the validity of this depressing statement. At the, more innocent, meso-level we might think of the continuing fission of African Christian churches, and in general of the relatively limited success and limited predictability of African formal organisation in the economic, bureaucratic, medical and educational domain.

Is this fairly negative record really due to the lack of potential and applicability of the African social technology of reconciliation? Or is it that, with the inroads of globalisation through colonialism, education, world religions, formal organisations, global media, and universal aspirations for personal commoditised consumption, we have not even tried to consider this potential, transforming African reconciliation on the basis of profound knowledge, and making it work in the modern setting which is to much more explosive, and on which so much more depend, than was foreseen when this technology of reconciliation was first formulated in a village context. If you have followed my argument, you will by now realise that African reconciliation in itself contains the potential at creative, selective reformulation for whatever context, whatever level, whatever conflict.

Over the past few years, South African managers, constitutional lawyers, and other intellectuals have dabbled in a largely nostalgic rekindling of the concept of ubuntu as a means to massage current transformation processes away from open conflict and open confrontation, no matter the inequalities and injustices which may be involved. In a society which has more to forget than it can possibly, humanly forgive, which has just gone through the exercise of the Truth and Reconciliation Committee process on the basis of a Christian model of confession and forgiveness for which I do not see many roots in the African technology of reconciliation as I have tried to understand, apply and describe it, and which is again preparing for the Herculean task of the imminent elections, for fundamental, and more beneficial lessons might be learned from the African tradition.

REFERENCES

Bartels, E.A.C., 1987, ‘Een dorpsheilige als bindmiddel: Over een vrouw als middelares in een conflict’, in: B. Venema, ed., Islam en macht, Assen: Van Gorcum.

Bernasconi, R., 1986, ‘Hegel and Levinas: The possibility of reconciliation and forgiveness’, Archivio di Filosofia, 54: 325-46.

Calmettes, J.-L., 1972, ‘The Lumpa Church and witchcraft eradication’, bijdrage, Conference on the History of Central African Religious Systems, University of Zambia/ University of California Los Angeles, Lusaka.

Colson, E., 1960, ‘Social control of vengeance in Plateau Tonga society’, in: Colson, E., The Plateau Tonga, Manchester: Manchester University Press, pp. 102-121.

Coser, L.A., 1956, The functions of social conflict, Londen: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Devisch, R., 1989, ‘Spiegel en bemiddelaar: De therapeut bij de Yaka van Zaïre’, in: Vertommen, H., Cluckers, G., & Lietaer, G., red., De relatie in therapie, Leuven: Universitaire Pers Leuven, pp. 331-357.

Ericksen, K.P., 1992, ‘ ‘‘Blood feuds’’: Cross-cultural variations in kin group vengeance’, Behaviour Science Research, 26, 1-4: 57-86.

Evans-Pritchards, E.E., 1967, The Nuer: A description of the modes of livelihood and political institutions of a Nilotic people, Oxford: Clarendon; first published 1940.

Fauth, W., ‘Hermes’, in: Ziegler, K. and Sontheimer, W., 1979, Der Kleine Pauly: Lexikon der Antike: Auf der Grundlage von Pauly’s Realencyclopädie der Classischen Altertumswissenschaft, München: Deutscher Taschenbuch, deel II, columns 1069-1076.

Gellner, E., 1969, Saints of the Atlas, Londen: Weidenfeld & Nicholson.

Geschiere, P.L., m.m.v. C.F. Fisiy, 1995, Sorcellerie et politique en Afrique: La viande des autres, Paris: Karthala, series Les Afriques.

Gluckman, H.M., 1955, ‘The peace in the feud’, in: Gluckman, H.M., Custom and conflict in Africa, Oxford: Blackwell, ch. 1, pp. 1-26.

Gluckman, H.M., 1963, Order and rebellion in tribal Africa, Londen: Cohen & West.

Kristensen, W.B., 1966, ‘De goddelijke heraut en het woord van God’, in: Kristensen, W.B., Godsdiensten in de oude wereld, Utrecht/ Antwerpen: Spectrum, 2nd ed., pp. 127-148.

Lame, D. de, 1996, Une colline entre mille: Le calme avant la tempête: Transformations et blocages du Rwanda rural, Ph.D., Vrije Universiteit, Amsterdam; Tervuren: Koninklijk Museum voor Midden-Afrika.

Marwick, M.G., 1965, Sorcery in its social setting, Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Meggitt, M., 1977, Blood is their argument: Warfare among the Mae Enga tribesmen of Papua New Guinea, Palo Alto: Mayfield.

Middleton, J. & D. Tait, 1958, ed., Tribes without Rulers: in African segmentary systems, Londen: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Oosterling, H., 1987, ‘Verzoening versus paradox: Habermas geconfronteerd met het geweld bij Bataille’, in: van de Burg, I., & Meyers, D., red., 1987, Bataille: Kunst, geweld en erotiek als grenservaring, Amsterdam: SUA, pp. 130-161.

Robertson Smith, W., 1927, Lectures on the religion of the Semites, I., The fundamental institutions, 3e ed., Cooke, Londen: Black.

Sigrist, C., 1967, Regulierte Anarchie, Olten/ Freiburg.

Simonse, S., 1992, Kings of disaster: Dualism, centralism and the scapegoat king in southeastern Sudan, Leiden etc.: Brill.

Turner, V.W., 1968, The drums of affliction: A study of religious processes among the Ndembu of Zambia, London: Oxford University Press.

van Binsbergen, W.M.J., & J.M. Schoffeleers, 1985, ‘Theoretical explorations in African religion: Introduction’, in: Binsbergen, W.M.J. van, & J.M. Schoffeleers, ed., Theoretical explorations in African religion, Londen/ Boston: Kegan Paul International, pp. 1-49.

van Binsbergen, W.M.J., 1977, ‘Law in the context of Nkoya society’, in: S. Roberts, ed., Law and the family in Africa, Den Haag/Parijs: Mouton, pp. 39-68.

van Binsbergen, W.M.J., 1991, ‘De chaos getemd? Samenwonen en zingeving in modern Afrika’, in: H.J.M. Claessen, ed., De chaos getemd?, Leiden: Faculteit der Sociale Wetenschappen, Rijksuniversiteit Leiden, 1991, pp. 31-47.

van Binsbergen, W.M.J., 1994, ‘Divinatie met vier tabletten: Medische technologie in Zuidelijk Afrika’, in: Sjaak van der Geest, Paul ten Have, Gerhard Nijhoff & Piet Verbeek-Heida, eds., De macht der dingen: Medische technologie in cultureel perspectief, Amsterdam: Spinhuis, pp. 61-110.

van Binsbergen, W.M.J., 1996, ed., Anthropology on violence: A one-day conference, Amsterdam: Vrije Universiteit, vakgroep Culturele Antropologie/Sociologie der Niet-Westerse Samenlevingen.

van Binsbergen, W.M.J., 1997, Virtuality as a key concept in the study of globalisation: Aspects of the symbolic transformation of contemporary Africa, The Hague: WOTRO, Working papers on Globalisation and the construction of communal identity, 3; revised complete Internet version,http://www.multiweb.nl/~vabin, link from homepage.

von Amira, K., 1909, ‘Der Stab in der germanischen Rechtssymbolik’, Abhandlungen königliche bayerische Akademie der Wissenschaften.

Werbner, R.P., 1972, ‘Sin, blame and ritual mediation’, in: Gluckman, H.M., red., 1972, The allocation of responsibility, Manchester: Manchester University Press, pp. 227-255.

Werbner, R.P., 1991, Tears of the dead, Londen: International Library/ Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press.

NOTES

1. I am indebted to the Trust Fund of the Erasmus University, Rotterdam, for funding the trip to South Africa In the context of which this paper was presented at the Human Sci ences Research Council, 21st April, 1999, and to the Human Sciences Research Council for this opportunity of sharing my current research. A more extensive, Dutch version was presented on the symposium 'Verzoend of verscheurd?', Centre for Contemplation, Free University, Amsterdam, 9 October, 1997. An earlier, Dutch version of this paper appeared in: In de marge, December, 1997.

2. Few Africanist anthropologists today would still speak of 'tribe' in this connection, but that is immaterial for our present argument.

| page last modified: 13-02-01 08:53:23 |  |

|||

|