AFRICAN SPIRITUALITY

an approach from intercultural philosophy

Wim van Binsbergen

|

AFRICAN SPIRITUALITY an approach from intercultural philosophy Wim van Binsbergen |

|

click here for an unformatted downloadable TXT version

There is

currently a hype in the production of encyclopedias on Africa,

and in this context Valentin Mudimbe approached me a few years

ago whether I would be willing to write the entry on

‘African spirituality’ for an encyclopaedia

of Africa and the African diaspora which he was editing. Never

having used the word ‘spirituality’ in any of my own

writings on African religion so far, and bargaining for time, I

asked him what I was to understand by it: time-honoured

expressions of historical African religion such as prayers at the

village shrine; the wider conceptual context of such expression,

including African views of causality, sorcery, witchraft,

medicine, the order of the visible and invisible world, and such

concepts as the person, ancestors, gods, spirits, nature, agency,

guilt, responsibility, taboo, evil, not to forget the ordering of

time and space in terms of religious meaning; the expressions of

world religions in Africa, especially Islam and Christianity; the

accommodations between these various domains. Mudimbe’s

answer was: all of the above, and whatever else you wish to bring

to the topic. Though unduly flattered by his request, I never

came round to writing the entry: I could not overcome the fear of

exposing myself as ignorant of the essence of African religion.

Very recently, I brought together in one website[ii] a

considerable number of my papers on African religion as written

over the years, also in preparation for a book largely to consist

of the same material. This has made me reflect on the very topic

Mudimbe invited me in vain to write on.

The readily available material from the website contains only

some fifteen of the myriad writings on African spirituality which

are in existence, and in that respect there is no special reason

to take these specific writings as our point of departure. Yet I

will do so, for the following reason: as far as these writings

are concerned, I have first-hand knowledge of the specific

empirical and existential conditions under which the statements

they contain came into being, and of the personal evolution of

the author who made these statements. Implicitly this means that

I appeal to introspection as one of my sources of knowledge.

While a time-honoured tool in the history of philosophy (think

e.g. of Socrates’ daimôn and Descartes

‘cogito ergo sum’), we are only

too well aware of the dangers of introspection.[iii] The

public representation of self in what may be alleged to be pure

introspection inevitably contains elements of performativity,

selection, structuring, and is likely to be imbued with elements

of transference reflecting the introspecting author’s

subconscious conflicts and desires. Incidentally the same

criticism applies, in varying degrees which have hardly been

investigated, to all other philosophical and social scientific

statements. Be this as it may, I rely on introspection only

implicitly in the present argument: mainly I will acknowledge my

personal recollection of the specific social processes of my own

gaining knowledge, or ignorance, of African spirituality.

The present argument may ultimately, in more final form, serve

towards the introduction of my book in the making, and this is

another incentive to write it. The extensive references to my own

published work merely serve to cover as many as possible of the

articles to be included in the prospective book.

What I wish to do is pose a number of obvious and

straight-forward questions, and attempt to give very provisional

answers to them, in order to initiate our further discussion on

these points:

•

Is there a specifically African spirituality?

•

Can we know African spirituality?

•

What specific themes may be discerned in African spirituality?

•

To what extent is African spirituality a process of boundary

production and boundary crossing at the same time?

•

Within these boundaries, what is being produced: group

sociability, the individual self, or both?

•

How can we negotiate the tension between local practice and

global description of African spirituality?

It is almost

impossible to separate this question from the next one,

concerning the epistemology of African spirituality. However, we

have to start somewhere, and it may be best to start where the

controversies and the politics of intercultural knowledge

production are most in evidence. The existence of a massive body

of writing specifically on African religion, and the

institutionalisation of this field in terms of academic journals,

professorial chairs, scholarly institutions, at least one

world-wide scholarly association, has helped to make the

existence of specifically African spirituality (or religion, I

will not engage in terminological debate here) into at least a

globally recognised social fact. But to

recognise the nature of social facts as being socially produced

at the same time raises the question of irreality, virtuality,

performativity, existence by appearance only. If we argue that

ethnicity is socially produced, we argue at the same time for the

deconstruction of ethnic identity claims as inescapable,

historically determined, absolute, unequivocal.[iv]

Something similar has been argued for culture.[v] Is it

now the turn for African spirituality to undergo the same

treatment?

African spirituality features prominently in the increasingly

vocal expressions by intellectuals, political and ethnic leaders,

and opinion-makers who identify as African or who can claim

recent[vi] African

descent. Of late such discussions have concentrated around the

Afrocentrist movement[vii] for

which I personally have great sympathy.

Here a dilemma arises.

One could either stress[viii]

(1)

the fact that the concept of ‘Africa’ is a fairly

recent geopolitical construct and therefore is unlikely to

correspond to any ontological reality informing, and mediated

through, spiritual expressions some of which (like royal cults,

ancestral cults, cults of the land) can be demonstrated[ix] to have

existed for centuries if not millennia on the soil of the African

continent. By taking this view one may have long-term historical

reality on one’s side, but at the same time one gives the

impression of seeking to rob those who identify with

‘Africa’ from their most cherished possession, their

most central identity.

Or,

alternatively, one may

(2)

affirm that there is something uniquely African, not just in

sheer terms of geographical location or provenance but also in

substance, thus playing into the cards of the Afrocentrists and

similar consciousness-raising forms of intellectual mobilisation.

But then one must be prepared to run the risk of

oversimplification, seeing one ‘African spirituality’

where in fact there are myriad different African spiritual

expressions, some as far apart as:

(a)

the cult of royal ancestors in West Africa under the Akan

cultural orientation, and

(b)

the ecstatic veneration of the Holy Spirit in Pentecostal

Southern African churches;

or

(c)

the veneration of land spirits in the somewhat thin Islamic

trapping of local saints in North Africa, and

(d)

the ecstatic cults of affliction associated with misfortune, a

unique personal spiritual quest, and the circulation of persons

and commodities across vast distances of space, as in the South

Central and Southern African ngoma complex;

or

(e)

the meticulous cultivation of female domesticity and sexuality in

South Central African girl’s initiation cults, and

(f)

the annual cult of the descent of the Cassara demiurge, revenger

and cleanser of witchcraft, in westernmost West Africa.

These examples, all within the range of my own African religious

research in over three decades, may be multiplied ad

libidum.

If many colleagues clamour to subsume these varieties of

spiritual expression under a common label, as

‘African’, it is not so much because these expressions

are situated in the African continental land mass, or manifestly

pertain to a recognisable shared tradition, but largely because

all of them may be cited to represent forms of local identity and

symbolic production on the part of people whose image of dignity,

whose image of spiritual and intellectual capability and

autonomy, has been eroded in recent centuries of a North Atlantic

mercantile, colonial and post colonial hegemonic assault.

‘African’ in my opinion primarily invokes, not a common

origin not shared with ‘non-African’ or

‘non-Africans’, nor a common structure, form or

content, but the communality residing in the determination to

confront and overcome such hegemonic subordination.

It is especially important to realise that ‘African’,

when applied to elements of cultural production, usually denotes

items which are neither originally African, nor exclusively,

confined to the African continent. Elsewhere I have extensively

argued how many cultural traits which today are considered the

central characteristics and achievements of African cultures,

have demonstrably a non-African origin, and a global distribution

pattern which extends far beyond Africa.[x] This

is not in the least a disqualification of Africa, for exactly the

same argument, and even more so, may be made for so-called

European characteristics and achievements, including Christianity

and modern science. It is only a reminder that broad continental

categories are part of geopolitics, of ideology and identity

construction, and not of detached analytic thought. There is a

famous passage in Linton’s Study of man[xi] in which he describes the morning

ritual of the average modern inhabitant of the North Atlantic:

from the slippers he puts on his feet to the God to whom he

prays, the cultural items involved in that process have a

heterogeneous and global provenance, most hailing from outside

Europe.

The cultural and intellectual achievements commonly claimed as

exclusive to the European continent, are a concoction of

transcultural intercontinental borrowings such as one may only

expect in a small peninsula attached to the Asian land mass and

due north of the African land mass, thrice the size of Europe.

What makes things European to be European, and things African to

be African, for that matter, is the transformative

localisation after diffusion.[xii]

Transformative localisation gave rise to unmistakably, uniquely

and genially Greek myths, philosophy, mathematics, politics,

although virtually all the ingredients of these domains of Greek

achievement had been borrowed from Phoenicia, Anatolia,

Mesopotamia, Egypt, Thracia, and the Danube lands. And a similar

argument could be made for many splendid kingdoms and cultures of

Africa.[xiii]

If we accept that ‘African’ today is primarily a

political category reflecting the desire to assert self-identity

and dignity in the face of subjugation and humiliation under

North Atlantic hegemony, then ‘African spirituality’

can no longer be defined, naively, as a particular way in which

the inhabitants of the African continent go about their

time-honoured religion, today, and in presumed continuity, to a

greater or lesser extent, with the religious patterns such as

these existed before European colonial conquest. We know that

‘African’ is a meaningless category except in contrast

with the ‘non-African’ implied in the term, and

implicated in a particular political history of hegemony

vis-à-vis what is so-called ‘African’. As befits the

place of origin of mankind, the African continent has the

greatest variety of somatic, cultural and religious forms in the

world. We cannot define Africans by reference to that variety.

What makes Africans Africans is not that they tend to have

heavily pigmented skins and woolly curly hair covering their

heads (this does not apply to all people residing in the African

continent, and moreover it does apply to many people outside the

African continent, including many not of recent African descent,

such as the original inhabitants of Southern India, Melanesia,

New Guinea and Australia), but that they have shared in the

experience of recent intercontinental political, military and

economic history. In asking the question as to the nature of

African spirituality, we are no longer primarily interested in

the ways in which ‘Africans’, of all people, use the

concepts of spirit, and the actions of prayer, sacrifice, ritual,

to endow their world with meaning, order, and intent, as if

things African constitute their entire world. African

spirituality can only be a political category, which seeks to

define a local spirituality (better probably: a locality of the

spirit) in the face of the threats, lures and inroads of global

processes beyond the local.

‘African spirituality’ then is a scenario of

tension between local and outside, utilising spiritual means (the

production, social enactment, and ritual transformation, of

symbols by a group which constitutes itself in that very process)

in order to try and resolve that tension. In the last

analysis, African spirituality is not a fixed collection of such

spiritual means (‘spiritual technologies’) which might

be labelled specifically ‘African’ if that epithet is

to denote geographical provenance. The means are extremely

varied, as we have seen. And in many cases these means are

imported intercontinentally from outside Africa. These cases

probably include spirit possession,[xiv] and

certainly such world religions as Islam and Christianity, --

these three forms of African spirituality together already sum up

by far the major religious expressions on the African continent

today.

The latter does not mean that these three forms of African

spirituality are inherently un-African and alien to the longue

durée of African cultural history. Spirit possession

is increasingly agreed to constitute a transformation, in recent

millennia, of the religion of Palaeolithic hunters whose

religious expression has been world-wide mediated (often in

shamanistic forms iconographically marked by deer[xv] and circle-dot motives,[xvi] which passed through Mesopotamia

and the eastern Mediterranean basin in the second millennium BCE)

in the particular form it took in the Northern half of Eurasia by

the onset of the Neolithic. It is likely that this North and

Central Eurasian spiritual expression was considerably indebted

to the emergence of art, symbolic thought, and language by

somatically modern man in Africa from 200,000 BP (and especially

100,000 BP) onwards.[xvii] Yet it

is my impression that African cults of possession and mediumship

derive primarily from a common Old World stock emanating from

North and Central Eurasia, and not so much from the direct

intra-African descendent forms of the Later Palaeolithic. More

recently, both Islam and Christianity emerged in a

Semitic-speaking cultural environment which was not only

geographically close to Africa, but towards whose genesis African

influences have been highly important: Mesopotamian influences on

ancient Judaism have been stressed by scholarship from the late

nineteenth century,[xviii] but it

is only in recent decades that the great influence of ancient

Egypt on that seminal world religion is widely admitted and

studied in detail;[xix] by the

same token, it is increasingly clear that the cradle of the

Semitic languages is to be sought in Northeast Africa (where even

today the wider linguistic super-family of Afroasiatic has its

greatest typological variety), and that many of the basic

orientations of the Semitic civilisations of Western Asia may

have parallels if not origins in the African continent.

To try and define the conditions under which the process of the

creation of locality in the face of a confusing and

identity-destroying outside world takes place, is the main

challenge of cultural globalisation studies today.[xx] Also in some of my own writings,

typically including those not emphatically appearing under the

heading of African religious studies, this process has been

explored.[xxi] Invariably, the process hinges on

the creation of a sense of community which involves the

installation, both conceptually (in shared language) and

actionally (through control of the flow of people and

commodities) of boundaries defining ‘us’ (a

‘we’ into which the acting and reasoning ‘I’

inserts herself) as against ‘them’. Without such

boundaries, no spirituality, yet, as we shall see, the very

working of spirituality is to both affirm and transgress these

boundaries at the same time -- so that ultimately,

African spirituality is about both the affirmation of a South

identity based on a particular historical experience, and the

dissolution of that identity into an even wider, global world.

The above

positioning of African spirituality has deliberately deprived the

concept from most of its entrenchedly parochial and mystical

implications. If the creation of community through symbols is a

social process aiming at selective and situational inclusion and

exclusion through conceptual and actional means, and if the

process is not limited to a specific selection of cultural

materials supposed to constitute, intrinsically, ‘African

spirituality’, then the vast majority of people identifying

as ‘Africans’ would at most times be excluded from the

creation of community undertaken by other ‘Africans’ in

a specific context of space, time and organisation.

For instance, a number of spiritual complexes, including one

revolving on the veneration of dead kings, another on girl’s

initiation and the spirit of menstruation and maturation named

Kanga, another on commoner villagers’ ancestral spirits, yet

another on spirits of the wild as venerated in cults of

affliction and in the guilds of hunters and healers, together

make up the spiritual life world of the contemporary Nkoya ethnic

group.[xxii] This statement needs to be

qualified in view of the fact that many who today identify as

Nkoya, including the groups dominant ethnic brokers and elite,

have undergone considerable Christian influence and would

primarily identify as Christians of various denominations,

primarily the Evangelic Church of Zambia, Roman Catholicism, and

recent varieties of Pentecostalism. Moreover, in the eighteenth

and nineteenth centuries, Islamic Swahili long-distance traders

penetrated into the land of Nkoya and left some small cultural

traces there. All these complexes define insiders and

outsiders in their own right, to such an extent that most Nkoya

tpople today could be said to be outsiders to most of what in

some collective dream of Nkoya-ness would be summed up as the

basic constituent features of the Nkoya spiritual world!

All Nkoya men are in principle excluded from participation in and

knowledge of the world of female initiation; women and all male

non-initiate hunters are excluded from the hunters’

guild’s cults except from the most public performances of

its dances and songs, and so on. Over the pastdecade, my research

on identity, culture and globalisation in Zambia has concentrated

on the annual Kazanga festival,[xxiii] the

main rural outcome of a process of ethnicisation by elite

urban-based Nkoya in the 1980s. The main feature of this festival

is that elements from all these spiritual domains (with exception

of Christianity, which however contributes the festival’s

opening prayer and the canons of decency governing dancers’

clothing and bodily movements) are pressed into service in the

two-day’s repertoire of the festival. The effect is that

thus all people attending the festival, whose globally-derived

format (including a formal programme of events, the participation

of more than one royal chiefs seated together, the re-enactment

of girl’s initiation dances by young women who have already

been initiated, the use of loudspeakers, the opening prayer and

national anthem, the careful orchestration of dancing movements

by dancers who are uniformly dressed, and who receive payment for

their activities, etc. etc.) is entirely non-local, are forged

into a performative, vicarious insidership, by partaking of a

recycled form of spirituality devoid of its localising

exclusivity. Here boundaries are crossed and dissolved, and the

most amazing thing is that -- as I argued at greater length

elsewhere -- the Nkoya people involved do not seem to notice the

difference between the original spiritual dynamics, and its

transformation and routinisation in the Kazanga context. Or

rather, if they notice the difference they appreciate the modern,

virtualised form even more than the original village forms.

However, one might also argue that it is only by sleight-of-hand

that the illusion of a more extensive insidership is created here

whereas in fact the essence of the virtualisation involved is

that all people involved, also the original insiders, are turned

into outsiders, banned from the domain where the original

spiritual scenario could be seen to be effective.

When such transformations of inside participation and outside

contemplation and exclusion exist, already within one cultural an

linguistic community with a small window on the wider, ultimately

global world, we should be very careful with claims as to the

sharing or not sharing of the spirituality involved. Central

to my argument is that African spirituality consists in a

political scenario, and that in that context the minutiae of

contents of a specific cultural repertoire, and a specific

biologically or socially underpinned birth-right, are largely or

even totally irrelevant.

This may be a difficult position to accept for cultural

essentialists including many Afrocentrists. Yet it is a position

which I have extensively elaborated and which subsumes my entire

intellectual career.[xxiv] It is

the position in which I claim to be a Dutchman, a professor of

intercultural philosophy, a Southern African sangoma, and an

adoptive member of a Nkoya royal family, all at the same time.

In the light of the constructed nature of any domain surrounded

by the boundaries that spirituality both creates and

transgresses, any spiritual domain, African or otherwise, is by

definition porous and penetrable -- in fact, it invites

being entered, but at a cost defined by the

spiritual boundaries surrounding it.

That cost is both interactional and conceptual. An exploration of

this cost amounts to defining the place and structure of

anthropological field-work as a technique of intercultural

knowledge production; it is here that the introspection mentioned

in my introduction comes in. Without engaging with the insiders

along the locally defined lines of etiquette, implied meanings,

shared local secrets, it is impossible to attain and to claim

insidership. Without engaging with the linguistic and conceptual

bases of such communality as the insiders create by means of

their spirituality, it is impossible to achieve insidership in

their midst. Such insidership is a social process also in this

sense that it cannot just be claimed by the person aspiring it;

quite to the contrary, it has to be extended, recognised and

affirmed by those who are already insiders, and who as such are

the rightful owners of the spiritual domain in question. These

are complex processes indeed. Not only the original outsider such

as the anthropologist seeking to enter from a background which

was initially far removed from that of the earlier insiders, but

also these insiders themselves in their process of affirming

themselves as insiders, have to struggle with massive problems of

acquisition of cognitive knowledge, language skills, details of

organisational, mythical, theological and ritual nature. Their

credentials as insiders are socially and perceptively mediated,

and as such contain a considerable element of performativity,

which in principle stands in tension vis-à-vis actual spiritual

knowledge and attitudes, for in the public production and

perception of the latter a non-per formative existential

authenticity tends to be taken for granted. Also the initial

outsider seeking to become insider must perform in order to

affirm her eligibility as insider, and this adds a layer of

potential insincerity to all claims of intimate spiritual

knowledge of secluded local domains.

Yet, despite all these qualifications, I can only affirm that,

yes, the very many distinct domains of locality created by

African spiritualities are as knowable to the initial outsider as

they are to the earlier insiders. The difference is one of degree

and not of kind. Paramount is the political scenario of

insertion, not the immutable facts of an allegedly fixed cultural

repertoire or birth-right; least of all a congenital

predisposition to acquire and appreciate a specific, reified

cultural repertoire — as racists, including racist variants

of Afrocentrism, would affirm.

Meanwhile knowing is not the same as revealing, and an entirely

new problematic arises when one considers the problem of how much

or how little the outsider having become insider in a specific

domain of African spirituality, is capable of revealing the

knowledge she has gained, to the outside world, globally, and in

principle in a globally understood international language. Here

at least three problems loom large:

•

Can everything, especially everything spiritual, be expressed in

language? The answer is inevitably: no, of course not.[xxv]

•

Can everything, especially everything spiritual, be transferred

from the specific domain of one language to that of another

language? Here the answer is: yes, to a considerable extent, but

not totally, cf. Quine’s principle of the indeterminacy of

translation).[xxvi]

•

Can one mediate inside knowledge to outsiders without betraying

the trust of fellow-insiders? Here the answer is: that depends on

the extent to which one allows the process of reporting to be

governed by the agency of these fellow-insiders -- if that extent

is minimal one’s reporting is downright betrayal and

intellectual raiding in the worst tradition of hegemonic

anthropology; but it is not impossible to mobilise the earlier

insiders’ agency, for many insiders today welcome global

mediation of their identity, and therefore may help to define the

forms in which they wish to see their own spiritual insidership

mediated.[xxvii]

I have

claimed that in principle African spirituality is a political

scenario devoid of specific cultural contents. In actual fact

however the range of variation in the cultural material that has

gone into the myriad specific constructions of African

spirituality, although wide, is not entirely unlimited.

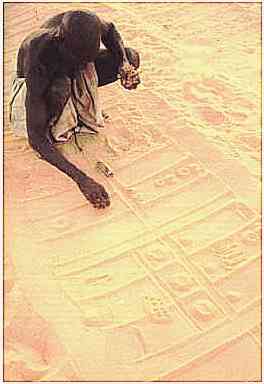

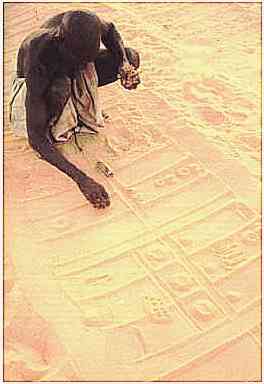

Let me give an example. In 1981, when guided by a hospitable new

roadside acquaintance into a West African village in Guinea

Bissau for the first time in my life, I could blindly point out

the village shrine and improvise meaningfully on its social and

spiritual significance, merely on the basis of having extensively

participated in village shrine ritual in South Central Africa, at

a distance of 5,000 km across the continent, and having written

comparative accounts of shrines in South Central and Northern

Africa.[xxviii] The same applies to spirit

possession, to whose South Central African forms I could relate

on the basis of my earlier research into similar phenomena in

North Africa.[xxix] The forms of kinship ritual and

royal ritual in West and Southern Africa are amazingly

reminiscent of each other, and I am gradually beginning to

understand the historical reasons for this, especially the

diffusion (taken for granted in the first half of the twentieth

century, and ridiculed in the second half) of royal themes from

Ancient Egypt.[xxx] The same similarity exists in the

field of divination methods, albeit that here the underlying

common source is not Ancient Egypt but late first-millennium CE

Middle-Eastern Islam having undergone the distant influence of

Chinese I Ching which goes back to the

second millennium BCE.[xxxi] But as

the latter forms of oracular ritual already indicate, there is no

compelling reason to limit our comparisons to the African

continent, and in fact there are continuities and similarities

extending all across Africa extending all over the Old World and

occasionally even into the New World.[xxxii] It

would be easy to spell out these themes and communalities more

fully, but for our present intercultural-philosophical argument

they are not essential; what is more, they would only detract us.

Adopting a

formal perspective that takes the greatest possible (or should I

say: an impossibly great) distance from cultural specificities, I

have suggested that African spirituality is a political scenario

of community generation through spiritual means. In other words,

African spirituality is a machine to generate boundaries.[xxxiii] However, a boundary which is

entirely sealed is no longer negotiable and amounts to the end of

the world. The very nature of a boundary in the human domain is

that it is negotiable, albeit only under certain conditions, and

at a certain cost. I have attempted to spell out some of these

conditions and costs.

The argument, if found not to be totally devoid of sense, has

implications for intercultural philosophy beyond the mere

analytical study of African spirituality. For also intercultural

philosophy itself could be very well defined in the very same

terms I have now employed for African spirituality. While forging

a specialist inside language amongst ourselves as intercultural

philosophers, we intend the boundary which

we thus erect around ourselves to be porous,

and to be capable of being transgressed by those we seek to

understand, and by whom we seek to be understood. Both within,

and across, that boundaries there will be limitations to the

extent to which we can know, understand, represent and mediate;

but the possibilities are well above zero.

There is an unmistakable kinship between my approach to African

spirituality as a content-unspecific boundary strategy towards

community, and Derrida’s approach to différance

as a strategy to both affirm and postpone the affirmation of

difference; little wonder that the above argument was written

shortly after I attempted to critically reflect on Derrida’s

1996 argument on religion.[xxxiv]

Besides my reluctance to spell out, at this point, whatever would

appear to be the specific contents of African spirituality after

all, another set of questions continue to bother me, leaving me

rather dissatisfied with the above argument while upholding its

general thrust, which would ultimately point to a definition of

religion beyond ontology, beyond metaphysics, as mainly a

(necessarily contentless) vector of sociability.

The following

dilemma arises at this point. Such boundary creation and boundary

crossing as goes on in the context of African spirituality, does

not only create situational and contextual communities to which

one may or may not be co-opted -- it also articulates an I who by

having the experiences engendered by these various spiritual

technologies, involves herself or himself in these domains of

community, and in the very process constitutes itself. Therefore

my emphasis, in the above argument, on the implied political

dimension of African spirituality, is demonstrably one-sided. It

is not the ad hoc community created within

spirituality-based boundaries, but the I who is the locus of

these experiences, because it is only the individual who

possesses the corporeality indispensable as the seat of

experience at the interface between self and outside world. As

Henk Oosterling aptly pointed out,[xxxv]

spirituality necessarily amounts to an embodied project. African

spirituality then is not only a social technology but also a

technology of individuality, of self. Is this reason

to distinguish between, let us say, social spirituality (the

technology of community) and religious spirituality (the

technology of self)? Is such a distinction at all possible? Or is

spirituality best understood as the nexus

between self and community, as the technology which (in the

classic Durkheimian sense)[xxxvi]

renders the social possible despite the centrifugal fragmentation

of the myriad individual conscious bodies out of which humanity

consists.

A second and

related point addresses my own positioning within the above

dilemma. I came to intercultural philosophy in the late 1990s out

of dissatisfaction with the objectifying stance of cultural

anthropology; before reaching that point, this dissatisfaction

had brought me to suspend professional anthropological distance:

I joined (1990-1991) the ranks of those whom I was supposed to

merely study, and became a Southern African diviner-priest (sangoma),

in ways described in several of my papers.[xxxvii] The

present argument goes a long way towards explaining how I can be

a sangoma, a North Atlantic professor of

philosophy, and a senior Africanist social researcher, at the

same time: if the essence of African spirituality (and any other

spirituality) is contentless, then the affirmation of belief is

secondary to the action of participation.[xxxviii] The

problem of actually believing in the central tenets of the sangoma

world-view (ancestral intervention, reincarnation, sorcery,

mediumship) then scarcely arises, and largely amounts to a sham

problem.

But not quite. For at the existential level one can only practice

sangomahood, and bestow its spiritual and

therapeutic benefits onto others as clients and adepts, if and

when these beliefs take on a considerable measure of validity,

not to say absolute validity, at least within the specific ritual

situation within which these practices are engaged in. The

community which this form of African spirituality (and other

forms of African and non-African spirituality) generates, clearly

extends beyond the level of sociability, and has distinct

implications for experience and cognition. It is a political

stance[xxxix] to insist on the validity of these sangoma

beliefs and to engage in the practices they stipulate, and thus

not to submit one-sidedly to the sociability pressures exerted by

another reference group (North Atlantic academic) and the belief

system (in terms of a secular, rational, scientific world-view)

they uphold; yet the latter belief system is worthy of the same

kind of respect and the same kind of politically motivated

sociability, as the sangoma one.

The dilemma is unmistakable, and amounts to an aporia. I solve it

in practice, day after day, by negotiating the dilemma

situationally and being, serially in subsequent situations I

engage in within the same day, both a sangoma and

a philosopher/ Africanist. But as yet I do not manage to argue

the satisfactory nature of this solution in discursive language.

And I suspect that this is largely because the kind of practical

negotiations that produce a sense of solution and that alleviate

the tension around which the dilemma revolves, defy the

consistency, boundedness and linearity of discursive conceptual

thought, -- in other words, the dilemma itself seems a rather

artificial by-product of rational theoretical verbalising on

intercultural and spiritual matters. As I argued elsewhere,[xl] discursive language is probably the

worst, instead of the most appropriate, vehicle for the

expression and negotiation of interculturality. And this renders

all academic writing on African spirituality of limited validity

and relevance. But why confine ourselves to writing and reading,

if the real thing is available at our very doorstep?

[i]

An earlier version of this paper was read at the June 2000

meeting of the Research Group on Spirituality, an initiative of

the Dutch-Flemish Association for Intercultural Philosophy NVVIF,

held at the Philosophical Faculty, Erasmus University Rotterdam.

I am indebted to the participants for their constructive remarks,

and particularly to Henk Oosterling, Cornée Jacobs, and Frank

Uyanne.

[ii]

http://come.to/african_religion .

[iii]

Dalmiya, V., 1993, ‘Introspection’, in: Dancy, J.,

& E. Sosa, eds., A companion to epistemology,

Oxford/ Cambridge (Mass.): Blackwell’s, first published

1992; Shoemaker, S., 1986, ‘Introspection and the

Self’, Midwest Studies in Philosophy,

9.

[iv]

van Binsbergen, W.M.J., 1992, Kazanga: Etniciteit in

Afrika tussen staat en traditie, inaugural lecture,

Amsterdam: Vrije Universiteit; shortened French version:

‘Kazanga: Ethnicité en Afrique entre Etat et

tradition’, in: Binsbergen, W.M.J. van, & Schilder, K.,

ed., Perspectives on ethnicity in Africa,

special issue, Afrika Focus, Gent,

1993, 1: 9-40; English version with postscript: van

Binsbergen, W.M.J., 1994, ‘The Kazanga festival: Ethnicity

as cultural mediation and transformation in central western

Zambia’, African Studies, 53, 2, 1994,

pp 92-125; van Binsbergen, W.M.J., 1999, ‘Culturen

bestaan niet’: Het onderzoek van interculturaliteit als een

openbreken van vanzelfsprekendheden, inaugural

lecture, chair of intercultural philosophy, Erasmus University

Rotterdam, Rotterdam: Rotterdamse Filosofische Studies; English

version in: van Binsbergen, Intercultural encounters,

o.c.; shortened English version also in http://come.to/vanbinsbergen .

[v]

van Binsbergen, Culturen bestaan niet, o.c.

Davidson even made a similar claim for languages, which is

relevant in this context since language is among the main

indicators of cultural and ethnic identity: Davidson, D., 1986,

‘A coherence theory of truth and knowledge’, in:

LePore, E., ed., Perspectives on the philosophy of

Donald Davidson, Oxford: Blackwell, pp. 307-19.

[vi]

‘Recent’ is here taken to mean: ‘having ancestors

who lived in the African continent during historical times, and

specifically during the second millennium of the common

era’. There is no doubt whatsoever that the entire human

species emerged in the African continent a few million years ago.

There is moreover increasing consensus among

palaeoanthropologists, based on massive and ever accumulating

evidence, that modern humans (Homo sapiens sapiens)

emerged in the African continent between 200,000 and 100,000

years ago, and from there brought language, symbolic thought,

representational art, the use of paint etc. to the other

continents. Cf. Roebroeks, W., 1995, ‘ ‘’Policing

the boundary’’? Continuity of discussions in 19th and

20th century palaeoanthropology’, in: Corbey, R. & B.

Theunissen, eds., Ape, man, apeman: Changing views

since 1600, Department of Prehistory, Leiden

University. Leiden, pp. 173-179, p. 175. Gamble, C., 1993, Timewalkers:

The prehistory of global colonisation, Bath: Allan

Sutton.

[vii]

On Afrocentrism, cf. the most influential and vocal statement:

Asante, M.K., 1990, Kemet, Afrocentricity, and

knowledge, Trenton, N.J.: Africa World Press; and the

(largely critical) secondary literature with extensive

bibliographies: Berlinerblau, J., 1999, Heresy in the

university: The Black Athena controversy and the responsibilities

of American intellectuals, New Brunswick etc.: Rutgers

University Press; Howe, Stephen, 1999, Afrocentrism:

Mythical pasts and imagined homes, London/New York:

Verso, first published 1998; Fauvelle-Aymar, F.-X., Chrétien,

J.-P., & Perrot, C.-H., 2000, eds., Afrocentrismes:

L’histoire des Africains entre Égypte et Amérique,

Paris: Karthala; and the discussion on Afrocentrism in Politique

africaine, November 2000 (in the press), to which I

contributed a critique of Howe, while I am also a contributor to

Fauvelle, Afrocentrismes, c.s., and the

author of a forthcoming review of Berlinerblau in the Journal

of African History.

[viii]

As I, for one, did in: van Binsbergen, W.M.J., 1997,

‘Rethinking Africa’s contribution to global cultural

history: Lessons from a comparative historical analysis of

mankala board-games and geomantic divination’, in: van

Binsbergen, W.M.J., 1997, ed., Black Athena: Ten Years

After, Hoofddorp: Dutch Archaeological and Historical

Society, special issue, Talanta: Proceedings of the

Dutch Archaeological and Historical Society, vols

28-29, 1996-97, pp. 221-254 -- currently being reprinted as Black

Athena Alive, Hamburg/Muenster: LIT Verlag, 2000.

[ix]

Cf. van Binsbergen, W.M.J., Religious change in Zambia:

Exploratory studies, London/Boston: Kegan Paul

International

[x]

van Binsbergen, W.M.J., ‘Islam as a constitutive factor in

so-called African traditional religion and culture: The evidence

from geomantic divination, mankala boardgames, ecstatic religion,

and musical instruments’, paper for the conference on

‘Transformation processes and Islam in Africa’, African

Studies Centre and Institute for the Study of Islam in the Modern

World, Leiden, 15 October, 1999, forthcoming in: Breedveld, A.,

van Santen, J., & van Binsbergen, W.M.J., eds., Dynamics

and Islam in Africa; van Binsbergen, ‘Rethinking

Africa’s contribution’, o.c.

[xi]

Linton, R., 1936, The study of man, New

York: Appleton-Century.

[xii]

On this key concept for contemporary ‘modified’ (to

adopt Martin Bernal’s term) diffusionist approaches, cf. van

Binsbergen, W.M.J., 1997, ‘Black Athena Ten Years After:

Towards a constructive re-assessment’, in: van Binsbergen, Black

Athena: Ten Years After, o.c.,

pp. 11-64, esp. p. 35f, and passim thoughout

this entire volume.

[xiii]

van Binsbergen, W.M.J., in preparation, Global Bee

Flight: Sub-Saharan Africa, Ancient Egypt, and the World —

Beyond the Black Athena thesis.

[xiv]

Eliade, M., 1968, Le chamanisme: Et les techniques

archaïques de l’extase, Paris: Payot; 1st ed

1951; Lommel, A., 1967, Shamanism, New York:

McGraw-Hill; Lewis-Williams, J.D., 1992, ‘Ethnographic

evidence relating to ‘‘trance’’ and

‘‘shamans’’ among northern and southern

Bushman’, South African Archaeological Bulletin,

47: 56-60; Halifax, J., 1980, Shamanic voices: The

shaman as seer, poet and healer, Harmondsworth:

Penguin Books; Bourgignon, E, 1968, World distribution and

patterns of possession states, in: Prince, R., ed., Trance and

possession states, Toronto: [publisher ] , pp. 3-34; Winkelman,

M., 1986, ‘Trance states: a theoretical model and

cross-cultural analysis’, Ethos, 14:

174-203; Goodman, F., 1990, Where the spirits ride the

wind: trance journeys and other ecstatic experience,

Bloomington, Indiana U.P, 1990; Ginzburg, C., 1992, Ecstasies:

Deciphering the witches’ sabbath, tr. R.

Rosenthal, Harmondsworth: Penguin Books; repr. of the first Engl.

edition, 1991, Pantheon Books, tr. of Storia notturna,

Torino: Einaudi, 1989; Campbell, J., 1990, The flight

of the wild gander, HarperPerennial; van Binsbergen,

‘Islam as a constitutive factor’, o.c.

[xv]

Rostovtsev, M.I., 1929, The animal style in south

Russia and China, Princeton: Princeton University

Press; Bunker, E.C., Chatwin, C.B., & Farkas, A.R., 1970,

‘Animal style’, in: Art from east to west,

New York; Cammann, Schuyler v. R., 1958, ‘The animal style

art of Eurasia’, Journal of Asian Studies,

17:323-39.

[xvi]

Segy, L., 1953, ‘Circle-dot sign on African ivory

carvings’, Zaïre, 7, 1: 35-54.

[xvii]

Anati, E., 1999, La religion des origines,

Paris: Bayard; French tr. of La religione delle origini,

n.p.: Edizione delle origini, 1995; Anati, E., 1986, ‘The

Rock Art of Tanzania and the East African Sequence’, BCSP

[ Bolletino des Centro Camuno di Studi Preistorici

] , 23: 15-68, fig. 5-51; Wendt, W.E., 1976, ‘

‘’Art mobilier’’ from Apollo 11 Cave, South

West Africa: Africa’s oldest dated works of art’, South

African Archaeological Bulletin, 31: 5-11; Gamble, Timewalkers,

o.c., with very complete bibliography.

[xviii]

E.g. Rogers, R.W., 1912, Cuneiform parallels to the Old

Testament, London etc.: Frowde, Oxford University

Press; Pinches, T.G., 1893, ‘Yâ and Yâwa in

Assyro-Babylonian inscriptions’, Proceedings of

the Society of Biblical Archaeology, 15: 13-15 (of

course totally obsolete now, but that is not the point). More

recent standard works on this topic include: Heidel, A., 1963, The

Gilgamesh epic and Old Testament parallels, Chicago:

University of Chicago Press, third edition, second edition 1949;

Pritchard, J.B., 1950, ed., Ancient Near Eastern texts

relating to the Old Testament, Princeton: Princeton

University Press (many times reprinted); Kitchen, K.A., 1966, Ancient

Orient and the Old Testament, London: Tyndale Press;

Craigie, P., 1983, Ugarit and the Old Testament,

Grand Rapids: Eerdmans

[xix]

Redford, D.B., 1992, Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in

ancient times, Princeton: Princeton University Press;

Williams, R.J., 1971, ‘Egypt and Israel’, in: Harris,

J.R., ed., The legacy of Egypt, 2nd ed.,

Oxford: Clarendon, pp. 257-290; Assmann, J., 1996, ‘The

Mosaic distinction: Israel, Egypt and the invention of

paganism’, Representations, 56; and

especially the comprehensive project undertaken by M. Görg,

editor of the series Fontes atque pontes, reihe

Ägypten und Altes Testament (Wiesbaden), e.g.: Görg,

M., 1977, Komparatistische Untersuchungen an

ägyptischer und israelitischer Literatur, Wiesbaden;

Görg, M., 1997, Israel und Ägypten,

Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft.

[xx]

Appadurai, A., 1995, ‘The production of locality’, in:

R. Fardon, ed., Counterworks: Managing the diversity of

knowledge, ASA decennial conference series ‘The

uses of knowledge: Global and local relations, London: Routledge,

pp. 204-225; Meyer, B., & Geschiere, P., 1998, eds., Globalization

and identity: Dialectics of flow and closure, Oxford:

Blackwell; Fardon, R., van Binsbergen, W.M.J., & van Dijk,

R., 1999, eds., Modernity on a shoestring: Dimensions

of globalization, consumption and development in Africa and

beyond, Leiden/London: EIDOS; de Jong, F.,

‘Modern secrets: The production of locality in Casamance,

Senegal’, Ph.D, University of Amsterdam, forthcoming (2001).

[xxi]

van Binsbergen, W.M.J., 1991, ‘De chaos getemd? Samenwonen

en zingeving in modern Afrika’, in: H.J.M. Claessen red., De

chaos getemd?, Leiden: Faculteit der Sociale

Wetenschappen, Rijksuniversiteit Leiden, 1991, pp. 31-47; van

Binsbergen, W.M.J., 1997, Virtuality as a key concept

in the study of globalisation: Aspects of the symbolic

transformation of contemporary Africa, The Hague:

WOTRO [ Netherlands Foundation for Tropical Research, a division

of the Netherlands Research Foundation NWO ] , Working papers on

Globalisation and the construction of communal identity, 3, also

available in: http://come.to/vanbinsbergen ; van Binsbergen, W.M.J., 1998, ‘Globalization

and virtuality: Analytical problems posed by the contemporary

transformation of African societies’, in: Meyer, B., &

Geschiere, P., eds., Globalization and identity:

Dialectics of flow and closure, Oxford: Blackwell, pp.

273-303; van Binsbergen, W.M.J., ‘Witchcraft in modern

Africa as virtualised boundary conditions of the kinship

order’, in press in: G. Bond, & Ciekawy, E., eds.,

Witchcraft dialogues: New epistemological and

anthropological approaches to African witchcraft, my

contribution available on: http://come.to/african_religion ; van Binsbergen, W.M.J., 2000, ‘Sensus

communis or sensus particularis? A social-science comment’,

in: Kimmerle, H., & Oosterling, H., 2000, eds., Sensus

communis in multi- and intercultural perspective: On the

possibility of common judgments in arts and politics,

Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann, pp. 113-128, also

available on http://come.to/vanbinsbergen ; van Binsbergen, W.M.J., 1994, ‘Dynamiek van

cultuur: Enige dilemma's van hedendaags Afrika in een context van

globalisering’, Antropologische Verkenningen,

13, 2, 17-33, English version: van Binsbergen, W.M.J., 1995,

‘Popular culture in Africa: dynamics of African cultural and

ethnic identity in a context of globalization’, in: van der

Klei, J.D.M., ed., Popular culture: Africa, Asia and

Europe: beyond historical legacy and political innocence,

Proceedings Summer-school 1994, Utrecht: CERES, pp. 7-40.

[xxii]

van Binsbergen, Religious change, o.c.;

van Binsbergen, W.M.J., 1992, Tears of Rain: Ethnicity

and history in central western Zambia, London/Boston:

Kegan Paul International; van Binsbergen, W.M.J., &

Geschiere, P.L., 1985, ‘Marxist theory and anthropological

practice: The application of French Marxist anthropology in

fieldwork’, in : van Binsbergen, W.M.J., & Geschiere,

P.L., ed., Old modes of production and capitalist

encroachment: Anthropological explorations in Africa,

Londen/ Boston: Kegan Paul International, pp. 235-289; a shorter

version specifically on religion included in: http://come.to/african_religion .

[xxiii]

van Binsbergen, Kazanga, Dutch, English and

French version, oo.c. van Binsbergen,

W.M.J., 1999, ‘Nkoya royal chiefs and the Kazanga Cultural

Association in western central Zambia today: Resilience, decline,

or folklorisation?’, in: E.A.B. van Rouveroy van Nieuwaal

& R. van Dijk, eds., African chieftaincy in a new

socio-political landscape, Hamburg/ Münster:

LIT-Verlag, pp. 97-133. French version in press. Further

discussions of the Kazanga festival in my Virtuality,

o.c., ‘Popular culture in Africa’, o.c.,

and ‘Sensus communis or sensus particularis?’, o.c.

[xxiv]

van Binsbergen, ‘Culturen bestaan niet’, o.c..

[xxv]

Quine, W.V.O., 1960, Word and object,

Cambridge: MIT Press.

[xxvi]

Hookway, C., 1993, ‘Indeterminacy of translation’, in:

Dancy, J., & Sosa, E., eds., A companion to

epistemology, Oxford/ Cambridge (Mass.):

Blackwell’s, first published 1992; Wright, C., 1999,

‘The indeterminacy of translation’, in: Hale, B., &

Wright, C., 1999, eds., A companion to the philosophy

of language, Oxford: Blackwell, first published 1997,

pp. 397-426; Quine, W.V.O., 1970, ‘On the reasons for the

indeterminacy of translation’, Journal of

Philosophy, 67: 178-183; Quine, Words, o.c.

[xxvii]

Cf. van Binsbergen, W.M.J., 1984, ‘Can anthropology become

the theory of peripheral class struggle? Reflexions on the work

of P.P.Rey’, in: van Binsbergen, W.M.J., & G.S.C.M.

Hesseling, G .S.C.M., eds, Aspecten van staat en

maatschappij in Afrika: Recent Dutch and Belgian Research on the

African state, Leiden: African Studies Centre, pp.

163-80; earlier German version in: van Binsbergen, W.M.J., 1984,

‘Kann die Ethnologie zur Theorie des Klassenkampfes in der

Peripherie werden?’, Österreichische Zeitschrift

für Soziologie, 9, 4: 138-48. An extensive attempt to

create intercultural intersubjectivity in the rendering of

ethnographic knowledge is described in: van Binsbergen, Tears,

o.c.

[xxviii]

van Binsbergen, W.M.J., 1976, ‘Shrines, cults and society in

North and Central Africa: A comparative analysis’, paper

read at the Association of Social Anthropologists of Great

Britain and the Commonwealth (ASA) Annual Conference on Regional

Cults and Oracles, Manchester, 35 pp; soon available at http://come.to/african_religion ; Van Binsbergen, W.M.J., 1979, ‘Explorations

in the sociology and history of territorial cults in

Zambia’, in: Schoffeleers, J.M., ed, 1979, Guardians

of the land, Gwelo: Mambo Press, pp. 47-88; revised

edition in: van Binsbergen, Religious change,

o.c., chapter 3, pp. 100-134,

[xxix]

van Binsbergen, Religious change, o.c.;

van Binsbergen, W.M.J., 1985, ‘The cult of saints in

North-Western Tunisia: an analysis of contemporary pilgrimage

structures’, in: E.A. Gellner, ed., Islamic

dilemmas: reformers, nationalists and industrialization: The

Southern shore of the Mediterranean, Berlin, New York,

Amsterdam: Mouton, pp. 199-239; Van Binsbergen, W.M.J., 1980

‘Popular and formal Islam, and supralocal relations: the

highlands of north-western Tunisia, 1800-1970’, Middle

Eastern Studies, 16: 71-91; van Binsbergen, W.M.J.,

forthcoming, Religion and social organisation in

north-western Tunisia, Volume I: Kinship, spatiality, and

segmentation, Volume II: Cults of the land, and Islam;

van Binsbergen, W.M.J., 1988, Een buik openen,

Haarlem: In de Knipscheer.

[xxx]

van Binsbergen, Global Bee Flight, o.c.,

with extensive discussion of the literature.

[xxxi]

van Binsbergen, ‘Rethinking’, o.c.;

van Binsbergen, W.M.J., 1994, ‘Divinatie met vier tabletten:

Medische technologie in Zuidelijk Afrika’, in: Sjaak van der

Geest, Paul ten Have, Gerhard Nijhoff en Piet Verbeek-Heida,

eds., De macht der dingen: Medische technologie in cultureel

perspectief, Amsterdam: Spinhuis, pp. 61-110; van Binsbergen,

W.M.J., 1996, ‘Time, space and history in African divination

and board-games’, in: Tiemersma, D., & Oosterling,

H.A.F., eds., Time and temporality in intercultural perspective:

Studies presented to Heinz Kimmerle, Amsterdam: Rodopi, pp.

105-125; van Binsbergen, W.M.J., 1995, ‘Four-tablet

divination as trans-regional medical technology in Southern

Africa’, Journal of Religion in Africa, 25, 2: 114-140; van

Binsbergen, W.M.J., 1996, ‘Transregional and historical

connections of four-tablet divination in Southern Africa’,

Journal of Religion in Africa, 26, 1: 2-29; van Binsbergen,

‘Islam as a constitutive factor’, o.c.;

van Binsbergen, W.M.J., 1996, ‘The astrological origin of

Islamic geomancy’, paper read at ‘The SSIPS [ Society

for the Study of Islamic Philosophy and Science ] / SAGP [

Society of Ancient Greek Philosophy ] 1996, 15th Annual

Conference: ‘‘Global and Multicultural Dimensions of

Ancient and Medieval Philosophy and Social Thought: Africana,

Christian, Greek, Islamic, Jewish, Indigenous and Asian

Traditions, Binghamton University’’, Department of

Philosophy/ Center for Medieval and Renaissance studies (CEMERS).

[xxxii]

The latter applies e.g. to cat’s cradles (games consisting

of the manual manipulation of a tied string), certain

board-games, and the form of the Southern African divination

tablets, which have amazingly close parallels among the North

American indigenous population; cf. Culin, S., 1975, Games

of the North American Indians, New York: Dover;

fascimile reprint of the original 1907 edition, which was the Accompanying

Paper of the Twenty-fourth Annual Report of the Bureau of

American Ethnology of the Smithsonian Institution, 1902-1903,

by W.H. Holmes, Chief.

[xxxiii]

Partly on the basis of earlier work by Jaspers and Bataille among

others, in the final quarter of the twentieth century the nature

and production of boundaries attracted a considerable amount of

research in philosophy and the social sciences. For philosophy,

cf., for instance, Burg, I. van de, & Meyers, D., ed., 1987, Bataille:

Kunst, geweld en erotiek als grenservaring, Amsterdam:

SUA; Cornell, D., 1992, The philosophy of the limit,

New York: Routledge; Le passage des frontières: Autour

du travail de Jacques Derrida, Paris: Galilée, 1993;

Kimmerle, H., 1983, ‘Dialektik der Grenze und Grenze der

Dialektik’, in: Dialektik heute: Rotterdammer

Arbeitspapiere, Bochum: Germinal, pp. 127-141;

Kimmerle, H., 1985, ‘Schein im Vor-Schein der Kunst:

Grenzüberschreitungen zur Identität und zur

Nicht-Identität’, Tijdschrift voor Filosofie,

47: 473-492; Procée, H., 1991, Over de grenzen van

culturen: Voorbij universalisme en relativisme,

Meppel: Boom; Oosterling, H., 1996, Door schijn

bewogen: Naar een hyperkritiek van de xenofobe rede,

Kampen: Kok Agora, pp. 138ff and passim. And

for the social sciences: Barth, F., 1969, ed., Ethnic

groups and boundaries: The social organization of culture

differences, Boston: Little, Brown & Co; Devisch,

R., 1981, ‘La mort et la dialectique des limites dans une

société d’Afrique centrale’, in: Olivetti, M., ed., Filosofia

e religione di fronte alle morte, Archivio di Filosofia,

1-3: 503-527; Devisch, R., 1986, ‘Marge, marginalisation et

liminalité: Le sorcier et le devin dans la culture Yaka au

Zaïre’, Anthropologie et Sociétés,

10, 2: 117-37; Anthias, E., & Yuval-Davis, N., 1992, Racialised

boundaries, London: Routledge; Turner, V.W., 1969, The

ritual process, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul;

Schlee, G., & Werner, K., 1996, Inklusion und

Exklusion: Die Dynamik von Grenzziehungen im Spannungsfeld von

Markt, Staat und Ethnizität, Koln: Rudiger Koppe

Verlag. In a follow-up to the Research Group on Spirituality, the

NVVIF proposes to investigate the nature of cultural boundaries

in the context of the multicultural society, taking as point of

departure the common observation that such boundaries are often

produced, in public and performative situations, to be

deliberately and emphatically non-pourous.

[xxxiv]

Presumably the argument would win from being combined with my

argument on Derrida’s 1996 approach to religion; this will

be attempted in a later version. Cf. van Binsbergen, W.M.J.,

‘Derrida on religion: glimpses of interculturality’,

paper read at the April 2000 meeting of the Research Group on

Spirituality, Dutch-Flemish Association for Intercultural

Philosophy, now available on the website of the NVVIF: http://come.to/interculturality .

[xxxv]

At the session where this paper was first presented.

[xxxvi]

Durkheim, E., 1912, Les formes élémentaires de la vie

religieuse, Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

Durkheim departs from what he considers the fundamental condition

for religion: the distinction between sacred and profane, which

may take all sorts of forms in concrete settings of time and

place, but whose fundamental and universal (!) feature is that it

is absolute. As such the distinction between

sacred and profane is not only the basis for all rational

thought, but particularly for a cosmological partitioning of the

world in terms of sacred and profane. Sacred aspects of the world

(given aspects of the natural world such as animal species

(religiously turned into totems), but also man-made aspects:

events, human acts, concepts, myths) are not sacred by some

aspect of their intrinsic nature, but there sacredness is

superimposed by collective human representations; the selection

of things sacred is entirely arbitrary and therefore can vary

from society to society and from historical period to historical

period — what is involved is merely the application, with

endless variation, of the distinction between sacred and profane.

The sacred is nothing in itself, but a mere symbol -- but of

what? The sacred is subject to a negative cult of avoidance,

taboo, but also to a positive cult of veneration. It is essential

that this cult is a collective thing, in which the group

constitutes itself as a congregation, a church -- Durkheim uses

this world (‘église’) in the original etymological

sense (ekklesia, i.e. ‘people’s

assembly’) and without Christian implications: his own

background was Jewish, and his argument is largely underpinned by

ethnographic reference to the religion of Australian Aborigines,

who at the time had undergone virtually no exposure to

Christianity. Durkheim then makes his genial step of identifying

the social, the group, as the referent which is ultimately

venerated in religion. Here Durkheim is also indebted to

Comte’s idea of a ‘religion de l’humanité’

as a requirement for the utopian age when a

‘positivist’, rational science will have eclipsed all

the religious and philosophical chimera of earlier phases in the

development of human society. It is the group which, through its

transformation into a religious symbol -- a transformation of

which the adherents themselves are largely or completely unaware

-- , inspires the believer and the practitioner of ritual with

such absolute respect that their ritual becomes an

‘effervescence’, a heated melting together into social

solidarity by which the group constitutes itself and perpetuates

itself, and in which the individual (prone to profanity,

anti-social egotism, sorcery) can transcend his own limitations,

can give up his individuality, and become part of the group, for

which the individual is even prepared to sacrifice not only

ritual prestations, but also himself. Without religion no

society, but it is society itself which is the central object of

religious veneration; and from this spring all human thought, all

logical and rational distinctions, concepts of space and time,

causation etc.

[xxxvii]

van Binsbergen, W.M.J., 1991, ‘Becoming a sangoma: Religious

anthropological field-work in Francistown, Botswana’, Journal

of Religion in Africa, 21, 4: 309-344; van Binsbergen,

W.M.J., 1998, ‘Sangoma in Nederland: Over integriteit in

interculturele bemiddeling’, in: Elias, M., & Reis, R.,

eds., Getuigen ondanks zichzelf: Voor Jan-Matthijs

Schoffeleers bij zijn zeventigste verjaardag,

Maastricht: Shaker, pp. 1-29; both papers available in English

versions on: http://come.to/vanbinsbergen , and in preparation in: van Binsbergen, W.M.J., Intercultural

encounters: Towards an empirical philosophy.

[xxxviii]

A point elaborated in: Van Binsbergen, W.M.J., 1981,

‘Theoretical and experiential dimensions in the study of the

ancestral cult among the Zambian Nkoya’, paper read at the

symposium on Plurality in Religion, International Union of

Anthropological and Ethnological Sciences Intercongress,

Amsterdam, 22-25 April, 1981, 22 pp; available in: http://www.geocities.com/africanreligion/ancest.htm .

[xxxix]

van Binsbergen, ‘Becoming’, o.c.;

‘Sangoma in Nederland’, o.c.

[xl]

van Binsbergen, W.M.J., 1999, ‘Enige filosofische aspecten

van culturele globalisering: Met bijzondere verwijzing naar Malls

interculturele hermeneutiek’, in: Baars, J., & Starmans,

E., eds, Het eigene en het andere: Filosofie en

globalisering: Acta van de 21 Nederlands-Vlaamse Filosofiedag,

Delft: Eburon, pp. 37-52; English version available on: http://come.to/vanbinsbergen , and in preparation in: van Binsbergen, W.M.J., Intercultural

encounters: Towards an empirical philosophy.

| page last modified: 13-02-01 12:23:03 |  |

|||

|