|

Supervision and fieldwork trip to Indonesia, 1-14 August 2007 |

return to current Topicalities page | return to Shikanda portal

Introduction |

||

| PHOTOGRAPHS all photographs © 2007 Wim van Binsbergen, unless stated otherwise

Professor Bambang Sugiharto in the private museum of his friend Sunaryo, on which he recently published a bilingual (Indonesian/ English) biographical and critical study |

In the first two weeks of August 2007, Wim van Binsbergen visited the Universitas Katolik Parahyangan (UNPAR, 'The Catholic University of Heaven' -- i.e. 'of the House of the Gods'), Bandung, West Java, Indonesia, as the guest of the postmodern philosopher and aestheticist Professor Bambang Sugiharto of the Department of Philosophy and the Centre for Cultural and Religious Studies (CCRS). | |

Mr Djunatan's PhD thesis project |

||

| The main purpose of the

trip was to complement by face-to-face interaction the

supervision by correspondence of the PhD student

Stephanus Djunatan, whose proposed PhD thesis (to be

defended before the Erasmus University Rotterdam) will be

an exploration of the Deleuzian principle of affirmation.

For this purpose a number of supervision sessions were conducted, some jointly with Prof. Sugiharto, with Mr Djunatan, on the basis of the latter's written material so far. A substantial section of the proposed

PhD thesis (to be defended before the Erasmus University

Rotterdam) will be an exploration of the Deleuzian

principle of affirmation. This will consist of

This Sunda lived epistemology and cosmology are to be identified by fieldwork, and as a philosopher Mr Djunatan has no earlier specific training in empirical intercultural knowledge production. Therefore some minimal component of initial fieldwork training had to be part of this supervision trip. |

||

Two seminars |

||

One unexpected parallel between the Sunda people of West Java and the Nkoya people of Western Zambia is that their ethnic articulation before their respective modern state takes, among other strategies, the form of the publication and distribution of annual calendars in their mother tongue, in which the celebration of local custom and local prominents is combined with an affirmation of the cherished local names ofthe months, and special divisions and festivals of their calendar. |

In order to establish an

intellectual and dialogical framework for such fieldwork,

two formal seminars were organised. In the first (Friday 3rd August 2007), before the UNPAR Department of Philosophy in collaboration with Quest: An African Journal of Philosophy / Revue Africaine de Philosophie, Wim van Binsbergen explored a topic in Intercultural Philosophy: The second seminar took place on Saturday 4th Agust 2007, and was given jointly by Mr Stephanus Djunatan and Wim van Binsbergen, before the Centre for Cultural and Religious Studies (CCRS), UNPAR. The general topic was Sunda culture and history. This had attracted a considerable number of specialist in the culture, religion and language (i.e. Sundanese) of West Java, including some of the leading figures of the increasingly vocal Sunda ethnic group, which under President Suharto's New Order (1966-1998) had been marginalised in favour of Central Java, but which is now in ascendance again under a new decentralising dispensation favoured by the Indonesian constitution (the Pancasila). Mr Djunatan set out his proposed fieldwork project in some detail. In the discussion he received very enthousiastic and generous response from the assembled specialists, most of whom were born members of the Sunda ethnic group (contrary to Mr Djunatan himself). Thus the seminar amounted to an excellent launching of this research project. Subsequently, Wim van Binsbergen presented current views (including those of Oppenheimer and Dick-Read) concerning the Sunda thesis of prehistoric intercontinental cultural flow from Indonesia: Exploiting the semantic possibilities of the word Sunda to the full (in the expression 'Sunda thesis'and 'Sunda Plat' it is meant as a general term for the entire archipelago of Indonesia, yet local people in West Java primarily understand it as a designation of their own region ethnic identity), the audience responded very positively to what they seem to have largely understood to be an academic celebration (by a representative of the former colonizing power of all people) of the primacy of the Sunda identity on a national and even global scale. As a specialist on African ethnicity, Wim van Binsbergen is used to such mobilising appropriations, yet the appeal of ethnic revival and recognition was brought home very forcefully in this context. An invitation to repeat the same presentation for a much larger Bandung audience could not be honoured due to our already very tight programme. |

|

Fieldwork in and above the desa of Rawabogo, Ciwidey, West Java |

||

At various shrines in the sanctuary, the rock face is grinded away into a smooth surface; each pilgrim does some more grinding and is exhorted to smear his face with the resulting white powder, as in a parallel with the white kaolin powder which in Africa is a major epiphany of the sacred

Many rocks in the sanctuary are strikingly indented, in a manner suggested not of natural erosion but of man-made cupmarks. Yet apart from the neatly square steps hewn out in the rock, there are no signs here of megalithic man-made stone constructions, as elsewhere in Indonesia

Especially inside the various shrines (marked by remnants of offerings), and like here at the very top of the maintain, the rock face is densely inscribed with recent graffiti -- some by mere holidaymakers, but most by pilgrims who came here with a pilgrim. The graffiti are a course of vexation to the guardian, but there is nothing they can do about it. Clearly the pilgrims see their action not as disrespectful. Note the many cupmarks.

The guardian and the adept Mr Dayat, who serves as an acolyte, making an offering at one of the shrines

The Throne of the King of Sunda

The office of the Forestry Service, near the entrance of the sanctuary The Adept Mr Dayat donates his headscarf to Wim van Binsbergen, to wear when lecturing on the Sunda culture (photo © 2007 Henri Ismail) Two generations of guardians in conversation with Mr Dayat (photo © 2007 Henri Ismail) Onwards to the top (photo © 2007 Henri Ismail) Our pilgrimage party, and the local motorcyclists who brought us halfway the top on their buddyseats (photo © 2007 Henri Ismail) Mr Dayat squeezes through the narrow rocks in an attempt at spiritual rebirth, supervised by the guardian (photo © 2007 Henri Ismail) Theguardian prays at one of the shrines (photo © 2007 Henri Ismail) |

An official sign at the entrance of the sanctuary combines touristic and spiritual references

fieldwork in full swing: Mr Stephanus Djunatan MA (left) and Mr Henri Ismail MA taking notes during the spiritual conversation which develops at tea time.

parat of the offerings, which have to be renewed every Tuesday and Friday, but more frequently when pilgrims visit the lodge

Like in Africa, no cultic healing practice without a government license

The guardian making an offering in the cave where (in defiance of al the lofty, personal spirituality of self-realisation and pure intention so stressed in the guardian's discourse) against a token money gift wealth may be secured; note the black shopping bag containing the guardian's offerings, matches etc., including a hundle of scarlet incense sticks; also note the graffiti

Official sign prohibiting littering and collecting of firewood and other vegetal matter -- in vain At the very top, a narrow platform awaits for the final spiritual elevation (photo © 2007 Henri Ismail) Mr Dayat reclines against the head-shaped indebture in the rock, while the guardian oversees his prayer (photo © 2007 Henri Ismail) Another pilgrimage party under a different leader, at the sanctuary's First Gate. Note the excessive veiling of the female toddler, centre top (photo © 2007 Henri Ismail) The mosque at the very entry gate of the sanctuary, proclaiming it a contested space. Yet Islamic prayer formulae abound in the guardians rites (photo © 2007 Henri Ismail) The guardian directs the spiritual concentration of Mr Dayat (photo © 2007 Henri Ismail) Littering of the path, shrines and sacred source is a striking feature of the sanctuary (photo © 2007 Henri Ismail) |

Subsequently a few days

of fieldwork took place in and above the desa of

Rawabogo, Ciwidey, in the mountaineous region South West

of Bandung. Earlier this desa was the site of fieldwork

of Mr Henri Ismail, on the strength of which he obtained

an MA in political anthropology from Leiden University;

besides being an anthropologist, Mr Ismail is also a

talented professional photographer, and we are fortunate

that we could include some of his photographs in the

present webpage. Mr Ismail generously introduced Mr

Djunatan and his supervisor to this desa and especially

to the cultic lodge that is to form the focus of Mr

Djunatan's fieldwork. I wish to take this opportunity to

thank Mr Ismail for his inestimable contribution to Mr

Djunatan's project and (by his stimulating presence and

excellent photographing) to the success of this initial

field trip. In addition to Mr Ismail we were accompanied

by Mr Dayat, a university graduate from Bandung who in a

bid of finding his cultural identity became an adept of

the Nagara Padang cult, besides being a treasure of

information on the Sunda culture and its subdivisions.

Nagara Padang ('Valley State') or Gunung Padang

('Mountain State') are the general designations of the

extended mountain sanctuary upon which the cult focuses. In local cosmology and cult (distantly informed by ancient classical texts in the distinct Sunda language), the mountain tops constitute a sacred region conceived of as the spiritual capital of the mystical King and Queen of Sundaland -- which realm is metaphoric for the universe as a whole, and for the spiritual path of the human individual. The guardian of this sacred region operates an informal, family-based welcoming and training centre ('lodge', 'ashram') for pilgrims. He was our host and spiritual guide during three intensive days of pilgrimage, prayer, ritual, lengthy informal conversations and formal interviewing. The spiritual area is contested in various ways:

In three days and two nights the pilgrims make a collective spiritual journey, both in the mountains (where specific named spots, marked by the remnants of earlier offerings of incense, sigarettes, perfume etc, made a spiritual path graded into a number of trajectories separated by numbered gates -- with steps neatly hewn into the rock to facilitate the pilgrim's progress), and in the main assembly room and the sacrificial room of the lodge. Since the time of fieldwork was minimal, and since far more accomplished results on the basis of months of fieldwork will be incorporated in Mr Djunatan's thesis, I will not attempt to present a coherent picture here. Let me merely indicate a few striking aspects lest these may go lost in further analysis. The guardian's idiom was almost entirely in terms of the invisible, spiritual Sunda state of which the spectacular rock formation at the local crest of the west-east Java central mountain range were merely the bare skeletons. The general athmosphere of the spirituality thus mediated, far from being strikingly ancestral, local and animist (although there were those elements, too), was mainly reminiscent of a highly sophisticated form of Buddhism, in which great stress was laid on personal purity of intention, the spiritual realisation of personal destiny, and filial piety towards parents. Yet other idioms transpired, for instance most prayers were concluded with the standard Islamic prayer formulas of the Fatah and the Shahada, pronounced in mutilated Arabic; and frequently the names were recited of all the spiritual servants and demons considered to people the spiritual Sunda state as functionaries at various hierarchical levels. Thus we have an example of the syncretistic, layered Javanese religion so often described in the literature. Despite the guardian's emphatic discourse in terms of the pilgrim's personal responsibility for spiritual realisation and salvation, more mechanicistic, magical elements are also offered by the guardian: dust from one particular cave will protect the pilgrim's home, dust from another cave will yield great affluence, pressing one's thumb in an rock indenture called 'the fingerprint of the King' will yield royal strength, and special anointment and prayer at 'The King's Theater' will be particularly beneficial to artists, performers, photographers, poets, etc. Near the crest of the mountain, the most sacred spot of the trajectory (to be approached with bare feet only) consists of a very small platform (only 3 m2 area), surrounded by vertiginously steep and deep ravines on all sides, where the pilgrim is supposed to recline, his head resting against a round indenture in the rock, and (at the guardian's directions) to pray and receive colour visions indicative of his state of purity. In the nocturnal rites at the lodge, offerings in the form of fruits, sigarettes, perfume, and seven different liquids (tea, coco milk, black coffee, black coffee with sugar, etc.; the series used to include the local alcoholic drink (arak) but given the greatly increased dominance of Islam the spirits now seems to have resigned to non-alcoholic offerings. During the hours of prayer and offering, each of the pilgrims in turn becomes the focus of the guardian's attention. Then two complementary forms of divination are being used. Water is brought in a shining metal basin, in which rice peels are floating, each peel associated with a particular pilgrim. The guardian (and his father, who although having stepped down as active guardian isstill the true leader of the cult) prays in front of the pilgrim (who has his eyes closed), and the guardian somehow by the power of prayer and concentration manages to make the pilgrim raise his extended arms higher and higher, so that ultimately the upward pointing hands meet in a pious Javanese gesture of submissive greeting; on the basis of the guardians subsequent pronouncements (which were duly translated) I have the impression that the higher the arms are raised, the greater the guardian takes the pilgrim's intention and spiritual power to be. After opening his eyes, the pilgrim is then invited to pick his peel from the water, and the ease with which this is successfully executed seems to be an indication for the guardian as to the luck and blessing the pilgrim is to derive from his spiritual journey. Although the dominant idiom for the spiritual journey up the mountains is that of progress through the spiritual city of the King and Queen of Sundaland, other interpretations occasionally shimmer through -- but of course our minimum exploration was totally insufficient to get a coherent picture or to isolate genuine contradictions. The collecting of potent dust from some of the caves scarcely seems to tally with the idea of a spiritual city, and rather reminds one of a place inhabited by jinns in the Arabic / Islamic tradition (where of course the same idiom of a complex hierarchical state bureaucracy prevails, invisibly mirroring the tangible world of living humans, who inadvertently disturb and harm their invisible fellow-creatures, after which the latter may strike them with affliction). Near the First Gate there is a shallow cave where the rocks leave a narrow opening in such a way that a relatively slender adult with plenty of difficulty and care may twistingly squeeze himself through it downwards, head first, in emulation of a real birth. The act, for which some pilgrims volunteer, is supervised by the guardian and is interpreted by him in terms of the spiritual rebirth to be expected from the pilgrimage. However, rumours are also heard (but perhaps misunderstood) to the effect that this cave is the birth place, not just of individual pilgrim seeking spiritual renewal, but of humankind, animal life, and the entire world at large. I am inclined to take such rumours seriously, as an additional mythical layer adding to the complexity of Nagara Padang. Here at the same time an African parallel of this mountain sanctuary presents itself. For at various places all over the African continent (for instance the sanctuary of Fovu at Baham, Western Grassfield, Cameroon; at Kapiri Ntiwa, the famous High God shrine on the border between Malawi and Mozambique (Probst 2002); and a similar place has been reported to me in personal communication to exist in Uganda -- and probably a thorough search can identify more such places, perhaps including the Matopos Hills of South Western Zimbabwe) similar rock shrines can be found which are claimed to have been the particular place where the first animals and humans emerged from the earth to populate the world -- or where (in a later, vertical mythological dispensation) they were lowered onto earth from the sky. In all these cases we have to do with highly charged localities of great potency: exposed mountain crests (watersheds and natural noman's lands between domesticated human spaces) full of bare rocks which natural erosion has denuded of vegetation. In terms of my emerging 'aggregative diachronic model of world mythology' I see such sites as acting out the Narrative Complex 'The Earth as Primary', which appears to be associated with very ancient initiation cults (especially puberty rites) and which extensive comparative study has persuaded me to situate in Pandora's Box, i.e. in the mythological package with which some Anatomically Modern Humans left Africa 80 ka and again 60 ka BP; at the same time the association with mountain tops appeals to what I take to be a much more recent Narrative Complex, that of verticality (naked-eye astronomy, shamanism, and kingship). Extensive comparative study is needed before we can ascertain if the African cases cited, and possibly others to be revealed, are interrelated, what other cases may be found throughout the Old World (and possibly the New World), and what their distribution suggests as to the possible interrelation, and the direction of borrowing if any, between these African cases and those of Nagara Padang in West Java. |

Articulating the domesticated space in rural West Java and among the Nkoya of Zambia: The prevalence of reed/bamboo and the absence of chairs |

||

The traditional house the famous artist Sunaryo had built at his personal art centre in Bandung

A shelter near the entrance of the Gudung Padang sanctuary

The lodge of the Gunung Padang cult, i.e. the guardian's house. Note the motor cycle front left. The white flag is merely to chase birds and constitutes a typical feature of desa life

desa view; the climate and soil conditions are such that the fields are in continuous cultivation all around the year

Drying newly harvested rice on large tarpaulins in front of the lodge; the guardian (left) leisurely supervises the work. There are other signs of income differences which may well derive from the cult. Note that many of the desa houses are tile-roofed and, oin deviation from what I take to be the traditional pattern, lack bamboo walls. |

Around the lodge, bamboo structures prevail: roof, chicken run, bathroom, goat pen

the kitchen is the women's domain; they can only enter the assembly room to bring food

desa view

desa view; note the power lines both left and centre |

The ecology and economy of West Java

(paddy rice cultivation in irrigated, often terraced

fields in a mountaineous, volcanic area) are very

different from those of the Nkoya people of western

Zambia, among whom I have conducted fieldwork since 1972

and who are my standard reference for Sunda influence on

the African mainland. The Nkoya inhabit the well-watered,

fairly level plateau that constitutes the Zambezi / Kafue

watershed, and they cultivate millet, kaffirkorn, maize,

cassava and various other tubers on dry gardens cut out

from the rather dense savannah forest. Anthropologists

have long ago recognised (e.g. Redfield and Foster,

writing in the middle of the 20th century) that peasant

societies have many traits in common the world over, so

one would not be surprised to see parallels between

village life among the Nkoya and the Sunda people of West

Java, or such other peasant societies I have done

extensive fieldwork in, such as the Manjaks of Guinea

Bissau (West Africa), the Kalanga and Tswana of North

East Botswana, and the Khumiri of North Western Tunisia. However, in two ways the Sunda village seems to cast a remarkable light on life among the Nkoya, especially the Nkoya royal courts.

Thus, in the context of the Nagara Padang field trip Wim van Binsbergen could continue, albeit in the most superficial and invalid form of ephemeral ethnographic exploration, the search for possible Africa-related models, connections and continuities, that had also been the focus of the Sunda seminar a few days earlier; here it was an advantage that during his BA and MA studies at Amsterdam University in the 1960s, under Professor Wim Wertheim, Wim van Binsbergen had specialised in South East Asian studies, prior to joining the University of Zambia and effectively becoming an Africanist. |

On to Central Java |

||

This search for African

Sunda connections was subsequently extended to Central

Java, where the Yokyakarta region presents

|

||

Borobudur |

||

visitors approach the complex

One of the protruding lingams casts a shadow on one of the thousand exquisite reliefs

Approaching the top

The countless images of Buddha fortify the pilgrim on his or her way to the spiritual top

Many of the Buddha statues are so movingly beautiful that one does not know which picture of include and which to omit

Elephants, baldaquins, manigificent women. kings sitting in state on high thrones and nobles respectfully keeping to the ground -- images of ancient court life |

Most visitors are young Indonesians, and without inhibitions they appropriate the place for sacular purposes. The central girl sits on the central, massive stupa, which is surrounded by 72 hollow stupas with ajour stonework, thorugh which the inside Buddha statues can be seen and touched

Borobodur is not only a sacred site of Buddhism. From the top one has a view to the Roman Catholic complex where the first converts were made and the Virgin Mary is said to have appeared

Sages and boddhisatvas, kings, demons and gods cucceed each other in dazzling complexity on all sides of the seven circles to the top. The Borobudur is the detailed pictorial representation of several sacred books of Buddhism.

In the gate temple which, at considerable distance of the Borobudur itself, marks the beginning of the pilgrim's trajectory, Avalokitashvara features at the central Buddha's right hand, and receives offerings in his own right. In East Asia, he changed gender and became Kuan Yin, the goddess of mercy.

In addition to a much reproduced depiction of a Javanese ship mooring near Minangkabau-type housing, Borobudur has at least one other; no Sunda theory without going into the details of nautical skills of the ancient Indonesians

White aquatic birds, especially swans, geese and ducks, are signs of the primal creator god (or goddess, rather) throughout Eurasia, and (according to my comparative mythological reconstructions) have held that honourable position for perhaps 30 ka, right up to the Graeco-Roman Antiquity and Ancient India. On this relief, a goose is carried in procession on a ceremonial wagon

More white aquatic birds |

Two representations from Borobodur

feature prominently in the literature on Sunda-Africa

relations

Attempts at identification of these among the more than 1,000 Borobudur reliefs took an entire day, and was only partly successful (we failed to identify the musical relief in question, but instead spotted another similar one), but revealed new details of considerable interest. |

Prambanan |

||

|

|

This Hinduist complex of temples, the most compelling site of earlier phases in the multilayered religious influences that make up Indonesian cosmology, inspired the great Marxist and anti-Eurocentrist Dutch historian to his argument -- in the book In de ban van Prambanan (1954) -- on the Asia-based Standard World Model of historical development, with Europe not as standard but as deviation. |

Preliminary comparative lessons from the kraton (royal palace) of Yokyakarta, Central Java |

||

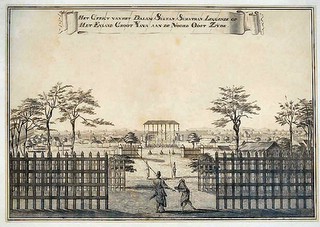

The Yokyakarta kraton in the late 18th century

The famous marble floor

One of the kraton's gamelan ensembles

A Sunda gamelan ensemble (source: http://www.cite-musique.fr/gamelan/pageph/ph102.html)

The West Java gamelan ensemble of the University College London, United Kingdom; not the xylophones, which apart from their heavily decorated supports are hardly to be distinguished from African counterparts (© Olivier Koechlin; source Basset 1995) |

Details of pillars

Dais

The Sultan's heraldic signs

One of the earliest depictions of a king's orchestra, kingdom of the Lower Kongo, Africa: Ezio Bassani, Un Cappuccino nell Africa (1670); source: http://negroartist.com/precolonial%20africa/index.html NB: pictures of royal musical instruments of the Nkoya people of Zambia may be found elsewhere in the present website |

Once in the mood to see intercontinental

correspondences and connections, one might easily jump to

unwarranted conclusions. Even a fieldtrip to Indonesia of

minimum duration, like the present one, already helps to

formulate some of the central methodological and

theoretical question involved. Is mere similarity, proof

of historical connection? How superficial or how profound

is the similarity? Suppose the similarity is indicative

of genuine historical connection, how can one begin to

assess its nature: from A (Africa) to B (Indonesia) -- or

from B to A (which I favour, and which is in line with

Oppenheimer's Sunda thesis, with the peopling of

Madagascar, and with the general spread of mytochondrial

DNA Type B from South EastAsia), or (in general the most

convincing alternative when genuine historical

connections are involved) do A and B both derive their

similarities from a hitherto unidentified common

historical source, C? Whatever the correct answers, far

more fieldwork and library research will have to be done

before meaningful and methodologically grounded

conclusions can be attempted. Meanwhile we may admit that the kraton (royal court) of the Sultan of Yokyakarta is a place where a Nkoya royal from Zambia, South Central Africa (and I am one, by adoption) can feel remarkably at home. This effect results from a number of specific features, which I will now provisionally outline; Nkoya royal capitals have been described in several of my own publications including Tears of Rain (1992), while there is an extensive scholarly literature on the Yogyakarta kraton and its counterparts elsewhere in Java. Like the Nkoya royal capital (lukena, whose noun-class prefix lu- marks the word as belonging to the class of royal things), the kraton occupies a rectangular area surrounded by a fence. Until today, zinkena (plural of lukena; z- pronounced as English th-) have a high reed fence (lilapa), supported by pointed poles; only royals (mwene, plural myene) have the right to display pointed poles. The kraton fence today is make in stone, and fortified; however, even in a first interview information was volunteered about the kraton fence having originally been in bamboo, with pointed poles, and the 18th-century print reproduced here (source) confirms this. Zinkena and their malapa have invariably connotations of human foundation sacrifices, and this regrettable custom does have Indonesian parallels (Wessing & Jordaan 1997) although I do not yet know to what extent these parallels also involve the kraton of Yokyakarta in the two and a half centuries of its existence. Since early colonial times, the principal lukena building ('palace', although usually without any of the splendour usually associated with that term) has been made out in brick, and it never occurred to me to ask whether before that time they were the usual pole and dagga of commoners' dwellings, or executed in reed in preservation of some ancestral model that might well have Sunda connotations. (There is an Ancient Egyptian parallel here: the most ancient, predynastic and early dynastic temples and royal dwellings were executed in reed -- which was abundant in the Nile valley and the Delta anyway --, and later Old Kingdom stone architecture retains the unmistakable signs of emulating such ancestral reed patterns in stone. The Dutch pioneer archaeologist Holwerda even claimed that this pattern extended all the way up north to the Netherlands, which he took as evidence as Neolithic immigration from the Fertile Crescent. Given the high incidence of Sumerian / Mesopotamian traits in predynastic and early dynastic Egypt, and the prevalence of reed architecture in Southern Mesopotamia to this very day, we might be included to trace the reed complex to Mesopotamia, but it might be Sunda related even there.) The kraton has a symmetrical orientation along a North-South axis, another parallel with the Nkoya lukena. The division in a public part accessible to commoners and strangers, and a secluded part reserved for the king and his courtiers, is a predictable feature of both kraton and lukena. Two types of kraton structures stand out for their Nkoya parallels:

Another parallel concerns the prominent role of the Prime Minister (Nkoya: Mwanashihemi), whose installation and seat of office is given great emphasis in both cases, and who is in fact the intermediary through which the king speaks with his subjects, adjudicates court cases, etc. Finally the kraton is the scene of several calendar festivals, in which royal power and blessing is reinforced, the bond between king and subjects is renewed, and (in a festival named after the Islamic confession of faith, Shahada) their adherence to Islam affirmed. There is a distant parallel here with the Nkoya Kazanga festival and with the principal Ancient Egyptian festival (heb sed). All these parallels can only have heuristic meaning, towards further research. I am not in the least suggesting that any underlying royal model manifested in latterday Nkoya royal institutions may have been directly borrowed from Java let alone from Yokyakarta. The time scale would also militate against this, for the Yokyakarta court only dates from the mid-18th century CE and therefore is not older that the major Nkoya royal dynasties (specific Nkoya physical courts are much younger, for contrary to the Indonesian custom Nkoya royals have moved the location of their courts by scores of kilometers at every royal succession). There is the theoretical possibility that the overall direction of historical indebtedness is not east-west but west-east, with African models penetrating South East Asia -- but (contrary to the Afrocentrist Clyde Winters) I consider this implausible, especially in the face of Madagascar cultural history, where the Sunda element is overwhelming and testifies of a massive east-west movement; also see the recent work by Dick-Read 2005. We would have to engage in a comparative study of ideas, institutions and implicit structures of royalty, not only on Java but throughout the Indonesian archipelago, and even throughout East, South East, and South Asia (Hinduism, Buddhist and Islam having been a major influence on Indonesia and having been especially mediated via the royal courts) before we are getting anywhere near a position where we can pinpoint, in time and space, the specific Asian antecedents of Nkoya court life -- yet that there are such antecedents seems undeniable to me. That in Nkoya kingship, in the furthest interior of South Central Africa where local literacy only penetrated in the 1910s, we have to do with the offshoot of some elaborate, literate tradition of dynastic statehood is suggested by something that has puzzled me from my first acquaintance with extensive, written accounts of Nkoya royal traditions (1977): the fact that, at least in the hands of literate Nkoya traditionalists of the mid-20th century, the full list of all incumbents of the few major Nkoya dynasties is known, and that these incumbents are numbered consecutively, starting at one and continuing to more than a dozen. For decades I have believed that this strange phenomenon for an illiterate society was due to influence from the bible (the Nkoya traditionalists in question were bible translators) or from primary school history books. Now I believe that influence from Asian (probably Indonesian) state systems must have been an additional factor, if not the only factor. |

The Queen of the South |

||

Sea sand covers the kraton ground |

At the kraton we are confronted with a

cosmological feature which is remarkable, and not only

because it is suggestive of Western Zambian parallels.

The Sultan is supposed to have a spiritual marriage with

the Queen of the South, who is in fact the goddess of the

sea. The nearest sea coast c. 60 km to the south. Yet

apart from the paved sections of the kraton (with marble

tiles), the ground area of the kraton is covered with sea

sand, brought across that distance. The Queen of the

South is not only a concept particular to Yogyakarta, but

reverberates in popular cosmology throughout Java. It

emerged in the desa-based syncretistic cosmology of the

keeper of the shrine complex of Nagara Padang. It also

emerged in the conversation of members of the

intellectual elite of Bandung city, when a chain of

highly disturbing occult recent events in their

neighbours' house, was reticently addressed by an

increasing number of local syncretistic spirit mediums,

in whose midst finally the presence and voice of the

Queen of the South was manifested, as the omniscient

supreme ruler of evil spirits and sorcerers. (I say

reticently, for in fact, this and other similar accounts

showed an almost tender care for the afflicting invisible

agents, who yet (like New Testament demons or Arab jinn)

kept coming back and proliferating, and who were

sufficiently respected as fellow creatures and as owners

of the place never to be confronted with the kind of

drastic violent eradication measures African medicine has

in stock for their African equivalents). The above suggests that in Java the Queen of the South is a more or less demonised transformation of a very ancient and widespread (Upper Palaeolithic Eurasia, according to my intercontinental reconstructions in comparative mythology -- and even before the installation of verticality as the central idiom of shamanism and kingship) of the Mistress of the Primal Waters, who produces, as the truly cosmogonic moment, the Land as her son; the latter subsequently becomes her lover and together with her brings forth the whole of the visible world. The union of Sultan and Queen of the South re-lives this ancient cosmological asymmetrical complementarity between the Land as junior and the Sea as senior. It is quite conceivable that the cult of the sea goddess in West African voodoo, Mami Wata, etc. is a Sunda trait originating in the particular for this widespread and ancient cosmological theme took in SE Asia. But such a claim would be very difficult to substantiate, for, being ancient and widespread, it would have reached Africa along different paths, and might even be claimed to be originally African, perhaps even part of the original cultural and mythological package ('Pandora's Box', I have called it) with Anatomically Modern Humans left Africa c. 80 and c. 60 ka BP. Meanwhile the idea of the King being paired to a Queen of the South has a literal parallel, not so much among the Nkoya (although there are relevant elements in the typically female kingship of Shakalongo, in the South of Nkoyaland) but among the Luyi / Barotse / Lozi , where the Queen of the South (Mulena Mukwae) outside the floodplain in the Southern part of the Lozi territory is a recognised royal office in its own right, to be filled by the Lozi king's classificatory 'sister', and complementary to that of the Litunga (literally, 'Land') whose capital is in the northern part of territory, at the edge of the floodplain. The title Litunga is of local, Nkoya i.e. South Central Bantu origin; Nkoya is virtually indistinguishable from the Lozi court language Luyana, but very different from the Southern Bantu Lozi language which has prevailed in the floodplain since the early 19th century, and which was brought by the Kololo on the wings of mfecane. Quite possibly, the standard explanation for the Litunga title ('that the king is owner of all the Lozi land', Gluckman in various publications) is rationalisation, whereas in fact the explanation of the term may be mythical, referring to the very ancient Land/Sea dichotomy. If the latter is the case, than we detect here the same seniority of the King's Sister ('Sea') over the junior position the king himself occupies as 'Land', which we also find in many aspects of the Nkoya kingship. |

|

The vicissitudes of male and female genital mutilation (circumcision) in Indonesia and Zambia, and possible Sunda connotations |

||

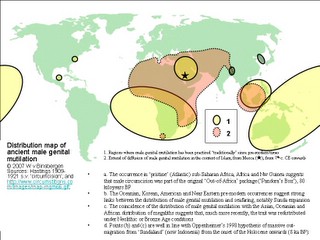

World distribution map of male genital mutilation (click to enlarge) World distribution map of female genital mutilation (click to enlarge) A map of Java and the periodisation of the penetration of world religions (source: Basset 1995); click to enlarge |

One of the interesting findings at the

Yogyakarta kraton is that not only royal princes are

being circumcised (like all Muslim boys, in remembrance

of Ibrahim's / Abraham's thwarted human sacrifice of his

son -- Ismail or, by the Judaeo-Christian tradition,

Ishaq / Isaak), in a ritual called khitanan, but

also royal princesses. By our report the latter rite (tetesan)

is locally performed at a tender age (2-3 years according

to our informant (an official kraton guide and son of the

Keeper of Royal Daggers / Keris ), 5-8 years

according to Wiryono n.d.: 11), and is limited to

smearing the girl's vulva with powdered turmeric (kunjit).

The latter could be a replacement of yellow ochre, which

(along with the red variant) has been used to mark the

sacred in many cultures since Middle Palaeolithic times.

Other sources on Central Java confirm the age data and

the role of turmeric, and reveal that female

circumcision, under whatever specific form (sometimes

involving piercing the clitoris with a needle) is not a

royal, but a general custom, throughout Indonesia (cf.

USAID 2004; Moore & Rompies 2004). I had already identified male genital mutilation as a possible Sunda-related trait, and drawn a map of its world distribution which seems to confirm this possibility -- although over-land westbound diffusion from a Central Asian or South East Asian source in the context of the 'Back into Africa' migration seems equally likely. Now I have to consider whether also female genital mutilation could be Sunda related, and could also be equally explained by the over-land alternative. The distribution map to the left gives the basic data. In the specific case of the Nkoya people of Zambia (whom I take as a typical case of Sunda influence on the African continent), it is remarkable that their royals up to the early 20th century CE engaged in male genital mutilation, and that the independence of their kingships from the empire of Mwatiyavwa ('Lord of Death') in Southern Congo has been associated, in local traditions, with the rejection of such circumcision (cf. my Tears of Rain (1992), and: Van Binsbergen, W.M.J., 1993f, ‘Mukanda: Towards a history of circumcision rites in western Zambia, 18th-20th century’, in: J.-P. Chrétien, avec collaboration de C.-H.Perrot, G. Prunier & D. Raison-Jourde, eds, L’invention religieuse en Afrique: Histoire et religion en Afrique noire, Paris: Agence de Culture et de Coopération Technique/Karthala, pp. 49-103). The predilection for circumcision these royals share with the royal and priestly classes of Ancient Egypt especially in Old Kingdom times, but rather than seeing this parallel as evidence of direct Egyptian influence on the Nkoya, I would read this as suggestive of a common substratum, which may or may not contain Sunda elements. The (apparently) standardised Islamic form of male genital mutilation in Indonesia, and the relatively mild and harmless form of female genital mutilation there, make it rather difficult to see these Indonesian practices in their present-day form as the possible origin of the much more intrusive and harmful forms of female genital mutilation especially in Africa. Moreover there are problems of periodisation: although Oppenheimer proposes a westbound Sunda expansion from the very onset of the Holocene (10 ka BP), in actual fact the historical, comparative ethnographic and protohistorical attestations of such westbound expansion, especially in Africa (including Madagascar), hail from a much more recent past, 2 to 3 ka BP or more recently (cf. Dick-Read 2005). Yet is seems possible that in this more recent period, Sunda expansion has been instrumental in spreading Indonesian forms of male circumcision especially to South Central Africa (Congo, Zambia). These relatively southerly areas, while in or near the path of the Mozambican/Angolan corridor which I have identified (by a combination of genetic markers and comparative ethnographic indicators) as a Sunda concentration area on African soil, are not contiguous with the concentration areas of incision and infibulation of major African forms of female genital mutilation. Since the world distribution map of female genital mutilation provisionally indicates that in South East Asia female genital mutilation is specifically associated with the spread of Islam (a phenomenon confined, in that region, to the last millennium), in general a Sunda effect on the world distribution of female genital mutilation seems unlikely. But suppose Islamic tendencies towards female genital mutilation merely reinforced, in South East Asia, far older related practices? Then Sunda would be back in the race. Some of the other genetic markers indicative of Sunda influence do suggest a second east-west Sunda corridor across the African interior, and this would largely coincide with the concentration areas of incision and infibulation, as well as with the postulated Urheimat Bantuist linguists have suggested for proto-Bantu -- in which I prefer to detect (reviving the ostracised Trombetti scenario of the 1920s; cf. the recent Pedersen n.d.) considerable Austric i.e. Sunda influence, including the word ba-ntu itself, cf. taw. Thus we are perhaps brought to hypothesise, in addition to

However, wave (2) is virtually indistinguishable from a a model that is preferable on systematic grounds: the model of an over-land westbound movement from Central Asia 'Back into Africa', via West Asia and skirting Europe. Much further research and reflection are required before we can adopt a definite position in this matter. Interestingly, it is a widespread belief among the Sundanese speaking Muslims of West Java that circumcision (and even Islam in general) originate from Sundaland and only from there reached the Arabian peninsula. I am not surprised by such localising, which could be entirely mythical. It is quite common in popular religion. For instance, in Islam, the peasants of the highlands of North Western Tunisia would associate specific places in their local landscape with the Prophet Muhammad as if he, like their local saints, had travelled there so that wherever he had spent the night a shrine had to be made -- and where, like in the Yokyakarta kraton, a specific mountain slope is called by the name of the Muslim confession of faith, the Shahada; and similar tendencies may be seen in popular Christianity on the northern side of the Mediterranean. However, we cannot totally rule out the possibility that there is some historical truth in the claim that male genital mutilation is a pre-Islamic local trait in Java. |

|

Indonesian avant-garde modern art |

||

A characteristic installation by Sunaryo: Masa Lalu Masa Lupa #3 (source)

|

|

Finally, back in Bandung, the post-modernr philosopher and aestheticist Professor Sugiharto (whose book on the most celebrated Indonesian painter and sculptor Sunaryo had just come off the press) shared his great knowledge and love of modern avant-garde Indonesian art of world class, notably of the personal museums of Sunaryo and Nyoman Nuarta. The pictures to the left present some Sunaryo's most famous works, from his personal museum; the right to circulate these pictures remains © 2007 Sunaryo. |

return to current Topicalities page | return to Shikanda portal

click

the image to return |

||||

|

|

|